Canva

‘You can’t really win’: the hyper-scrutiny of Black women’s bodies in music

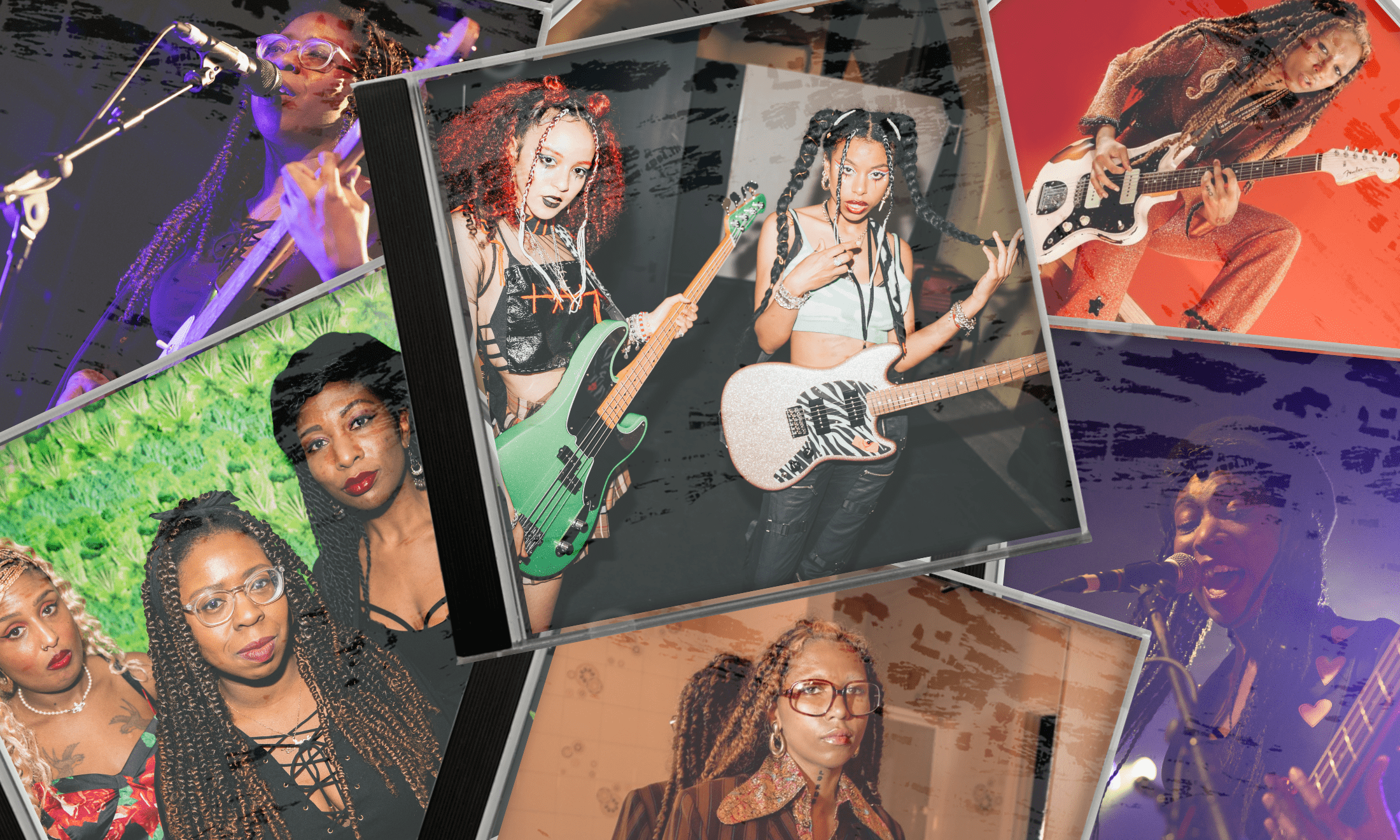

Laura Mvula, Raheaven, Aluna and LION BABE’S Jillian weigh in on existing as Black women in music, tackling stereotypes, shaming and invisibility.

Kayleigh Watson

05 Nov 2021

“Black women are only allowed to be one thing: sexualised or heartbroken or empowering,” says London R&B talent Raheaven. The 22 year-old musician sounds downcast. “Why can’t we be perceived as multidimensional? Why can’t we be hot and hard working and intelligent and funny and talented at the same time?!”

It has long been established that Blackness is cool unless you are actually Black. Without getting into the history of Blackfishing, Black people – especially Black women – face challenges in navigating toxic and longstanding negative stereotypes about how they present themselves. For Black women in the music industry, these struggles are played out on an intensely scrutinised stage. The toxic mechanics of the industry fails the artists it capitalises from – a recent survey from Black Lives In Music found that 63% of 1,718 Black people working in music had experienced racism, with a disproportionate number of Black women noting how it had impacted their mental health, and that working in music had led them to feel pressure to change their appearance and style.

Sex sells, it’s a tried and tested fact – but when society only perceives Black women artists as either overtly sexy or invisible, there’s a huge problem. Megan Thee Stallion’s shooting and the subsequent memes showed that very often misogynoir only allows for Black women to exist as a sexy commodity that does not make room for empathy.

“White male executives perpetuate stereotypes because they don’t want to lose control over how genres influence culture”

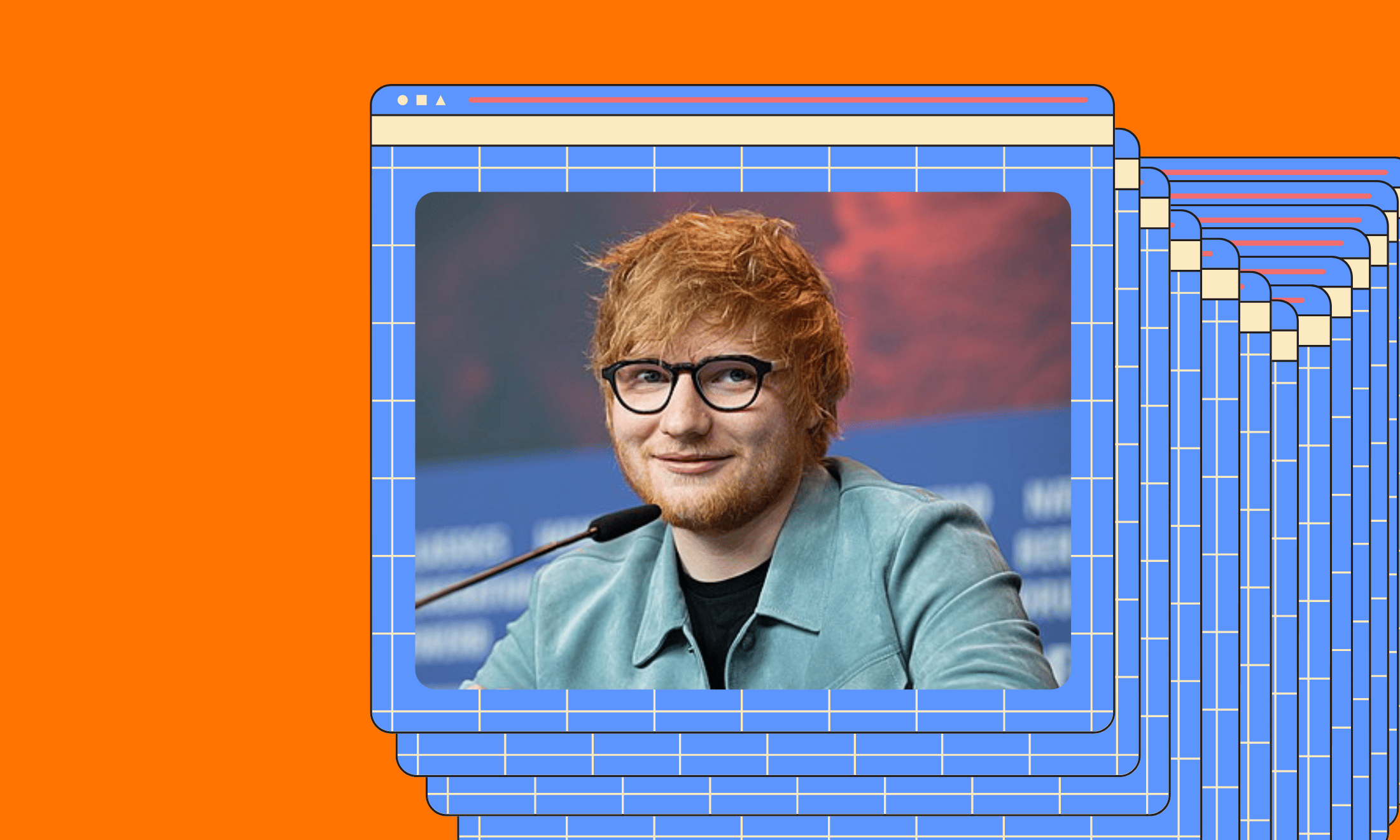

On the other hand, earlier this year former child star Chloe Bailey – one half of Beyoncé-hailed sister duo Chloe x Halle – found herself subject to hateful comments after sharing photos and challenges on her Instagram that saw her exploring her femininity. She later tearfully shared how the slut and body-shaming comments had been affecting her. Whether a Black woman complies to or defies a sexual image, it appears they cannot win.

It’s a sentiment that resonates with Aluna Francis, solo dance artist and one half of AlunaGeorge. “I will put my frickin’ money on [Raheaven’s] statement! It is specific to Black women,” she says, “White women [in music] are allowed to be vulnerable, they’re allowed to be sensitive, they’re allowed to be weird, they’re allowed to be aggressive – but without being sexual at the same time”.

For Black women, Aluna says, the thing that’s most celebrated is a “defiant showcasing of their bodies that forms directly into the stereotype of Black women being sexualised: it’s a duality, you can’t really win”.

Triple Mercury Prize nominee Laura Mvula also agrees. “Before having any public persona that was branded on me as a young musician, being a creative human could mean anything,” she notes. “There were no limits; there was no ‘okay, there’s room for you if you work, there’s room for you if you straighten your hair, [or do] a backflip’ – whatever it is.”

By pigeonholing Black women, it makes the process of marketing their music simpler for big record labels, no matter the artist’s background or the genre which they intend to exist within. “I think the main thing I got frustrated about was trying to communicate to white co-workers that being [and/or] looking Black is not just one thing,” explains Jillian Hervey of American R&B duo LION BABE.

“My hair was usually praised, not scrutinised, but they were afraid that changing up my look was somehow going to deter audiences. White male executives perpetuate stereotypes because they don’t want to lose control over how genres influence culture.”

Aluna echoes this: “If you’re entering R&B or hip-hop, which are the only genres that Black women are accepted in – apart from pop, which is just too competitive to even contemplate – then you’re gonna need to sell something.” It’s telling that the eclectic influences of AlunaGeorge and the dance sound of her 2020 solo album Renaissance did not fit into either ‘permissible’ genre of R&B or hip-hop. (In fact, as a young artist, Aluna had originally intended to make guitar-based indie.)

“The album cover is always something that I felt, where as much as the whole team were supportive, it ended up looking like me being a sexy girl on the cover of an R&B record”

Of course, we should not detract from artists’ agency. “One of the things I look at with Black women when they are hypersexualised, they are acting that out themselves, they have to physically do that – there’s a decision there,” Aluna continues.

“[And] there’s a duality in that decision: half of it is defiance against white beauty standards that makes Black women not feel sexy and attractive, and it’s also an act of rebellion against the stigmatism of the sex trade that has been a gateway for financial stability for lots of Black women. So that side of it is interesting. [But] it’s either get it all out or you’re irrelevant”.

This self-awareness of racial image becomes near impossible to avoid once in predominantly white spaces – and, of course, the music industry itself is a predominantly white space despite the mainstream success of Black artists. Those controlling the pursestrings, in positions of authority, are still typically white, cis men. Sometimes, in pursuing mainstream success, it seems impossible not to fall into the trap of presenting yourself in a specific way.

“Often, labels don’t necessarily have to make direct demands or requests in regards to the presentation of Black women talent because those entering the industry are intrinsically aware of the game”

“I think, instinctively because I saw every Black girl around me adhering to the straight hair requirement of navigating white society, I assumed that that was something I needed to do as well,” recalls Aluna of AlunaGeorge’s quick rise between 2012 and 2013, thanks to tracks like ‘You Know You Like It’ and the summer-smashing Disclosure collaboration ‘White Noise’.

“The album cover for [debut] Body Music is always something that I felt, where as much as the whole team were supportive, it ended up looking like me being a sexy girl on the cover of an R&B record, and I was like, how did that even happen?” In hindsight, although she was shot by a woman and her musical partner George was supportive of however she decided to present herself, Aluna concludes she channelled her own internalised expectations of how Black women should conduct themselves onto the final image. She calls the shoot a “pivotal moment of awareness” for navigating these internalised messages and pressures to “be sexy”.

This internalised shrinking is also echoed by Laura, who recalls an incident at the 2014 BAFTAs. It was one of her first major red carpet appearances, and she remembers Tinie Tempah’s manager Dumi Oburota telling her to “stand up straight, shoulders back, you know you’re a queen”. Laura felt confused, as she had been used to playing a certain role, one that was “tolerable, kind of smiley, not too bold, not too harsh, not too much… that’s what it means to be Black British and growing up in this country.”

Often, labels don’t necessarily have to make direct demands or requests in regards to the presentation of Black women talent because those entering the industry are intrinsically aware of the game. But is an artist’s success impacted by refusing to conform to the hypersexualised status quo? As one of the most commercially successful and body positive artists currently active, Lizzo has managed to subvert many of the body expectations of Black women artists.

But she too is not immune to insecurities; there have been times when the activist has shared her hurt on social media about the trolling and abuse she recieves online. “I would watch things on television and I would look at magazines and I would not see myself,” she remarked in a 2019 interview with British Vogue. “When you don’t see yourself, you start to think something’s wrong with you. Then you want to look like those things and when you realise it’s a physical impossibility, you start to think, ‘What the fuck is wrong with me?’ I think that took a greater toll on me, psychologically, growing up than what anyone could have said to me.”

“I do feel that Black women are fighting against [preconceptions] now more than ever”

In many ways, Lizzo is an exception to the rule, and may be a symbol of progression in a rigid industry thanks to fan culture and the diverse representation found on social media. Then again, Missy Elliott rose to fame in the late 1990s and it doesn’t seem like all that much has changed. Jillian, however, feels hopeful for the next generation of talent. “I do feel that Black women are fighting against [preconceptions] now more than ever. We are changing the narrative by breaking the ‘rules’ and taking it upon ourselves to create lanes that are not there for us”.

And as an artist of the next generation, Raheaven gives some hope for progress. While her appearance may have been subject to more scrutiny as an artist, she claims to be “unaware” of it, having been “fortunate to work with and be around people that wouldn’t scrutinise or compare [her to her] white peers”. She also reflects that “unrealistic” beauty standards exist as well as white beauty standards, but that she “wasn’t too conscious because your appearance is an opportunity to express yourself and not a place where you should feel the need to conform to rules and standards.”