Canva

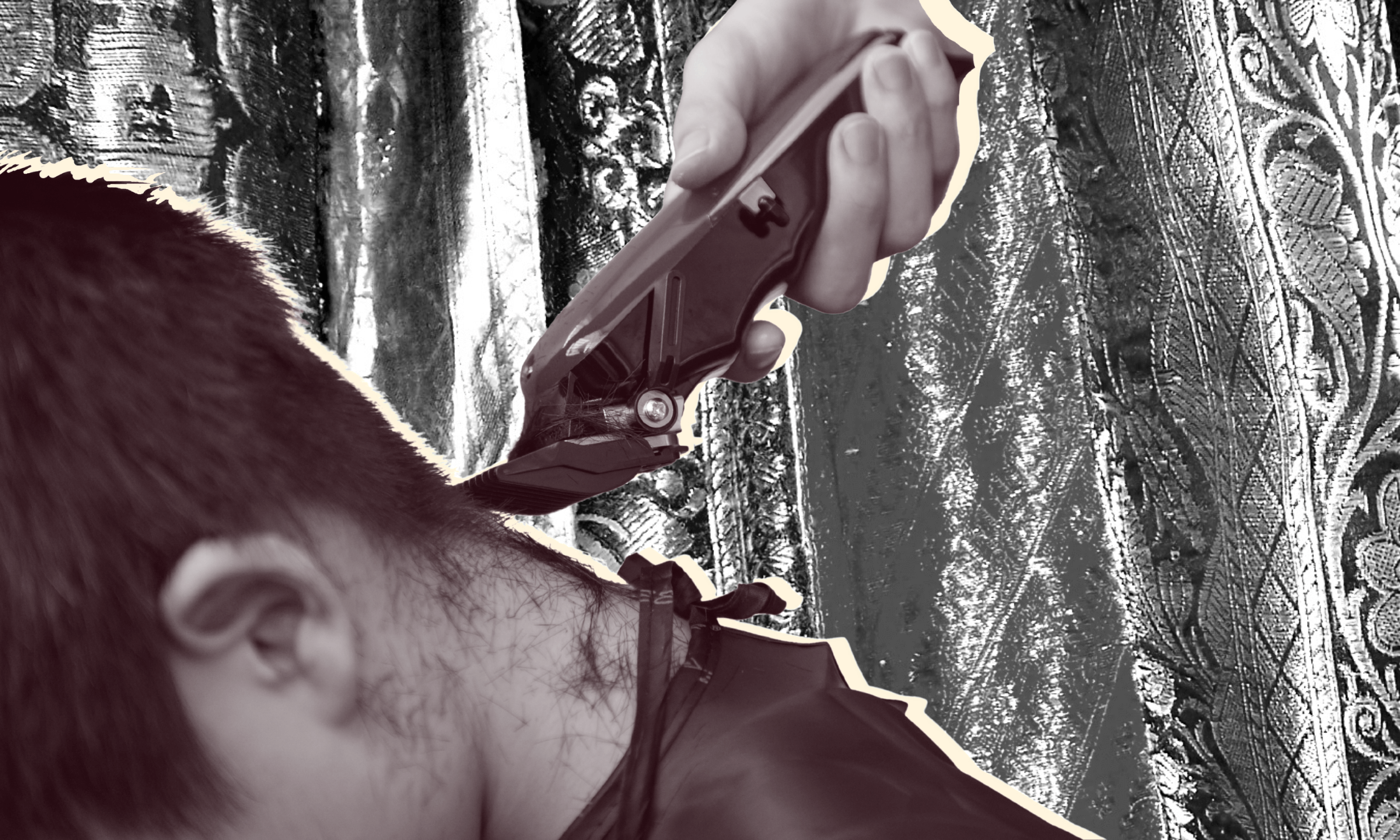

How shaving off my hair made me renavigate my South Asian identity

In the safety of lockdown, I was finally able to shave my hair without worrying about what my aunties would say on WhatsApp.

Mina Singh and Editors

07 Dec 2021

I’ve always felt like having beautiful, long hair was the defining aspect of South Asian femininity. Growing up, I remember being mesmerised by the Vatika hair oil adverts that came on between my mum’s serials; women with hair so thick and glossy it looked like CGI in a 1990s film would strut across the screen and into the embrace of a womanhood so perfect, I could barely imagine it for myself. And with my background being Sikh, hair is everything. Beyond signifying beauty and conventional womanhood, keeping your hair uncut is an act of respect for the perfection of God’s creation.

Although most of my immediate family has cut their hair since my grandparents moved to the UK in the 1960s, I’d always been spellbound by the women with thick braids hanging down their backs at my gurdwara, swaying as they walked through the prayer hall.

That admiration had, however, always been coupled with a knotted discomfort in the pit of my stomach. My gurdwara was frequently used for weddings and the congregation was divided by gender (women on the left, men on the right). Navigating such a heavily gendered and heteronormative space as a closeted lesbian was uncomfortable, to say the least. Since I looked like everyone else in the prayer hall, though, the weird, secret queasiness I felt rising in my chest was just that: secret.

“With my background being Sikh, hair is everything”

Earlier on this year, I ended up shaving my head. I had never planned to; I was in the midst of a health crisis which meant my hair had started falling out, and finding clumps of it in the shower and on my pillow was too much for me, especially since I’d always been complimented on how thick and healthy my hair had been. There are very few circumstances where the average South Asian woman would cut off all their hair – the only time I can think of hearing about it as a child were stories of upper-caste Hindu women being pressured by their communities into shaving their heads when they became widows.

Although I spent ages playing it off as something casual to my non-Sikh friends, taking on the look of queer icons like Lena Waithe, Kristen Stewart, Reeta Loi and Amandla Stenberg and therefore suddenly becoming much more visibly queer myself has been a much bigger deal than I think I’m willing to properly admit. Shaving your head means relinquishing your femininity and looking towards androgyny, even butchness. I’m thinking of Grace Jones writing in her memoirs about how buzzing her hair off made her ‘look more abstract […] woman, but not woman,’ and the cover of Leslie Feinberg’s Stone Butch Blues.

“Shaving your head means relinquishing your femininity and looking towards androgyny, even butchness”

I’m lucky that no one’s explicitly barred me from doing so, but that queasy shame I can’t get rid of means I haven’t dared to step anywhere near a gurdwara since I shaved my head. As I mentioned, most of my family have cut their hair, but in doing so they’ve generally kept within Western parameters of what’s considered ‘acceptable’ on the basis of your gender. The few bits of my family I have seen since the big chop haven’t really commented on it, or at least not to my face. As much as I might claim not to care, I’m not immune to the unspoken – or whispered – question of why I have such short hair as a South Asian woman. Questions like whether my parents have let me get too Westernised, if moving away for uni has turned me too modern, if I’m a lesbian.

Strangely enough, the pandemic and being away from home has definitely helped me to process the big chop. Being at home and in lockdown for a few months after I’d shaved my head meant I wasn’t at the gurdwara or visiting parts of my extended family. Now living away at uni means I feel like I can exist as a queer person in public without having to worry about if one of my aunties is going to spot me on the bus and start off the Whatsapp brigade.

“Though I have cut my hair and felt pangs of shame and panic as a result, I also feel nostalgic for how my longer hair connected me to my Punjabi heritage”

It’s strange – though I have cut my hair and felt pangs of shame and panic as a result, I also feel nostalgic for how my longer hair connected me to my Punjabi heritage. Not just the shiny adverts for beauty products, but of my memories of being seven years old and sitting down between my mum’s knees whilst she oiled and plaited my hair, staining the collar of my pyjamas green in the process. I miss spending what felt like hours with pins in my hands, waiting whilst my mum tried to fix a parandi to my plait before a family function or wedding, which was definitely too short and thick for the hair ornament to blend in seamlessly. Detaching the weight of it from my head and getting to run my hands through my hair at the end of the night felt like a sweet release, almost as liberating as the first time I felt the smoothness of my scalp after buzzing my hair off.

Shaving my head and keeping my hair this short has definitely made me reassess my relationship with my culture and my identity, but I hope that shaving my head doesn’t necessarily translate to a complete cutting-off. I’m not sure if I’ll make it back to the gurdwara in the next few months; maybe taking the time to process how my spirituality and queerness can coexist in my own space first could make that step easier. I bought myself a bottle of Vatika hair oil and I rub it into my grown-out buzz now, even though the girl on the bottle looks nothing like me.