In the run up to gal-dem’s birthday and release of our second print issue, we’ll be posting articles focusing on this year’s theme of ‘HOME’ . They will feature content centred around our experiences relating to what home means for us as women and non binary people of colour, in a personal and political sense. Tickets are still available here for the print launch on Friday 29 September.

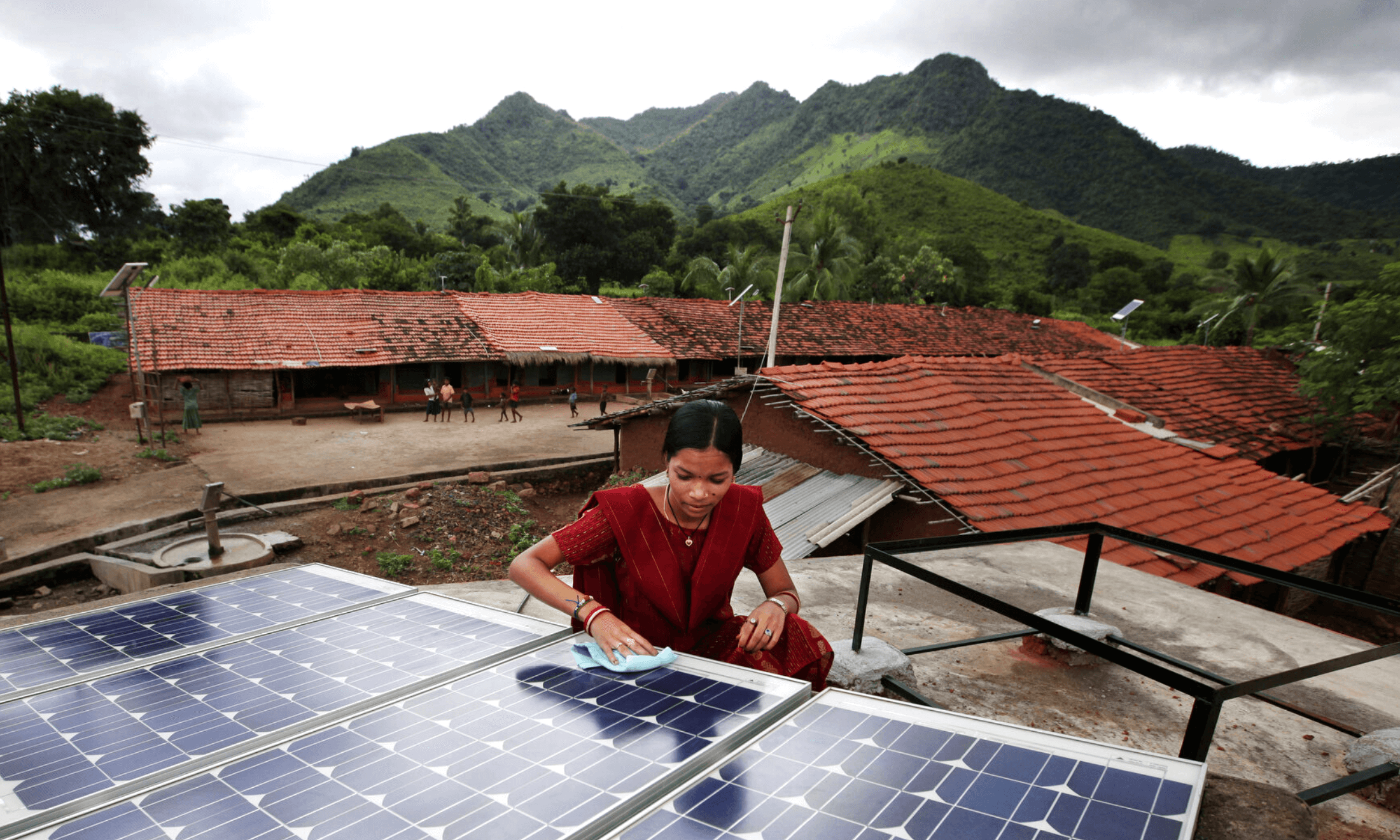

In post-independent India, a brilliant student began a promising career which, having already married and had two kids, took him abroad. Working for a large multi-national, my father migrated my family out of India when I was four.

Not everyone left India in search of the better life. However, it has never really been a question that better opportunities exist elsewhere. Life in India is not a walk in the park. Everything is a challenge in a country with a population of over one billion people. It is a society which has little space left for post-material needs and desires, unless of course you are a part of the elite, which my parents were not. They came from humble beginnings.

“They had none of the opportunities I was so easily given growing up as an expatriate child”

My mother and father met in a rural town in India in the state of West Bengal, back when phone calls and the internet didn’t exist. They had none of the opportunities I was so easily given growing up as an expatriate child. I went to the best schools and grew up with children from all over the world. I understood how different their world was through language, stories and trips to India every year. I speak the languages fluently, and am comfortable in their culture – adaptable qualities which make me feel proud, especially after the wave of Westernisation which has made many young people in India embarrassed to speak any language that is not English.

For me, there exists a term that is as comforting as it is confusing: “third culture kid”. The third culture child accompanies their parent into another society, and therefore assumes the role of visitor. In short, we don’t have a place in current bureaucracy. As children, we were too young to understand the world as unfair, so grew up happily holding onto the belief that whichever countries our parents would take us to were our homes as well. I held my Indian passport all through my secondary school education in Wales and my undergraduate studies in Scotland, trying to grow up as Indian as I could.

What happens when your developmental years and your ushering into adulthood takes place in countries that you do not have the legal right to live and work?

“I also became blissfully unaware that my actual legal status made me an alien there”

In my case, this resulted in severe cognitive dissonance, disconnection, deep-seated fear and anxiety, anger, desire to revolt, with doses of mental health problems. Somewhere over the years I began to not only feel European and British, comfortable with so many of the traditions associated with those regions, but I also became blissfully unaware that my actual legal status made me an alien there.

I did not grow up in India. I spent a year there post university and began to understand how difficult it would be for me to pretend to be a part of the society. I did not grow up there. I missed so many things about Europe. While I was living away, my parents were still in Britain, and I missed them. I was waiting to go back.

I am a Bengali migrant, irrespective of what age I left India. I gained much of my education in Britain, a country that recently plastered the face of Winston Churchill on their currency. A man that murdered my people in the Bengal Famine of 1943. Everyone seems to forget that when blood is shed it streams on for a long time, through generations.

“I am now being told that I am no longer welcome”

My family have been Londoners for almost five years now. I intend to pursue a Masters here. Yet, despite the expense of my education, my feelings of attachment and home, and my willingness to give back to this community as much as I have gained, I am now being told that I am no longer welcome.

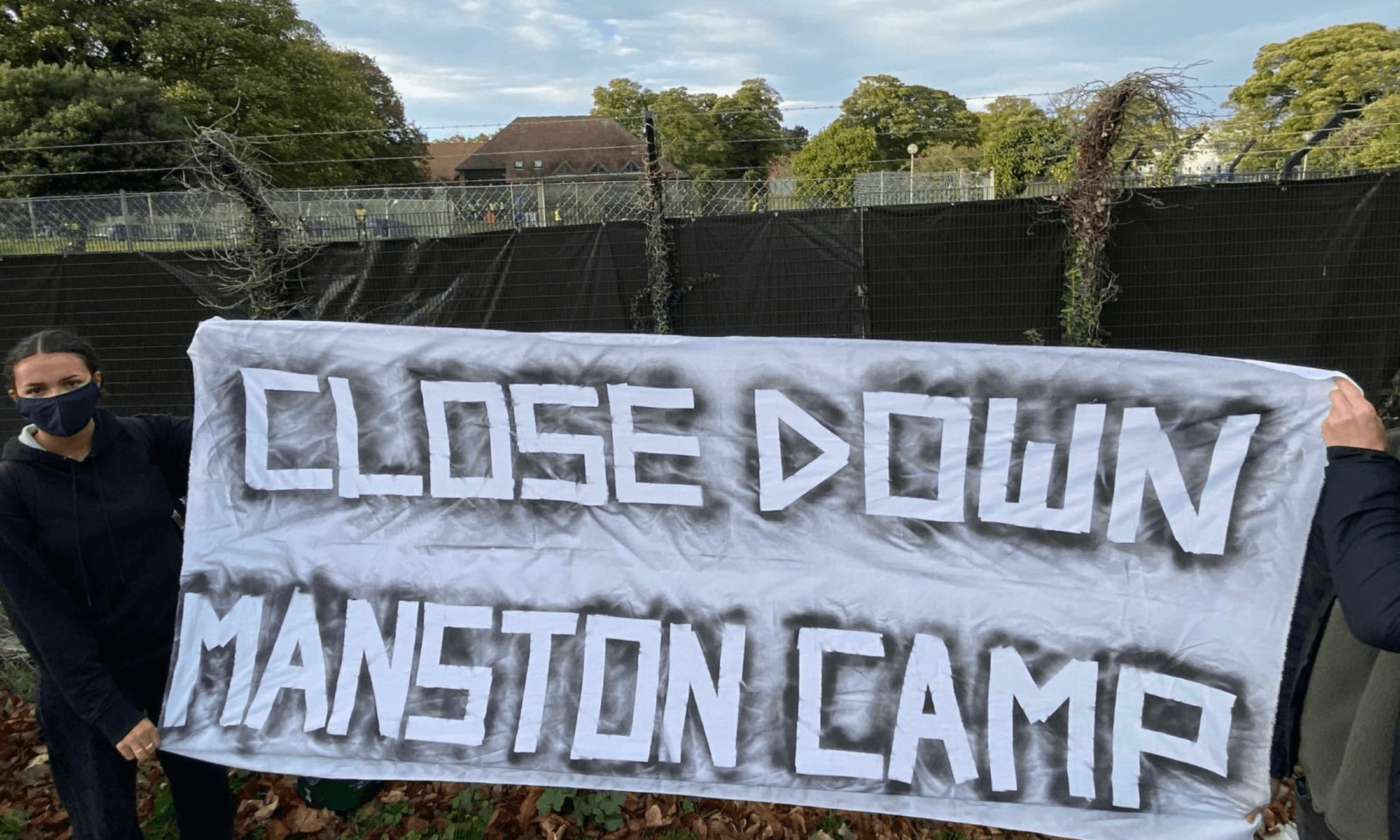

The first blow was the removal of the post-study work visa in Scotland. The second has been the recent administration’s behaviour, in particular that of Theresa May, who has shamelessly revealed her utter disdain for anyone non-British. Finally, the attitude of the far-right indicates to me that we should all just leave.

Should someone that has studied and grown up in a country be told to simply pack up and leave? Does it do justice to Britain’s history as an imperial power to remove a young Bengali female from the soil of a nation which at one point murdered her people? I have many questions, and my future depends on the answers.