Carmen Zografou

As an Arab artist, I’m tired of being told my music is hard to sell

Lebanese singer-songwriter Juliana Yazbeck argues it's time for Arab musicians to stop accepting themselves as niche, and to start taking control by building up their own industry.

Juliana Yazbeck

28 Feb 2020

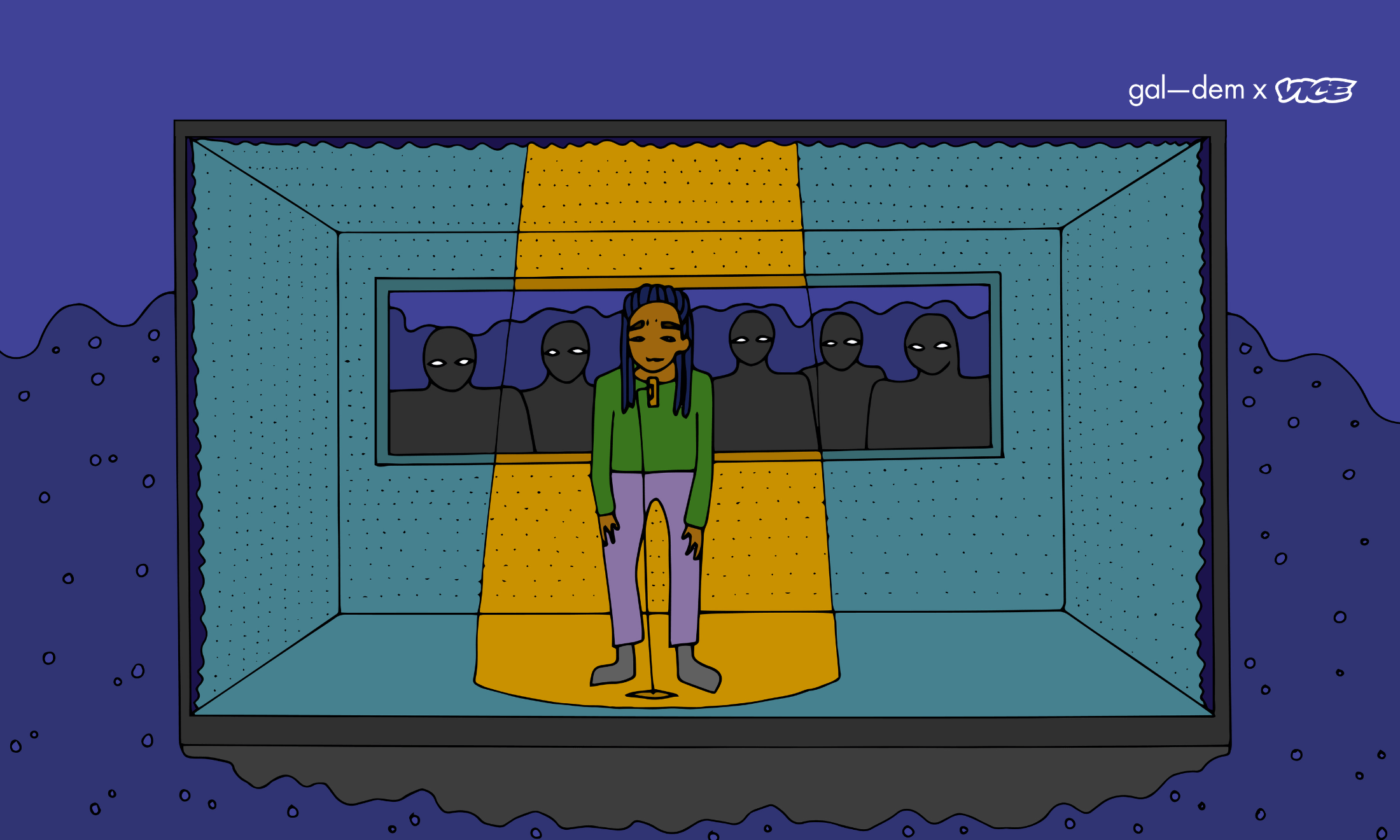

‘Arab people can be an industry in and of ourselves’: photography by Carmen Zografou

I am a musician, a woman, and a Lebanese first-generation immigrant. By these labels, I am the epitome of cool, the type of person everyone wants to support and empower. But my reality is very different.

Like many Lebanese of my generation, I was born outside of my country (in my case, the state of New Jersey) then grew up in the motherland. I immigrated to the UK almost 10 years ago. My music reflects this journey, which so many of us diasporans share. Combining Arabic singing traditions with rap and genre-bending electronica, I write as I think: bilingually and cross-culturally.

Yet apparently, my music is “hard to sell” and “hard to categorise”. A former manager of mine – also an Arab – said to my face that if I were “less niche” I could book bigger shows and get paid more (read: get paid what I deserve). Who decides how niche I am? I would imagine that decision is down to me. Meanwhile, acts like Coldplay appropriate and fetishise our people’s culture and suffering (see: their latest album Everyday Life), and we are meant to be grateful for being noticed by them. The same door that closes for us opens for white artists appropriating Arab culture.

“The same door that closes for us opens for white artists appropriating Arab culture”

– Juliana Yazbeck

But here’s something no one ever told us: We are the mainstream. Only through colonial practices have we been led to believe that rich white cis men are mainstream, while the rest of us must make do with being choked into the “diversity” categories, the “other” boxes, the “world music” scene. One of the first steps towards decolonising the arts is realising that.

We talk about the mainstream like it’s set and defined. And perhaps it is, in some circles. But other circles can and must exist. In spite of colonial narratives we have internalised, the shared lived experiences of billions of people around the world who are either immigrants or children of immigrants or multicultural or multilingual or any combination of the above are in no way niche. This is the global experience. This is the mainstream. So, when will our industry professionals stop bootlicking whiteness and have the courage to claim the mainstream as our own?

And that’s where the next step of reclaiming our autonomy in the arts comes in: by no longer seeing ourselves as marginal, we can start to reimagine how we work with money. In a conversation with a leading UK Arab arts promoter, I suggested we partner up with a brand or two to subsidise an event where the artists (myself included) were being underpaid, again. I argued that everybody wants to consume Arab culture (have you seen Billie Eilish’s latest Vogue cover?), so it’s about time we get paid for it. His response was, “Who do you think you are, habibti? No one is going to sponsor us.” Well, not with that mindset.

There appears to be an overriding sentiment among Arab arts organisations and fans that we belong in a certain place, that we must remain underground and underpaid. After a show one night, where I played alongside Sudanese-American artist Alsarah And The Nubatones and Lebanese-British DJ Saliah (all-femme Arab lineups always attract a crowd), a fan said to me, “Please don’t ever go into the mainstream. Please stay in the underground scene.” While fans understandably romanticise us as underdog heroes, they are largely unaware of the mental and financial strain we are under. Entering – or creating – mainstream spaces, conversations and contracts does not equal making commercial music. It simply means having the right to earn a living and feel safe.

“Until we understand our collective strength – and give ourselves permission to be mainstream – then we will remain starved, silenced, and struggling while rich white men grow richer at our expense”

– Juliana Yazbeck

We can be an industry in and of ourselves… if only we saw ourselves that way. Our numbers are immense, our buying power equally so. Until we understand our collective strength – and give ourselves permission to be mainstream – then we will remain starved, silenced, and struggling while rich white men grow richer at our expense. The power is in our hands. If our own promoters, organisations, and managers are the ones closing doors in our faces, then they can also choose to open them.

Ava DuVernay puts it beautifully: “I think a lot less about breaking down his door or shattering his ceiling and more about building my own house.” It’s a quote that I repeat to myself daily. And yet, as passionate as I am about that approach, when communicated to my community, it is met with confusion and fear. I recently had two meetings with two separate organisations that fund Arab arts, both managed by Arab women, where I excitedly talked about building our own teams, companies, and industry at large (we have the resources and the talent). I was met with the same looks of trepidation, and the same words – “but we don’t want to exclude anybody”. When will we realise that “anybody” is blatantly excluding us and telling us to know our place and stick to it?

In spite of all of this, the response to my music from the global community is overwhelming. I never knew that so many people around the world needed to hear what I was expressing. All I knew was I needed to hear it – and when I could not find it, I made it myself.

I am an Arab woman singer-songwriter who is telling her own story. I am not interested in being “chosen” by white people. I choose myself. And now, I call upon my community to choose us too.

Juliana Yazbeck plays Electric Ballroom, Camden, on Sunday 1 March, supporting Cairokee. You can buy tickets on the Electric Ballroom website.