Ignorance to the gross wrongdoings perpetrated by British colonial policies is constantly revealed when people ask me where I am from. Born in Britain, I am of Indo-Caribbean descent: my ancestors were amongst the hundreds of thousands of Asian indentured labourers that were recruited and effectively enslaved on plantations in British colonies in the 1800s.

Usually when someone thinks about the Caribbean identity, what springs to mind is the Afro-Caribbean community; rarely do people know that Caribbeans of Indian descent have been recorded as the largest ethnic group in Trinidad and Tobago and in Guyana today. And that’s because they have no idea how we got there.

This was proven again recently when a friend of a friend asked where I’m from. I told her that my dad and all four grandparents came to England from the Caribbean after being invited here to work. But I could see the confusion on her face as I explained: You, brown-skinned, with the surname Singh – you don’t look Caribbean.

“My ancestors were indentured labourers on plantations in Guyana and Trinidad” I explained.

“Oh! Wow. That is cool,” came the reply. But if she had any idea of the violence, racism and ruthless exploitation indentured labourers suffered, (which, unsurprisingly, she didn’t) would she have reduced my ancestral struggle to such an aesthetic? I hoped not.

“From 1834 onwards, British, French and Dutch colonisers established a system of indentureship where labourers could move to plantation colonies for a contracted period of around five years”

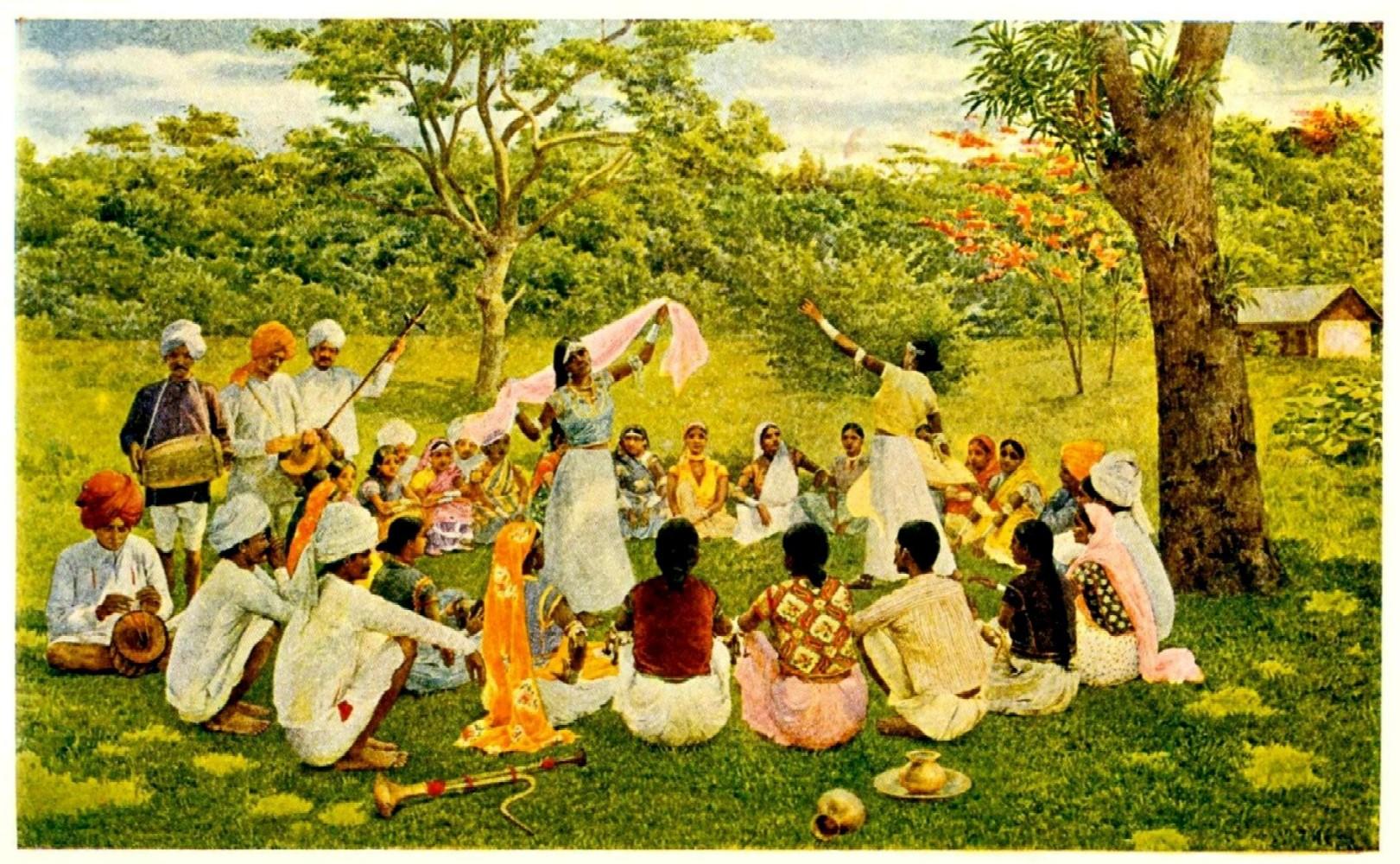

What our history textbooks leave out, is that the formal abolishment of slavery led to a void of labour on the sugar plantations in the Caribbean, and white planters looked mainly to Colonial India to fill. From 1834 onwards, British, French and Dutch colonisers established a system of indentured labour, where workers could move to plantation colonies for a contracted period of around five years, during which their employer would provide wages, housing and healthcare. Although they were “free labourers”, the system was plagued with fraud and deceit. Recruiters promised better living standards and many Indians (my ancestors included), were tempted by the lies and viewed the opportunity as an escape from unemployment, poverty and social unrest in India.

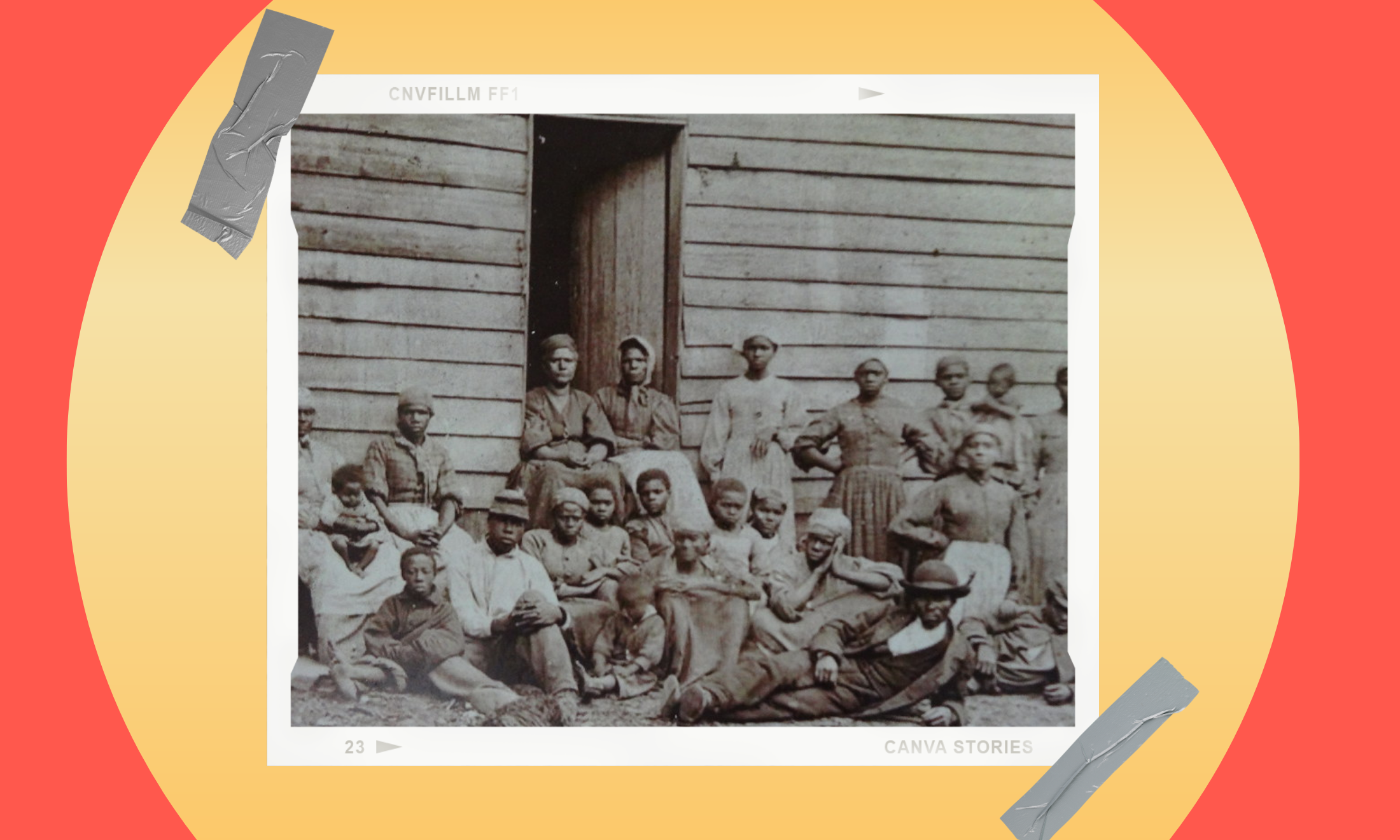

Labourers endured extremely heavy workloads, long working days and poor housing, usually living in overcrowded former slave barracks where food was scarce and medical attention was basic or lacking. Those under indenture were subjugated to the absolute authority of the British upper classes who used their power to starve, beat and cheat indentured labourers out of their wages. The Indian labourers were also put under immense pressure by the British to convert to Christianity. A divide and rule strategy turned Afro-Caribbeans and Indo-Caribbeans, Hindus and Muslims against each other to reduce the likelihood of uprisings. This strategy has had a long-lasting impact in the Caribbean with the same racial and ethnic tensions persisting today. Often the scars of colonialism aren’t even scars yet, but deep, open wounds that Britain refuses to take responsibility for.

From what I can see, the lack of awareness as to why the Caribbean has a large Asian “coolie” community, is borne from an inadequate school curriculum which barely scratches the surface when it comes to discussing atrocities carried out by the British Empire. And it’s not that I expect every British person to be able to recite a detailed history of colonial India. But indentured labourers suffered and sacrificed unspeakable amounts to bring prosperity and economic stability to Britain. Was their suffering not enough to earn a place in the history books? Seemingly not.

“Today’s British curriculum ignores much of the violence of Empire and avoids highlighting the impact it had on colonised peoples, as well as the negative and lasting legacy that’s still seen today”

Today’s British curriculum ignores much of the violence of Empire and avoids highlighting the impact it had on colonised peoples, as well as the negative and lasting legacy that’s still seen today. Perhaps this goes some way in explaining why a 2016 YouGov poll found that 44% were proud of Britain’s history of colonialism while only 21% regretted that it happened.

That our national curriculum erases difficult but important parts of British history is a grievance that has been raised time and again. But what’s also worth remembering, is that the curriculum is dictated by the government, and politicians on both the left and right have failed us.

Michael Gove, Education Secretary from 2010 to 2014, is renowned for altering the national curriculum to suit his personal worldview, and Gove happens to believe that: “too much history teaching is informed by post-colonial guilt”. He pushed for a more positive and celebratory rendering of the British Empire in schools to teach all British citizens “to take pride in this country’s historic achievements” – an idea that was supported by Prime Ministers Tony Blair and Gordon Brown in years previous.

Hence, frustratingly, pupils are still internalising the distortion that white Britain became a global power by itself – building the railways in India and civilising people of colour as they went. And by continuing to romanticise the Empire, the systemic presumption of white supremacy that fuelled colonialism largely remains unchallenged in the classroom.