Arian Zwegers via Flickr

How the Aral Sea disaster created unrest in contemporary Uzbekistan

Behind violent protests in the autonomous region of Karakalpakstan is a history of festering social problems caused by the Aral Sea disaster.

Parvina Ayubova and Editors

24 Oct 2022

In July 2022, mass unrest erupted in the autonomous region of Karakalpakstan situated in Uzbekistan. Thousands of people went to the streets of Nukus, the republic’s main city, where the protest descended into bloodshed and chaos. According to officials, 18 people were killed, and more than 240 injured, including law enforcement officers. The unrest was a direct response to planned constitutional changes that would deprive Karakalpakstan of its autonomous status within Uzbekistan. After the protests, Uzbekistan’s president came to Nukus and promised that the legal status of Karakalpakstan wouldn’t change. The U-turn was welcomed, but tensions remain. This is because behind the protest is a history of festering social problems caused by the environmental destruction of the Aral Sea.

***

The first time I saw the Aral Sea – or what remained of what was once the fourth-largest inland lake in the world – was in 2018. The bone-dry landscape of the Ustyurt Plateau in northwestern Uzbekistan left me speechless. The vast stretches of ghostly white salt flats – strangely mesmeric in their lifelessness and absolutely unsuitable for farming – were a silent witness to one of the worst human-induced environmental disasters of the past century. What used to be a huge, thriving body of water with a diverse ecosystem has become a dead desert covered with sand and salt. The desiccation of the Aral Sea is a textbook example of human exploitation and destruction of natural resources.

The Aral Sea is a terminal lake, historically dependent on the inflow from its two rivers, the Syr Darya and the Amu Darya. For centuries, the lake was an oasis among the desert landscapes of an arid region. In the 1950s, the Aral Sea covered an area of over 66,000 square kilometres (half the size of England), with a total water volume of 1,070 cubic kilometres and a maximum depth of 66 metres.

“The desiccation of the Aral Sea is a textbook example of human exploitation and destruction of natural resources”

At the time, the sea actively supported farming and fisheries and was the main source of employment for local communities. However, things began to change when the Soviet regime decided to turn the Aral Sea basin into the cotton belt of the USSR. The water from the Syr Darya and the Amu Darya was diverted to feed numerous irrigation canals needed for the massive production of a thirsty cash crop, which was grown mainly in Uzbekistan.

This artificial cotton ‘paradise’ carried a death sentence for the Aral Sea. Since the early 1960s, the lake had been decreasing rapidly as the waters of its feeder rivers were used to irrigate cotton fields. Soviet experts predicted the shrinkage of the lake, but considered it a ‘worthwhile tradeoff’ in exchange for cotton. As a result of the Soviet agricultural mismanagement, the Aral Sea lost 90% of its original size in the next four decades and by the 1990s split into the North Aral Sea (found in modern-day Kazakhstan) and a two-part South Aral Sea, which lies within Karakalpakstan, an autonomous republic within Uzbekistan.

The catastrophic loss of water has led to a series of devastating climate and socio-economic consequences for the region. “The Aral Sea disaster had a severe impact on the local population at different levels – ecological, economical, health, cultural. People lost their sources of income; environmental degradation resulted in profoundly negative effects on human health,” says Rustam Murzakhanov of the Michael Succow Foundation, an expert on protected areas and biosphere reserves. As the lake quickly began losing its volume and area, the level of salinity in it increased, and the exposed seabed turned to a vast saline desert.

“As a result of the Soviet agricultural mismanagement, the Aral Sea lost 90% of its original size in the next four decades”

This artificial cotton ‘paradise’ carried a death sentence for the Aral Sea. Since the early 1960s, the lake had been decreasing rapidly as the waters of its feeder rivers were used to irrigate cotton fields. Soviet experts predicted the shrinkage of the lake, but considered it a ‘worthwhile tradeoff’ in exchange for cotton. As a result of the Soviet agricultural mismanagement, the Aral Sea lost 90% of its original size in the next four decades and by the 1990s split into the North Aral Sea (found in modern-day Kazakhstan) and a two-part South Aral Sea, which lies within Karakalpakstan, an autonomous republic within Uzbekistan.

Climate change has also exacerbated water scarcity. Since the beginning of the 20th century, Central Asia has already warmed at least 1 degree Celsius. The rise in temperature led to the melting of glaciers that fed the Syr Darya and the Amu Darya, thus helping to accelerate the drying of the Aral Sea. The lake’s shrinkage has contributed to the transformation of climate in the local vicinity: summers became hotter and winters colder. On average, summer temperatures on the dried territory have risen by 0.1 – 0.4C, while winter temperatures have decreased by 0.2-0.6C.

The region’s once prosperous fishing industry had evaporated along with the water leaving thousands unemployed, thus fuelling local poverty. Besides extremely high salination, the soil of the former lakebed was polluted with river sediments and toxic chemicals used by the Soviet planners to boost cotton production. Dust storms were frequent in the area and carried toxins over long distances, contaminating crops and drinking water and causing different respiratory diseases among local inhabitants. Karakalpakstan and the southern part of Kazakhstan had been affected the most.

“The water we drink, the earth we walk on, are all poisoned with chemicals”

Tulepbergen Kaipbergenov – a Karakalpak novelist

“The water we drink, the earth we walk on, are all poisoned with chemicals. People fall ill with hitherto unknown diseases and die. I feel especially sorry for children – they are our future,” wrote Tulepbergen Kaipbergenov, a Karakalpak novelist, in his literary essay in 1993. To date, up to 75 million tonnes of dust and chemicals are delivered from the Aral Sea annually. According to the UN Multi-Partner Trust Fund for the Aral Sea region, low fertility rates in Karakalpakstan and high mortality have slowed down population growth in the region.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, responsibility for tackling ecocide lay on the shoulders of Central Asian republics, which didn’t have the financial capacity to deal with the crisis after decades of exploitation and resource extraction by Moscow. In 1993, the five established republics formed the International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea but took no significant action except for the activities of various international organisations.

Oral Otaniyazova, a well-known Karakalpak obstetrician and researcher, complained that Uzbekistan wasn’t developing “any national programme to improve the health of the population or the environment”, in an interview with Index on Censorship back in 1998. Kazakhstan, in turn, with the help of the World Bank, built the eight-mile Kok-Aral Dam to reserve its part of the lake and soon saw an 18% increase in mass of the North Aral Sea. On the Uzbek side however, the South Aral Sea has continued to evaporate due to the low precipitation rate and further irrigation. By 2014, the eastern basin of the South Aral Sea had completely dried up for the first time in 600 years.

Since President Shavkat Mirziyoyev came to power in Uzbekistan in 2016, the government has revised its approach to mitigating the environmental disaster and intensified efforts to address the crisis. Two state development programmes were adopted over the last five years; one aimed at the Aral Sea region, and the other included the whole of Karakalpakstan. In 2021, the United Nations, at the initiative of the Uzbek side, declared the Aral Sea region a zone of ecological innovations and technologies. The resolution passed by the UN General Assembly called on all interested parties to take steps to overcome the consequences of the Aral Sea crisis.

Over the past two years, Tashkent (the capital of Uzbekistan) increased spending to improve infrastructure in the region. One of the projects widely covered in the media was the reopening of the airport in the former port town of Moynaq, situated on the southern shore of the Aral, after it had been closed for 30 years. “The Uzbek government does put a lot of effort into coping with the disaster on the national, regional and international level,” agrees Rustam Murzakhanov. “But, in many cases, it is dealing with symptoms, not causes.”

The combination of harsh climatic conditions and economic stagnation has put a heavy burden on Karakalpakstan and its 2 million people. Land degradation and deforestation, poverty, poor infrastructure, and increased health problems have made the region one of the most vulnerable and underdeveloped in Uzbekistan. For all these years, Karakalpaks had suffered silently until the region’s recent violent revolts.

“As the lake vanished, so did the welfare of the region. A thriving sea, croplands, plants and animals, and people, were all traded up for ‘white gold’”

“One of the triggers for the events in Karakalpakstan was the socio-economic situation there. The government of Uzbekistan, understanding the problems in this direction, sought to improve the economic situation in the republic,” says Akram Umarov, an independent researcher from Uzbekistan. However, despite significant funds allocated for the region’s development, Karakalpakstan remains one of the less developed territories of Uzbekistan, Umarov explains. “At the end of 2020, despite significant growth in recent years in terms of gross regional product per capita, Karakalpakstan is still 37% below the level of GDP per capita on a national scale. The official unemployment rate at the end of 2021 was 10.1%.”

The transformation of the Aral Sea into a toxic wasteland is a symbol not only of an anthropogenic environmental disaster, but of an economic and social one. As the lake vanished, so did the welfare of the region. A thriving sea, croplands, plants and animals, and people, were all traded up for ‘white gold’ (a common nickname for cotton) and then left on their own. The short-sighted exploitation of nature has shaped future social and political instability, with direct and indirect consequences seen throughout every aspect.

“Uzbekistan belongs to the countries with the highest sensitivity to climate change,” explains Rustam Murzakhanov. Water is now the key issue in light of climate change, and in the future, it will be even more serious. The current speed in the implementation of water-saving technologies is not sufficient for adaptation to climate change.” Among other important issues is the safeguarding of local biodiversity as it could help mitigate and adapt to climate change.

Today, Uzbekistan is far more active in addressing climate change challenges, including the Aral Sea disaster. At COP26, the country set an ambitious goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions per unit of GDP by 35% by 2030. The government also relies on increased use of renewable energy sources and plans to bring their share to 25% of total power generation.

However, addressing climate change on its own is not enough. There must be a willingness to learn from the past. The events in Nukus, at first glance, were triggered by the constitutional amendments. Yet in reality, they were the result of long-standing local grievances aggravated by the ecological problems coupled with inaction from authorities. The short-term solutions such as throwing money to quell the uprisings at any cost shouldn’t be a substitute for strong, long-term development that is ecologically sustainable and socially inclusive. With every year, the climate crisis chips away at Central Asia more and more. The fate of the Aral Sea is a bitter reminder of why we need to learn from our mistakes. Will we?

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

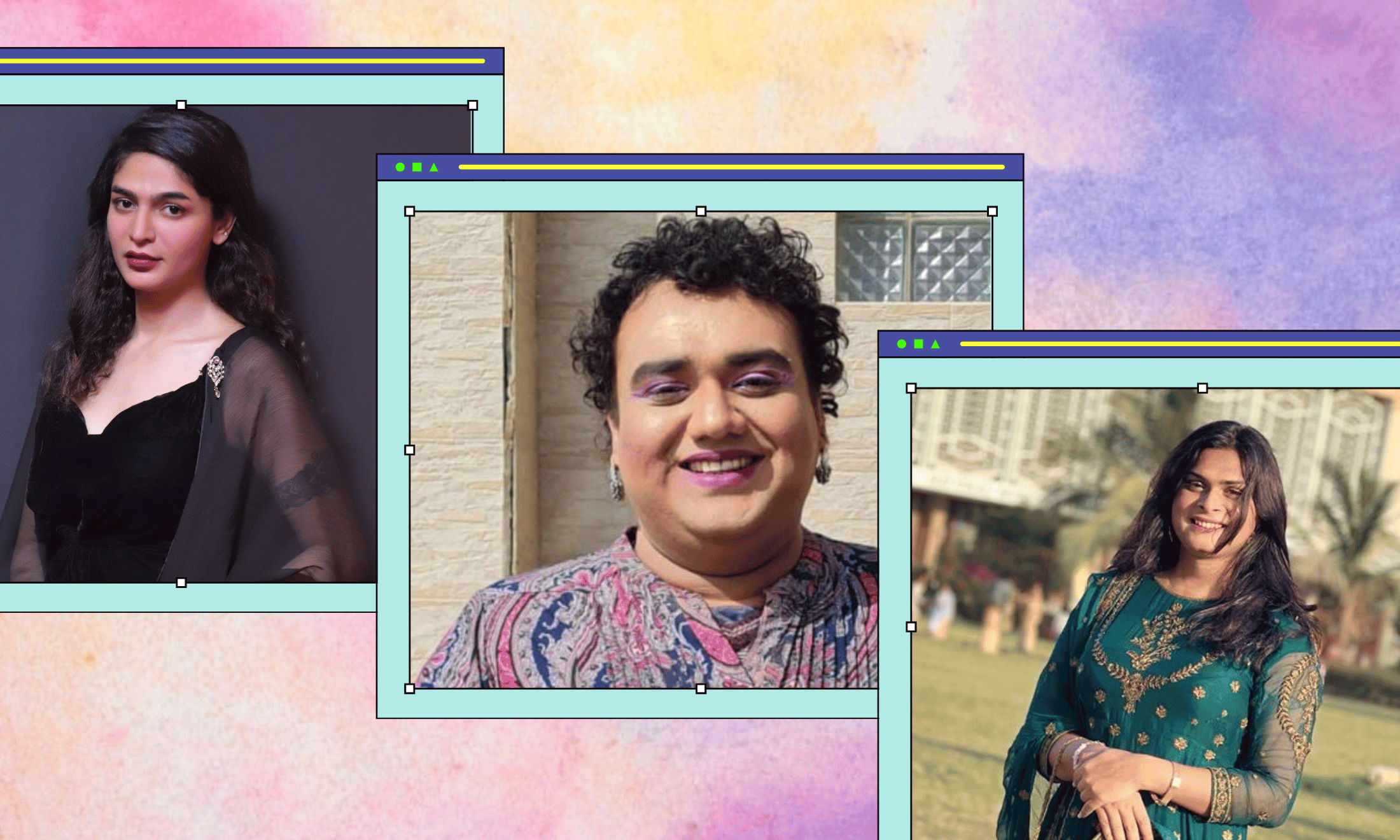

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?