Five Women, Vijf Vrowen, Lima Wanita: 300 years of the Indo diaspora

There are over two million people with Indo ancestry living in the world today, but how did such a diaspora form?

Marijke Stoll and Editors

02 Sep 2021

Welcome back to ‘Forgotten Diasporas’, gal-dem’s week-long series exploring histories of movement, survival and diasporic identity.

“I came from Indonesia, but inside I never moved”

Rich Brian, ‘Bali’

The history of the Indo people begins with the first arrival of Dutch merchant ships in 1595, when Dutch men made contact with Indonesian women and the first generation of mixed children were born. A people in-between, straddling two worlds and belonging in neither, the lives and fortunes of the Indos were closely tied to the colonial project. Brown Dutchmen, they called them. This is the story of the Indo people, told through the lives of five women in my family, each one a slice of the Indo experience.

Part 1: Adriana

When I think of Adriana, I picture a tiny body that somehow birthed 11 children, only four of whom survived into adulthood.

Adriana Louisa(e) Helvetius was born in 1735 in Batavia (Jakarta) and her tiny body encapsulated so much. She is my great-grandmother five times over, the Achterkleindochter (great-granddaughter) of Johannes Helvetius and of Altetus Tolling, both connected to the royal Dutch court. Descended from Johanna Magdalena, dochter (daughter) of Jacques and the unknown Indonesian woman. At only 15, she was married to Jeremias van Riemsdijk, 42 years of age. He was born in Holland and she was raised Indonesian, speaking neither Dutch nor familiar with her husband’s culture, his religion or the manner of his household.

She was raised in the East Indies style, like many of her Creole and Mestiza peers of status – cloistered and kept apart, surrounded by Sundanese servants and slavinnen (slaves), wearing adapted variations of the local dress. Only brought out to be married at tender ages, always to much older men. These young girls were culturally more Asian than European, whatever their racial background. They were nurtured almost exclusively by Indonesian women, spoke only the local native languages and Portuguese, which was still the preferred lingua franca of the island because they had been there first. Never Dutch, despite the best efforts of colonial authorities. Those silly Dutchmen, they despaired, thought it more stylish and elite to speak in any other tongue but their own.

Tiny Adriana represented a huge social advancement for her husband. That was the way of life under the policies of the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC), the Dutch East Indies Company: bring in immigrant men, bind them to the colony both through Asian concubinage, known as nyai in the Sundanese dialect (njai in Balinese), and the promise of attaining elevated status via marriage with well-positioned Eurasian women. To maintain control and prevent family dynasties, the VOC enforced a policy that only brothers-in-law and sons-in-law may be promoted. Never the sons, who were instead sent back to the Netherlands while the daughters remained behind in Java.

The unintended consequences of such policies were that money and power followed VOC Eurasian women of high-status. So, if a man newly arrived to the Indies wanted to advance in the company, this was who he sought out. A Creole or Mestiza wife, often very young, separated from her husband not just by gender, as they would have been back home, but also by culture, language, religion, geography and whole oceans of water, of understanding.

Adriana was the fourth wife of Jeremias; his first three wives having died in childbirth shortly after marrying. Adriana survived though, survived the birth and death of her first child at 15. She would live for 22 more years, alternating between pregnancy and birth. Jeremias would outlive her to marry once again.

In between, she lived as a Grand Lady of pomp and circumstance, like many of her peers. Accompanied by Asian symbols of status – parasols, betel boxes, and slavinnen whenever she promenaded the streets to church. The only time she was ever allowed outdoors, to be seen by other people.

Adriana, who lived in a luxurious prison.

Part 2: Dekkan

Dekkan, the opposite of Adriana. A slavin, slave.

She is recorded as Dekkan van Mandhar, meaning from Mandhar, of the Mandhar people from Sulawesi, one of the Greater Sunda Islands that make up the archipelago. It is a custom in Indonesia to have one name; so the Dutch gave places of origin as last names for their slavinnen.

My great-grandmother four times over, Dekkan was a slavin in the household of Willem Vincent Helvetius van Riemsdijk, the oldest surviving son of Adriana. A man regarded by his contemporaries as “stupid and uncultured”, but who had nonetheless become the largest landowner in the area, amassing much wealth due to the machinations of his father, despite the VOC’s efforts against nepotism. A man who was also infamous for his many mixed children, only some of them legitimate.

Dekkan gave birth to two of Willem’s sons and was freed sometime thereafter. I wonder if her experience had left an impression on her zoon (son) Lieve, not a legitimate son of Willem. For that reason, Lieve chose the last name Benjamins, married his nyai (concubine) Tjerewet and renamed her Arira Christiana, when his zoon, John Christiaan, reached the advanced age of seven.

Slavery was not a part of Dutch culture in Europe, but came to define the culture they created in the East Indies. Travelers to Batavia often commented on the laziness of the Mestizas – but not the Dutchmen, of course – who could not even bother to lift a glass of water to their lips because there were so many anonymous slavinnen to do it for them.

There was no benevolence; many died, their lives disregarded. Dire conditions, poor health, little clothing. Disposable. Dark bodies that could easily be obtained elsewhere and replaced with others. Background scenery, movable status symbols.

Of the men enslaved by the Dutch, it could be said that there were many limitations to their lives: what trades they could perform, the roles they played in this Dutch-Creole-Mestizo society, their age when they could be enslaved. Out of fear of rebellion, of course. The limit for enslaving Balinese youth was twelve because, it was said, they were particularly intractable.

Of the enslaved women, they were a sexual convenience for a male society that was starved of female companionship from the homeland. These women, forced to help with the running of the household, the execution of domestic tasks, including the sexual pleasure of their masters, the having and raising of their children. Many died in this way too.

Of the children born from these mixed unions, everything depended on the inclinations of the Dutch father. Some children were sent to the kampung (village) to be raised by their Indonesian relatives. Others were kept in the household but had only second or third or fourth status. The blessed ones were given a veneer of respectability via adoption after the fact, their mothers freed.

The story of Dekken and Lieve.

The truly elevated children were made legitimate in European eyes when their Dutch fathers married their Indonesian mothers, who were baptized and given Christian names, brought out into society as respected wives.

What Lieve did for Tjerewet, for John Christiaan and his siblings.

Part 3: R.A. Soedarmi

Of the Raden Adjeng Soedarmi, I know even less. She is a cypher; I have only fragments of memories. Finding traces of the R.A. Soedarmi, of her story, is a frustrating treasure hunt.

Raden Adjeng is the formal title given to an unmarried Javanese woman of nobility, either landed or of the royal family. After becoming a vassal state of the VOC in 1749, the Sultanate of Mataram was divided into two kingdoms, Surakarta and Yogyakarta, in 1755. Over time, the royal courts of Java would slowly cede power to the VOC and later the Kingdom of Netherlands, reduced to ornamental figureheads at the end.

Robin, a cousin, has a photo of a great uncle, remembers his title as Sultan. This tells me that Soedarmi may have come from the court of Yogyakarta. But this is simply a guess, amorphous as always.

How can someone be flesh and blood, yet a ghost at the same time?

Constance, mijn oma (my grandmother), tells me that R.A. Soedarmi was the eldest daughter. One day, she was kidnapped by the Belgian-born Bernard Pieter Jan Wierikx. They would have three daughters. The first two were adopted by Bernard, giving them his last name, a veneer of legitimacy. Oma Soedarmi was pregnant for the third time when Bernard died; she followed not long after, sometime in the late 1900s. So Tante (aunt) Annette’s last name was Vogel instead; in Dutch, bird.

The children, now orphaned, were living with a neighbor when a Catholic priest came by. He inquired about them, was informed they had no family, were just mouths to feed. I can only guess at the motive, but the priest adopted them. And so mijn overgrootmoeder (great-grandmother), Wilhelmina Dorthea Soesmira Wierikx was raised in a Catholic convent. Constance says, “My mother wanted to become a nun, but the sisters told her to go, have children, make a family.”

And so Wilhelmina did, marrying Janua Arend Benjamins in 1921. Janua, achterkleinzoon (great-grandson) of Dekkan, twice of Adriana.

Constance tells me that when she was a child, her mother brought them to see the current Sultan. When I try to find out more, from a child’s perspective she simply says, “Because she wanted to.” And I am left to simply wonder about that, and then ponder deeply about the strength that such a request must have required.

Constance says that one of the Sultan’s brothers greeted them warmly, bowed to them. The children were allowed to play with the kendhang (drum), the gangsa (metallophone), and other instruments of the gamelan (Balinese and Javenese orchestral music). “We were special, because they let us do that. They did not let the other children do that. We made such noise.” Constance laughs at the memory. She also says that they treated Wilhelmina with honor, with deference.

It would be Wilhelmina’s ties to the Javanese, through her mother, a Raden Adjeng from a royal court somewhere in Java, that would protect the Benjamins during the Japanese invasion in 1941. Robin explains, “My oma, your oma’s mother, maintained friendly relationships and respect with the Indonesians before the war. This saved us when the Japanese invoked the Indonesians to rise up against the Dutch colonial families.”

“Those relationships and respect,” he says, “were remembered by the people who were attacking the colonials.”

Part 4: Constance

Act 1.

Pictures of mijn oma Constance Benjamins, young and carefree in Indonesia, tell me that if it wasn’t for the Great War, she never would have left. Constance was only 16 going on 17 when the Japanese invaded, during their Dutch East Indies campaign, 1941-1942. When I ask her about it, the before-time glows golden like all idyllic memories of childhood do, before darkness and trauma take over your life.

Constance says they had to stop whatever they were doing, bow and scrape, whenever Japanese soldiers passed by. Sometimes, there was little to eat. One of her cousins was kidnapped by those soldiers, tortured and murdered at fifteen.

They only sent back his head.

Act 2.

After the Japanese left and the nationalist project began, after a period of ethnic cleansing where many died, all Indos had to leave Indonesia, to a place that didn’t want them either. But the Dutch were clever, they slipped in restrictions. To immigrate, you needed your paperwork, proof of citizenship. This was the trick. Who would have papers after a violent invasion, when so much was bombed and burned?

We had them though, sheer miracles.

Reluctant to go, Constance left with her husband Willie Wessels and their four children, 1952. Sailed on a passenger ship to the Netherlands. She remembers the Dutch being welcoming, even though she also says, “They said we were smelly, because of the spices in our cooking!”

Tante Barbara says, not everyone was received so warmly. “Apen (Apes)!” they would shout, “go back to the jungle!”

Only seven years and three more kinderen (children) later, Constance and her family would leave for the USA. Why? Amsterdam was too cold, she says, the wistfulness strong in her voice. Longing for the paradise of her youth, a rosy colonial past that can never be recovered.

Act 3.

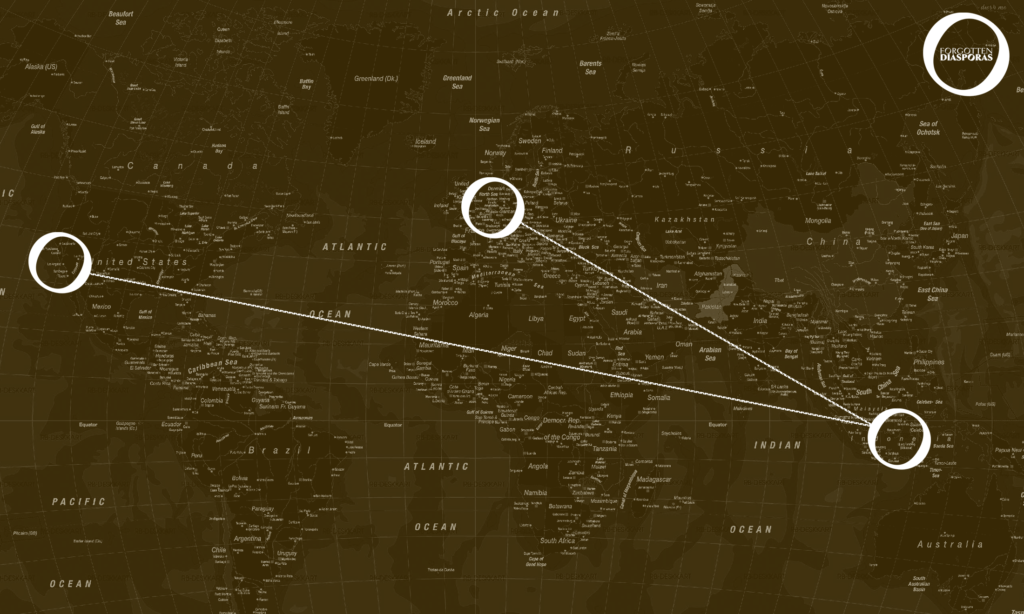

Last to leave Indonesia, but first to leave Amsterdam, Constance and Willie settled with their seven children in Southern California along with 60,000 other compatriots. Part of a trade deal between Indonesia, the Netherlands, and the USA. The first non-European refugees to be allowed in. Quickly forgotten about thereafter, their purpose in the grander political scheme fulfilled.

Constance had heard that California was warm. That there were plants like those in Indonesia. She says the Americans welcomed them.

But memories always glow more golden with time.

Part 5: Marja

When they landed, they found themselves in La Puente, California. Marja, mijn moeder (mother), grew up with some other Indo families but mostly surrounded by Mexicans. They all got along, though. The Indos, like the Mexicans, were brown; the food they ate was different from typical American food. They were both Catholic. Critical points of commonality in an often hostile country.

Food highlighted many differences. In everything else, Marja felt like a normal kid, except when it came to food. Whenever they went to eat at the tables of their white American neighbors, Marja and her siblings were awed by the modern food – T.V. dinners, canned goods, instant meals. By contrast, their food, Indo food, was so Dutch, so Indonesian. Pannenkoeken (pancakes) and oatmeal for breakfast, various combinations of rice, chicken and vegetables for dinner, cooked with the spices of the homeland.

Today she laughs at that, her childhood fascination with canned food.

Settling in California was best, she says, because it was already multicultural, in a sense. They stood out less as brown people. Perhaps this is why many Indos landed in places such as Hawai’i, New Zealand, Brasil.

Wherever they went, the Indos created ways to maintain their culture. A mixed culture born of colonialism, of elements that made for an uneasy syncretism. Only in the children did this mix work; Indonesian cuisine, on the other hand, could never fuse with Dutch.

In SoCal there was the club De Soos. Here they gathered to celebrate and be among other people who understood, who knew where Indonesia even was. Gamelan performances and dances; raw herring with onion and pickle on the rijsttaffel (rice table) alongside gado gado (steamed vegetables) and nasi goreng (fried rice). In these spaces, we shared our Indo-ness, our in-betweenness. Brown Dutchmen, Indo-Americans.

Indos that had remained in the Netherlands lived through a society that increasingly became open, though small flows of discrimination still flirt underneath. Indos in the USA, those first and second generations, pushed for assimilation, to become American. Because fitting in is survival. Always, forever.

The third, American yet apart, seeks to discover its Indo heritage, to understand our differences.

Food, as always, is a cultural touchstone around which we find common ground.

Women, as always, drive the story. In Indonesia, in the Netherlands, in the USA. My mother, Marja, taught me Indo culture through food. Sometimes I like to daydream that Adriana, Dekkan, and R.A. Soedarmi too, loved sambal badjak (chili sauce) as much as I do. That the threads weaving us together are more than simply blood, but also love, food, and survival.

The story of the Indo people.