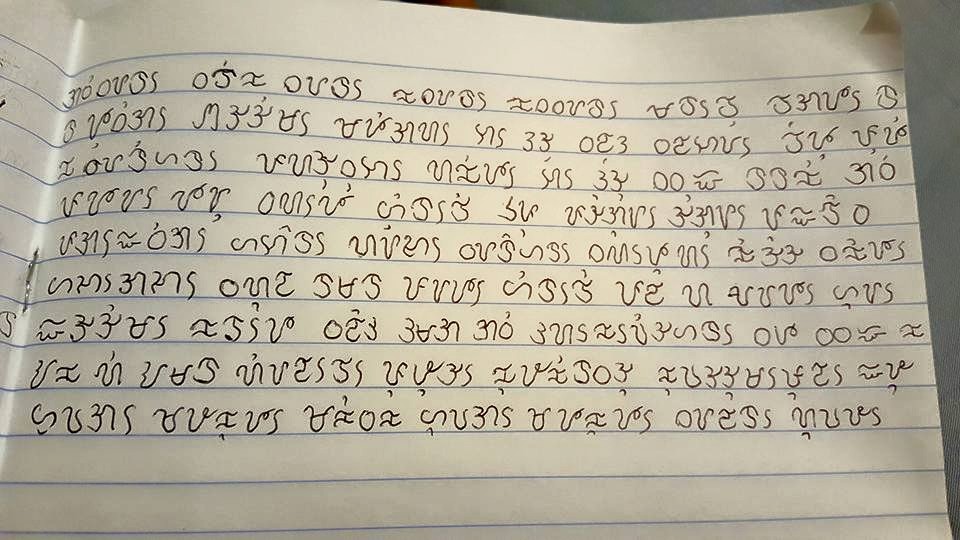

When I first participated in an online Austronesian community group, a member questioned me, in Tagalog, if I was Filipino. He thought by messaging me in Tagalog he could cleverly catch me out in an autonomous space he believed I shouldn’t be in. Little did he know that I happen to understand, read, write and speak Tagalog and even taught myself Baybayin and Suwat Bisaya, two ancient, Indigenous Filipino scripts.

I cordially fired back at his disingenuous comments, but the incident was hardly an uncommon one. Such interactions leave me drained and remind me that I am still read as foreign to fellow Filipinos.

I remember attending Filipino community schools back when I was a child in Riyadh, where teachers excluded me from studying Sibika at Filipino, or Filipino social studies and culture, in spite of me having the books, the interest and occasionally, voluntarily doing tests in Tagalog. Sometimes I even fared better than my classmates. But to my peers and teachers, they simply didn’t see me as Filipino and that was enough to warrant my exclusion.

Their ignorance and lack of exposure didn’t help their prejudiced understandings either. In the Philippines where 80 per cent of its people are Roman Catholic, many with Spanish names, I seemed almost antithetical by identifying as Muslim with an Arabic, Moorish name – امينة. With an American twang to my accent, it’s enough to have us all confused.

Prejudiced practices transcended the classroom to social settings. At recess, no one wanted to play around “Arabo” – a word derogatively used against me, yet indicative of a heritage I wasn’t even a part of. My dad was Sri Lankan. Categorically Moor, but not Arab. Perhaps to my classmates, the politically drawn earth between the Middle East and South Asia must’ve dissipated, since my peers saw no difference between them – as observed by their perceived interchangeability. Or perhaps, to them, my Muslim faith was synonymous to the Middle East.

But if it’s not “are you really Filipino”, then it’s “you look more Sri Lankan”. None of these utterances are new and none of them uncommon. It’s also interesting how non-Sri Lankans tend to say this to me, not Sri Lankans themselves, who also don’t recognise me as one of them unless I make that part of me known. I suppose no one really knows what to make of my strange face.

I can’t blame them entirely. We’re more or less conditioned by ideas of essentialist, nationalist ethnic identities, which are constructed in relation to others and each other, effectively operating by way of exclusion. But with 10 per cent of the Filipino population working overseas, some temporarily, some permanently, it seems inevitable that multiracial Filipinos will be born into the diaspora. Yet this diversity does not always translate into recognising their Filipino-ness.

This doesn’t seem to be a matter of multiraciality being perceived as inherently foreign or unwelcomed either. Incidentally, the Filipino mediascape is full of mixed Filipinos, including Anne Curtis, James Reid, as well as the current Miss Universe, Pia Wurtzbach. There seems to be several strands of perceptible Filipino-ness: the idealised monoracial Filipino and the idealised multiracial Filipino. Without satisfying either category, many native, mestiza and non-Spanish, non-white multiracial Filipinos remain isolated in the mediascape and in other aspects of active citizenry and governance.

So much so that when it comes to multiracial and mestizo Filipinos, it’s Filipinos with a white, western parent who tend to be more accepted – as the Filipino mediascape demonstrates – particularly if they have the desired “exotic” look. Foreign enough to incite curiosity yet familiar enough for acceptability. The rest of us are wondering in the abyss between the thin strands of recognisable Filipino-ness, waiting and actively seeking for that to change.

Because I didn’t see anyone like me in the media throughout my childhood, I pretty much hung on to anyone who was a mixed Filipino with a non-white, non-Filipino parent – and there were a handful of them as visible figures in the media, particularly in the diaspora. But the closest representation to me finally arrived in 2010. Up until then, I often searched “Filipino Sri Lankan” without much luck. I later broadened that to “Filipino South Asian” and “Filipino Indian” (not to suggest, however, that these identities are interchangeable), and trust my luck – that year, Miss Philippines Universe 2010 was Maria Venus Raj. While her story was vastly different to mine, there were parallels between us: born in the Middle East to a Filipino mother and a South Asian father. And in that moment in time, when I first came across Venus, she was fighting to be accepted, proving that she was a Filipino citizen with a valid birth certificate. Seeing someone like me in the media, for the first time in my life, felt like magic.

And I wasn’t the only one who must have felt that way. More multiracial Filipinos with a South Asian parent started showing up in beauty pageants, like Neesha Murjani and Parul Shah, some of them citing Venus Raj as their inspiration, although this representation remains almost exclusively to beauty pageants. We haven’t transcended beyond tokenistic ideas of non-white mixed beauty in mainstream media just yet, let alone other aspects of active citizenry, but I think we’re getting there.