A glimpse into the lives of transgender people in Kashmir

Despite ongoing discrimination and restricted life options, there are signs of hope for the transgender community, especially among the younger generation.

Shefali Rafiq

21 Dec 2021

Shefali Rafiq

This piece was originally published by Open Democracy.

Content warning: mentions of transphobia

On a cold winter’s evening, Reshma was the centre of attention in a room full of women in the city of Srinagar in Indian-administered Kashmir.

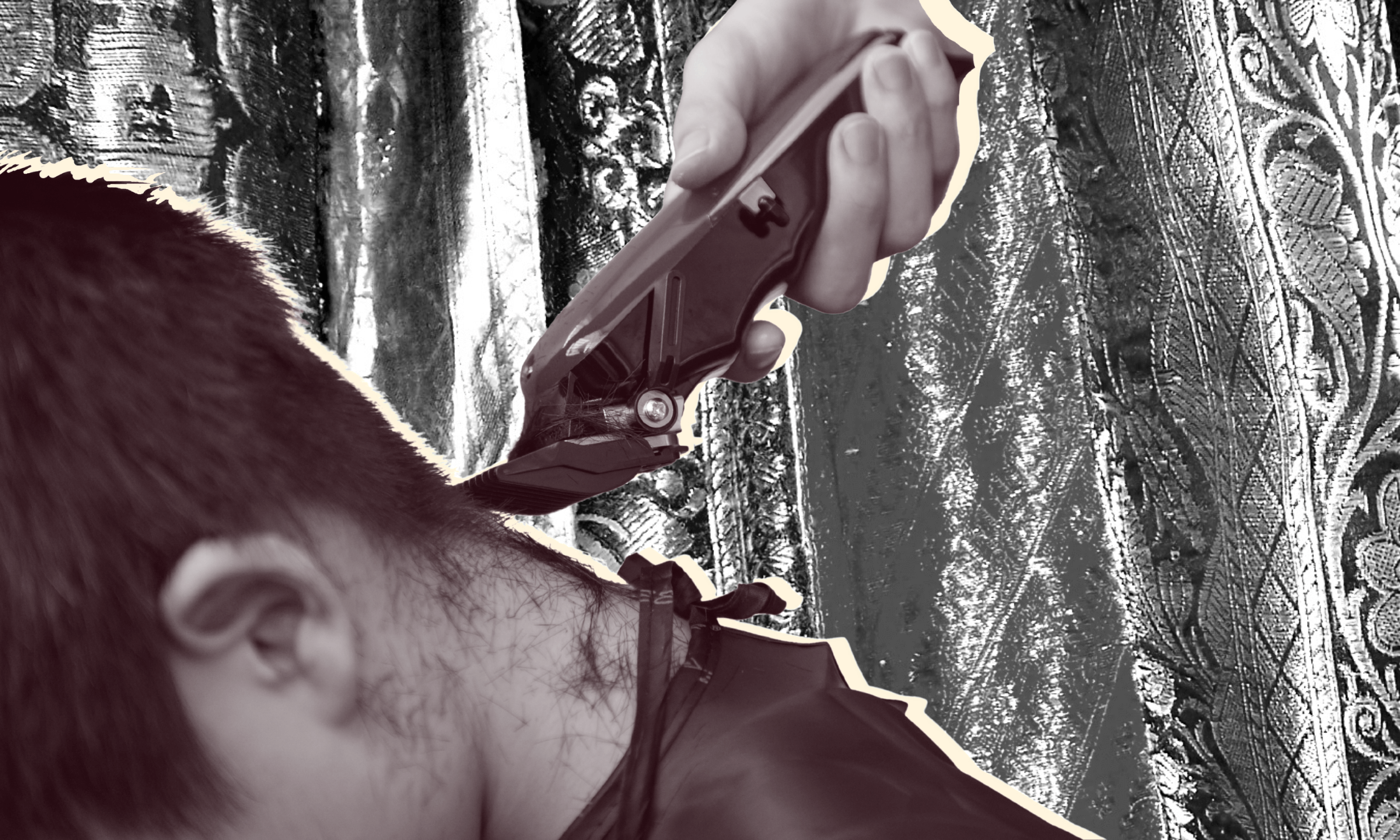

Reshma, who is a transgender, combed their short hair, took out an orange-coloured dupatta (long scarf) and a few anklets from their bag and put them on. They were about to sing at a wedding ceremony, something Reshma, now 55, has been doing since their youth.

Afterwards, Reshma folded the dupatta, removed their anklets, draped a shawl around their shoulders and left for home. Reshma is part of Kashmir’s transgender community, which numbers over 4,000.

The conflict-ridden Kashmir Valley is a bone of contention between nuclear neighbours India and Pakistan, both of which lay claim to it. The two countries have fought three wars over the Muslim-majority region since the partition of India in 1947.

Despite the region’s conservative outlook, transgender women have long been accepted as matchmakers and as performers at wedding ceremonies, which has provided them with a source of livelihood for decades.

Farah Qayoom, a sociologist and assistant professor at the University of Kashmir, said that transgender involvement in marriages is a decades-old phenomenon – in urban areas, at least. In more orthodox rural areas, this is “very rarely seen”.

Also, women are more accepting of matchmaking by transgender people, according to Qayoom. “Their interaction with women is not seen in a negative way; this could be a reason that they engage in matchmaking without much hassle,” she added.

Social media has also played a role in normalising their participation. Inviting Reshma and her companions to sing and dance at weddings has become a status symbol in Kashmir, she believes.

Reshma has attained celebrity status and videos of their singing have garnered thousands of views on social media. But their journey to fame has come at a cost. “In my early days of singing, I would get beaten by my family for singing, playing with girls and even growing my hair,” Reshma said.

“I always wanted to look like a girl. But I would have been killed if I had done that openly,” they said, while showing photographs from their younger days with long hair and make-up.

Change for the younger generation

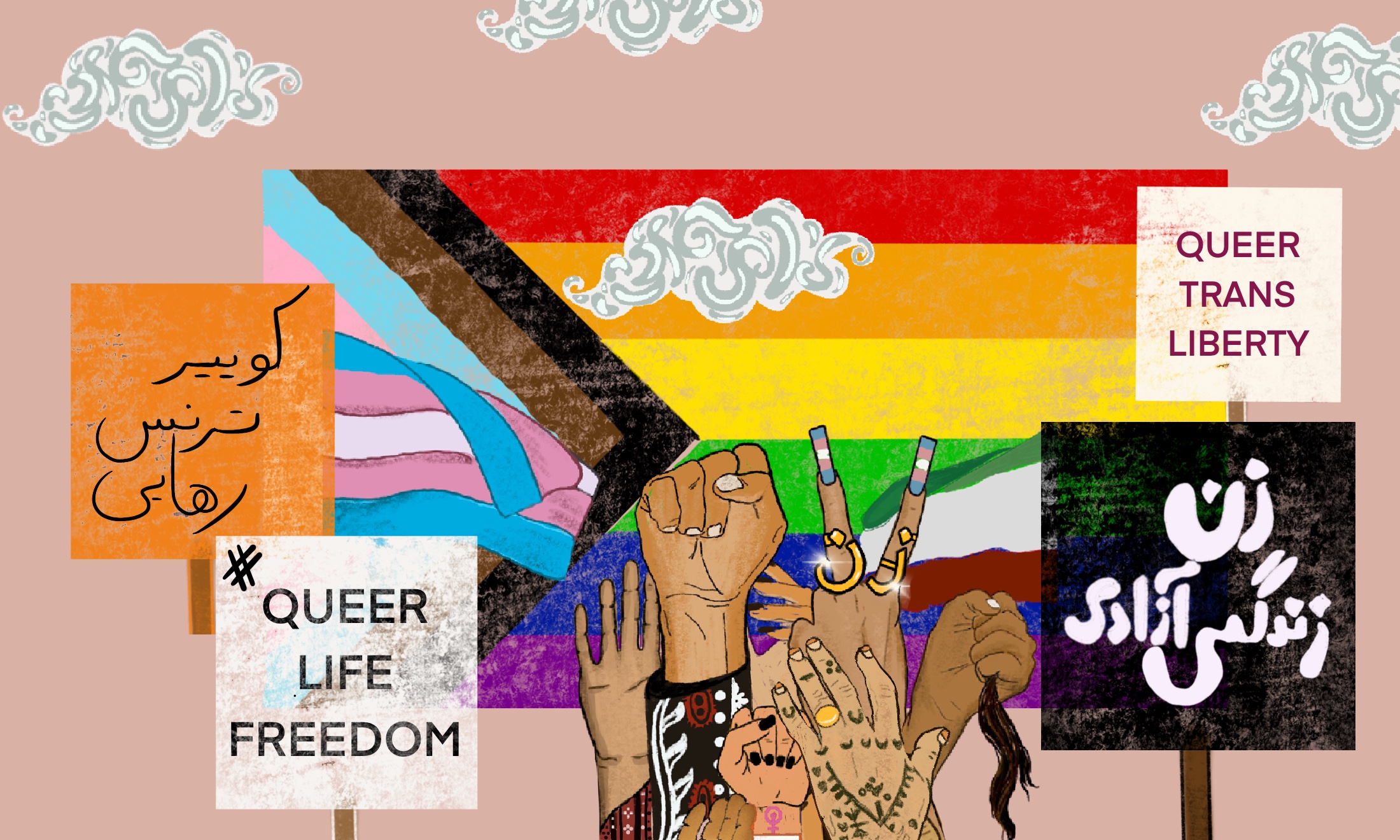

While older members of the transgender community only show their true identity at weddings, the younger generation seems to be breaking the shackles of patriarchy and the conventions of Kashmir’s conservative society. They say they are “proud” of themselves and don’t need to rely on a particular job.

Among this younger generation is Manzoor Ahmad, 21, who goes by the name of Manu Bebo and is among the few in the Valley who openly identifies as a transwoman. She works as a make-up artist.

She carries herself confidently and doesn’t mind the attention she receives while in public. This is something that is lacking among the older community members, who, she says, are “bound by religion and society”.

Manu was about 13 when she first realised that she was ‘different’. She was scolded by her parents for “being girly” and was often lectured by the elder members of her community who saw her ‘behaviour’ as a sin.

However, like other Srinagar transwomen, Manu has always been a bit rebellious. “I would tell them, it’s my life. The people who are talking about my clothes haven’t bought them for me. These are my clothes and I can wear whatever I want to,” she said, laughing.

Reshma’s experience was different. They said they were not bold enough when younger to wear the kind of clothes they wanted to: “Back then, it was not possible. We could not do that. We had responsibilities on our shoulders and we had to stay within our limits.”

Meanwhile, Manu has not only grown very popular on social media, but is determined to realise her dream of getting married, “While I am not in a relationship now, boys are crazy about me,” she said, as young men gathered around wanting to take selfies with her.

However, for Reshma, this is unimaginable. “I couldn’t have even thought of something like that,” they said, referring to getting married or settling down with a partner.

Discrimination and stigma

Reshma was recently forced to publicly apologise when a famous cleric issued a decree to “maintain distance from the community”, after a video of Reshma reciting verses from the Qur’an while playing a musical instrument (some people believe music is haram – forbidden) during a marriage ceremony went viral.

They received abuse on social media, “It took a strong toll on my mind, and I was confined to my house for many days,” Reshma said.

Manu’s journey to freedom has not been easy either. But, despite all the constraints and stigma towards her community, Manu manages to live freely as a transwoman. “I feel like I am a girl. That is it,” she proclaimed. “I don’t give a fuck about anything else. Before, I would get scared to upload my pictures, but not anymore.”

Aijaz Bund is head of the department of social work at a government college in the district of Pulwama. He founded the NGO Sonzal Welfare Trust with some community members, to build a supportive framework for the transgender community in Kashmir.

He describes himself as the first and the only activist working for the rights of the LGBTQI community in Kashmir, and blames patriarchal society for setting the limits – for everyone.

Bund realised the discrimination that transgender people face in 2008, when a transwoman came to arrange his sister’s marriage. “They weren’t even allowed to enter our home. I somehow convinced my mother to let them in. My mother washed each tea cup three times after they had left,” he said.

Bund said that almost every transgender person in Kashmir has faced violence at some point – whether physical or mental. Usually, “the first bully” they encounter is within their own family.

“It all starts with the family, who force the trans person to perform in a ‘normative’ way. If they don’t do it, the family starts abusing them physically and mentally,” he explained.

Being religious and transgender

Many transgender people in Kashmir believe that they shouldn’t change their bodies. A small percentage, however, take hormones or have sex-change operations.

According to 51-year-old matchmaker Babloo, who is trans and whose home is a meeting point for the local transgender community, Islam does not permit alterations to the body.

Unlike Manu, Babloo does not usually wear women’s clothing in public and, as with many of the older generation, dresses up only on special occasions such as weddings. “As soon as I reach home, I make sure to look like a man again.”

Although homosexuality is deemed a sin, both major schools of thought of Islam have declared gender reassignment surgery acceptable. Nevertheless, globally many transgender Muslims suffer rejection, socially and culturally, after reassignment surgery.

However, for Kashmir’s transgender community, there is a small ray of hope. Local cleric Ahmad Syed Shah Al-Qasmi told openDemocracy that in Islam there is no scope for discrimination on any basis. “Transgender people have equal rights. Their discrimination is unfortunate, and it is the fault of society that we have failed to stop the discrimination against them.”

As for young Manu, she believes that her body is hers to decide what to do with. “I would definitely change whatever I want in my body. It’s my body and I can do anything with it.”

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Against the binary: finding joy in myself and the freezing cold sea

50 years of Pride: Why I marched with Gay Liberation Front