Mr Hakan Küçükıslıkçı

Long before weighted blankets, there were Turkish yorgans

Exploring the weight of a dying craft.

Idil Galip and Editors

15 Jul 2021

One day, I was flicking through an American magazine when I came across an article about weighted blankets and their health benefits. “Weighted blankets are the trendiest way to achieve a good sleep”, the author wrote before claiming that they were first introduced and popularised by occupational therapists. The blankets are meant to provide a comforting sensation, which helps people who struggle with sleep disorders, anxiety or depression sleep better. And it’s not the first time I’ve heard of them either; my friends have been singing their praises for the past two years.

I do not own a weighted blanket, or at least the kind exalted for its virtues in Western media. However, I know exactly what sleeping under one feels like. I know, because I have slept under equally heavy, but much more colourful Turkish quilts called yorgans for all my life. Weighted blankets aren’t actually so new or revolutionary, considering they’ve been part of everyday and ceremonial cultures in the Near East for millenia.

Yorgan comes from an old Turkish word which means “cloak, shroud or swaddle” and has a long history as an established craft. Starting with the Seljuk dynasty, yorgancılık, or the craft of yorgan-making, had its heyday between the 16th and 17th century in the Ottoman Empire, Yorgan-makers were celebrated as master craftspeople who knew how to not only sew, embellish and design these quilts, but also excelled in treating the cotton and carding the wool that went into them.

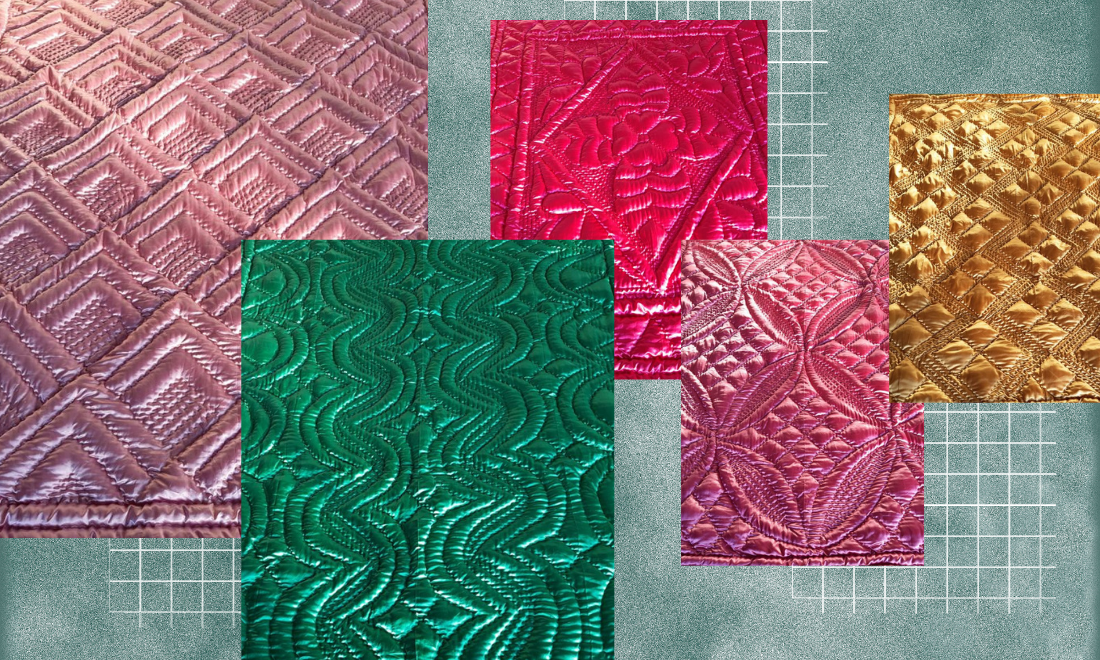

Yorgans come in a great variety of different local designs, but can be distinguished by their brilliant colours, such as hot pink, turquoise, lime green and bright orange, as well as their relative heaviness compared to factory-made, synthetic duvets. An average winter yorgan weighs around four to six kilograms and takes around a week to make.

“They witness births, deaths, marriages, family gatherings and parties. They’re given as gifts and are cherished as prized belongings”

These blankets hold an important place in the lives of the people of Turkey. They witness births, deaths, marriages, family gatherings and parties. They’re given as gifts and are cherished as prized belongings. They’re mended, overlooked and ultimately replaced, hidden in IKEA closets for being too gaudy, rural or Eastern. I think of them as therapeutic offerings presented to people during the most stressful periods of their lives, objects that are meant to provide comfort when someone is in a state of discombobulation, for instance, before a wedding or after childbirth or a circumcision.

Around 14 years ago, I travelled to my mother’s hometown of Eskişehir, a city in northwestern Anatolia, to attend my cousin’s circumcision party. Yorgans in their most humble and most decorated forms appear in my memories of this week. I remember laying on a floor mat and sleeping peacefully under the immense weight of a 40-year old yorgan at my late great-aunt’s rickety flat, feeling comforted by its heaviness every time the room shook with the passing of a train.

At the party, my cousin was smiling as he rode around on a white horse and opened gifts from family and friends, unaware of what was really about to go down. When we visited him after the deed was done, he lay visibly traumatised under a huge white yorgan embellished beautifully with gold thread. I don’t exactly know how comforting the yorgan was for him at that point, or if anything could be comforting after such an experience. I just know that the yorgan was an indispensable part of the larger, admittedly futile, attempt to make him feel better.

“The unbridled vibrancy of the yorgan defied the urban ennui that I so often felt when I lived in Ankara”

A few years later, my uncle got married to a beautiful woman who brought with her an antique dowry chest filled to the brim with embroidered fabrics and a special wedding yorgan. Every time we visited them in their new flat, I’d ask for permission to go into this chestnut vault to touch the textiles and gaze lovingly at the vibrant yorgan. The silky fabrics and the majestic chest that housed them felt out of place in their modern home. I thought they were too colourful and full of life to be here, in an eighth floor flat overlooking the brutalist landscape of Ankara – this infamously grey city which I couldn’t wait to leave behind. The unbridled vibrancy of the yorgan defied the urban ennui that I so often felt when I lived in Ankara. To me it symbolised a connection, albeit romantic and idealised, to an idyllic past.

When I was growing up in the 2000s, there were a few yorgan ateliers left in my grandmother’s neighbourhood of Bahçelievler in Ankara. I remember being mesmerised by the distinctive colours of the yorgans hanging up on the walls of the shop as I walked past them. As years went by and the ateliers started disappearing one by one, my initial childlike wonder would turn into melancholy every time I spotted one of these rare shops in the city. My tastes also changed as time went on, and no longer was I interested in these vibrant yorgans. Instead, I wanted to have subtle pastel tones in my room. I was embarrassed by the colourfulness of my Eastern culture and longed to be more European, more minimal and more understated.

The Westernisation of consumer tastes in Turkey and the flooding of cheap, factory-made materials and products as a result of the global textile trade are some of the reasons why yorgan-making is becoming obsolete. Sadly, while the cult of the weighted blanket grows in the West, one of Turkey’s traditional crafts is swiftly disappearing. And it seems that young people aren’t interested in being trained as apprentices for a dying craft. They fear their jobs will become obsolete before they have a chance to establish their own businesses, which makes it very difficult for craftspeople to transfer their knowledge to anyone, save for anthropologists and researchers.

“Sadly, while the cult of the weighted blanket grows in the West, one of Turkey’s traditional crafts is swiftly disappearing”

Capitalistic consumption patterns are killing this ancient craft in Turkey, all while amplifying the weighted-blanket as a novel, scientific, miraculous product that solves many sleep problems in the West. Yes, the yorgan isn’t scientifically developed to provide an equal amount of pressure in each of its corners and it isn’t used by occupational therapists in clinics. However it serves a similar purpose in my culture, which is to provide a sense of comfort through its weight.

Beyond its practical use, the gifting of a yorgan also communicates empathy, support and togetherness in the face of emotional turmoil. It symbolises the mundanity of human existence as an everyday object, accompanying you as you lay down at the end of a day and wake up to another. Yet it also marks momentous events in people’s lives, escorting them from childhood to adolescence to adulthood as a gift given before weddings and other important rituals.

However, there seems to be some renewed interest in the craft, as more and more young Turkish designers make use of traditional methods and textiles in their collections. For instance, both Rabia Gül and Istanbul-based label Cult Form have worked closely with master artisans to learn and incorporate this endangered craft into their designs; Rabia creating a collection of quilted jackets using Turkish textiles and motifs, while Cult Form introduced its yorgan collection last year, consisting of quilted belts, bras, shoes, and purses.

This creative repurposing of yorgans offers a different yet hopeful trajectory for the conservation of the craft, and helps keep it alive within Turkish collective consciousness, as it is introduced into the Western one.