Zeynep Sümer via Unsplash

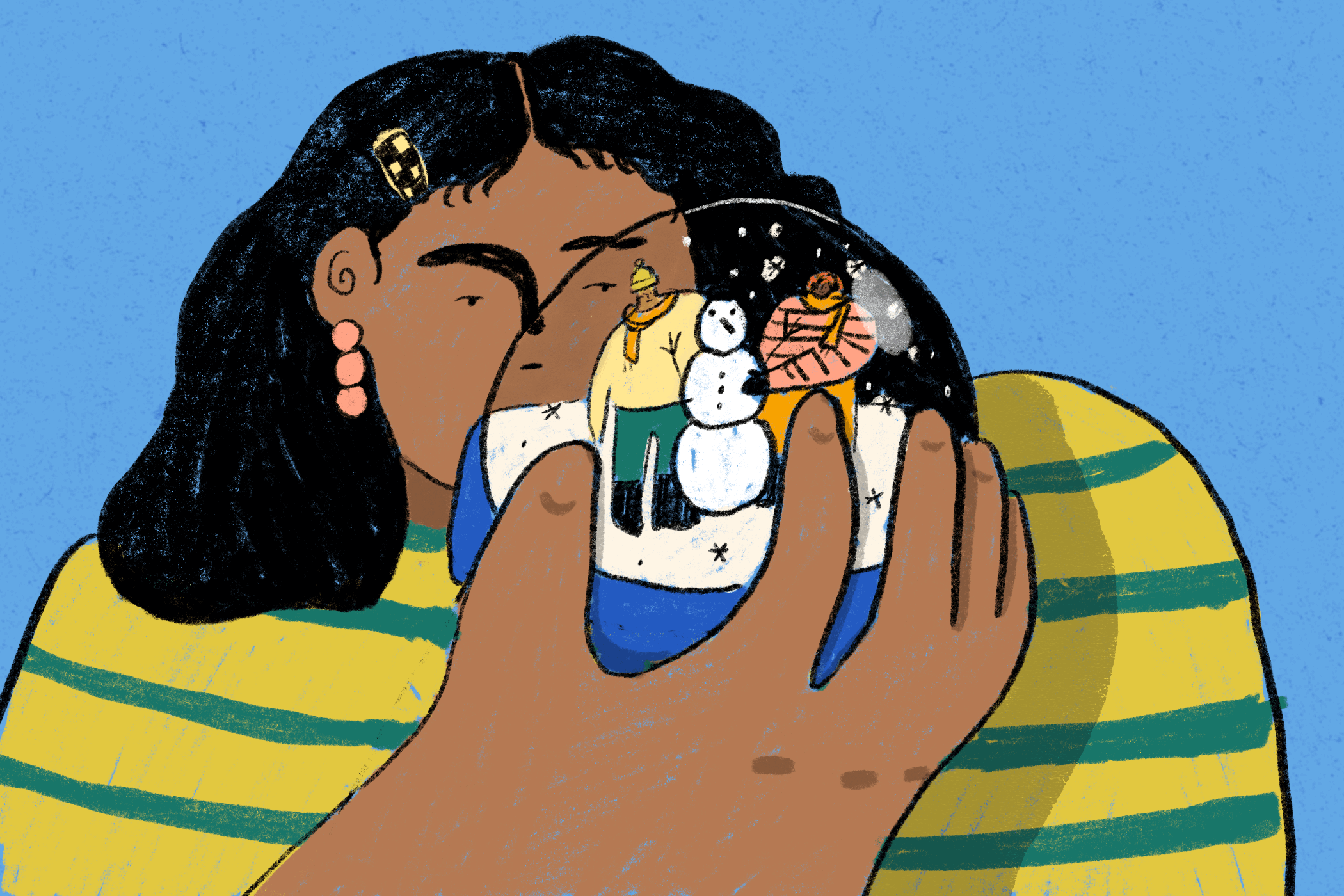

Home for the holidays: celebrating Ethiopian and American festive traditions

As the festive season approaches, author Meron Hadero reflects on her family’s traditions that follow both Ethiopian and American calendars.

Meron Hadero

21 Dec 2022

My debut short story collection, A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times, has just been released in the UK in the midst of the holiday season, and I can’t help but reflect on this timing. The title itself suggests inviting gatherings and the comfort of a home cooked dinner, evoking the spirit of holidays – a time where hearth and heart are a little more open, a time for reaching out to welcome friends, family and even strangers. It’s a season for coming together to reinforce, reestablish, reform and transform traditions often around a dinner table warm with food and love.

I was born in Addis Ababa and came to the US as a young child, and so I’m moved to recall some experiences of my own in the US where Ethiopian traditions and American ones met. Even if they didn’t perfectly overlap, both of these cultures commingled in beautiful ways and the appreciation of each was enriched by that exchange. Such interactions are at the heart of my story collection, which features characters who are immigrants, refugees and those facing displacement – all people navigating new cultures as they try to find a sense of security in unfamiliar geographies, striving for a feeling of belonging and a place that they each can call home.

“Holiday rituals punctuate a year, ground time itself and help us measure – emotionally, not just logically – time’s passage”

That process of finding and building home is captured in the creation and recreation of traditions: these rhythms set the course of a day or a year or a life, and are a certain kind of timekeeping in themselves. Holiday rituals punctuate a year, ground time itself and help us measure – emotionally, not just logically – time’s passage, what the past has built and what the future might promise.

Of course no holiday marks time better than New Year’s Day, which in Ethiopia is 11 September, falling several months before we celebrate it in the US. The Ethiopian year itself falls seven to eight behind, too. Timelines repeat; September of 2007 on the US calendar was the Millennium in Ethiopia when American superstars – including Beyoncé herself – performed in Addis Ababa to highlight the national milestone.

For me, Ethiopian New Year rituals are simple and private. Last year on 11 September, I scrolled through old “out of date” New Year’s GIFs to send family. This past September, I simply called to wish relatives a happy 2015.

“Celebration is in the act of gathering and eating together. That is what a holiday is about”

After Ethiopian New Year, the holiday season moves on to Thanksgiving, and while there’s no equivalent per se in Ethiopia, its holidays often resemble this one. There aren’t gifts exchanged, no trees put up, no eggs dyed, no candy collected door-to-door. Celebration is in the act of gathering and eating together. That is what a holiday is about. Sharing a meal and making a meal are acts of love. I once asked an aunt how she prepared her wonderful wot, and she told me, “First, chop 60 onions.” I couldn’t believe it. “60? Six zero?” I asked. I must not have heard that right, but she confirmed: “60. Six zero.”

Surely she used a food processor, I thought, but no, 60 onions chopped by hand. That is a gift. There is no need for anyone to add to the presents under the tree or wrap any store-bought trinkets as a gesture of care. This was care. Not just a gesture of care but the very essence of caring itself. I never did try to make her recipe, though one year with my mother I sought out some short cuts, using a slow cooker to simmer just several onions with a little garlic. That was the year I learned soggy garlic turns everything green, as if to prove that time is an essential element in the kitchen for these national dishes and you can’t skip ahead, with cooking as well as with calendars.

Thanksgiving must have felt like such a familiar holiday to our recently arrived family who would come to eat all day long. We’d set out a mix of customary American foods alongside Ethiopian favourites. By the end of the meal, the American dishes were largely untouched, just seemingly for display, while the Ethiopian foods were gone first and in a hurry. My mother never stopped making turkeys or setting out stuffing, even when Thanksgiving overlapped with a fasting season when only vegan foods are consumed by those observing.

“I can’t help but wonder how many dining tables were like ours, and if others had gone even further in the blending of cultures”

Eventually, my extended family came to enjoy the mix of foods as traditions merged and complemented one another. New compromises solved cultural impasses: vegan pumpkin pie was discovered, set out alongside vegan stuffing and vegan potatoes in years when a fast encroached on Thanksgiving day. Turkey became an expected staple, even if some years it was mostly frozen until the fast broke. We found a way to make it work and I can’t help but wonder how many dining tables were like ours, and if others had gone even further in the blending of cultures – maybe turkey wot, perhaps an injera-based stuffing, berbere yams?

Finally, the winter holidays end with Ethiopian Christmas, which is on 7 January while in the US, it’s 25 December. This second chance to mark the holiday means wishes are made twice and gatherings may repeat. It’s another opportunity to experience the hospitality of the holidays and a way to extend that source of warmth into the winter. While these practices shift over time, including during the Covid-19 pandemic, something carries on across borders, through challenge and change, year after year as customs adapt and slowly settle into place forming the foundations of home.

Meron Hadero’s debut short story collection, A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times, is out now, published by Canongate.

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.