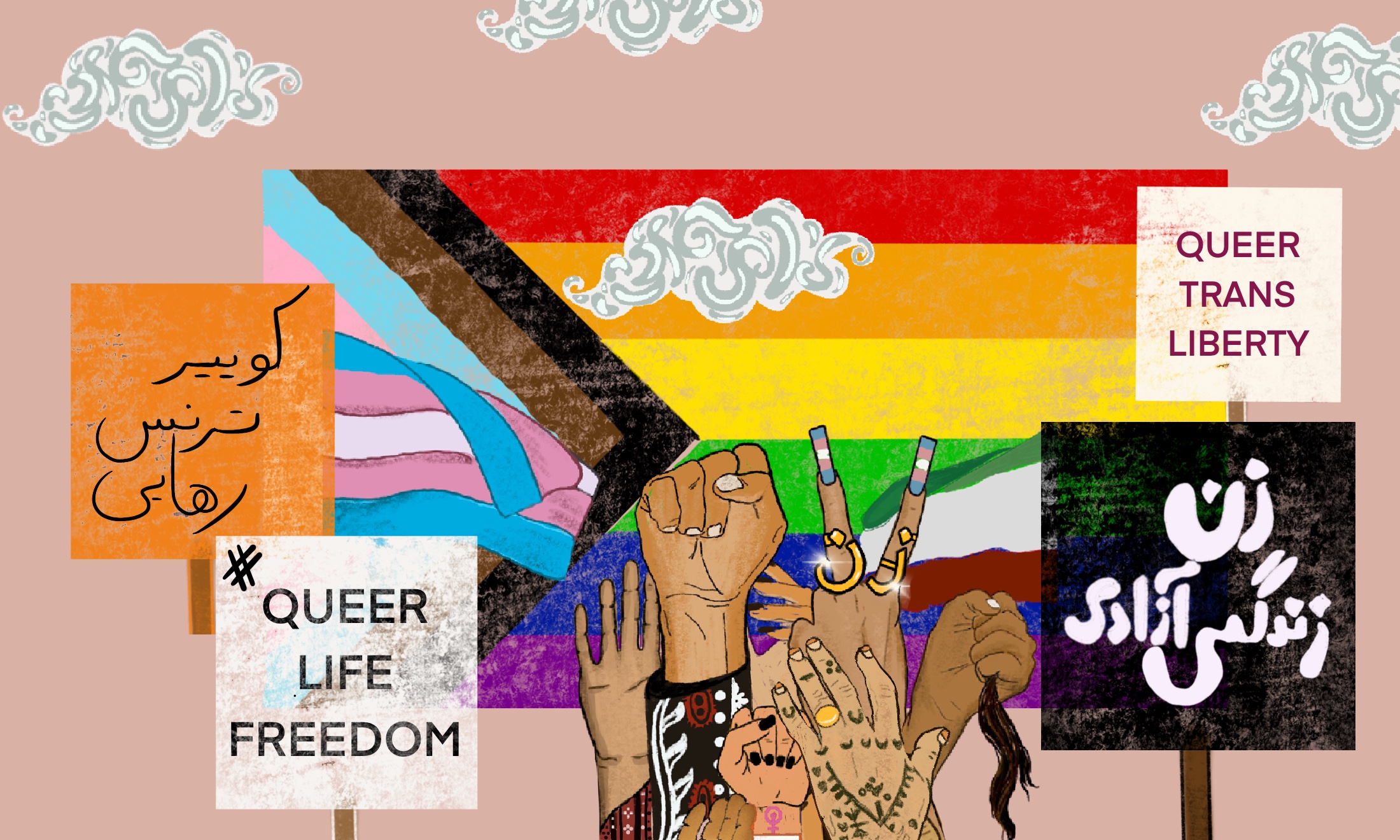

Collage by Karis Pierre via Instagram

Middle Eastern looks are ‘trending’, but where does that leave Middle Eastern women?

As memes of “Arab” Kylie Jenner circulate the internet, writer Parisa Hashempour explores how the "trending" aesthetic of Middle Eastern beauty is affecting women from the region.

Parisa Hashempour

27 Nov 2020

Growing up in North Wales, I wasn’t the only girl with train-track braces or a questionable side fringe. But in a rural, extremely white part of Britain, I was one of very few battling dark hair on my top lip, caterpillar eyebrows and unruly long, dark hair marking me as distinctly Middle Eastern-looking.

Fast-forward a decade – beauty trends have come full circle. The white girl who laughed at my unwaxed brows is part of the Huda Kattan fan club and the person who called me the p-word is slathered in store-bought melanin. Thanks to celebrities like the Kardashians and the new phenomenon of “blackfishing”, ethnically ambiguous features are “in”. But as the rise of fillers and faux features pushes us increasingly towards the same somewhat Middle Eastern looking Instagram-filter-face, can the collective acceptance of our looks really come from sudden Western approval?

The same approval created the “Arab” Kylie Jenner meme, where the celebrity’s new cosmetics campaign featured her comically resembling noughties Middle Eastern pop-stars like Haifa Wehbe and Ahlam. But all jokes aside, should we feel empowered by our trending features? And how easy is it to unpack life-long internalised racism once your features become fashionable?

On one hand, women from the Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) region can lean into their natural aesthetic and release childhood disappointments of never looking like the white heroines in their favourite rom-coms. The hourglass figure and brow laminations have replaced the slim-hipped supermodel of yesteryear. Today, Western teens are fake tanning and injecting their faces with filler in areas many Middle Eastern women already have natural plumpness.

“Today, Western teens are fake tanning and injecting their faces with filler in areas many Middle Eastern women already have natural plumpness”

Yet on the other hand, some of the most essential parts of our appearance are still deemed unattractive. Noses with a typical Middle Eastern bump or hook are seen as undesirable. And our women, with typically more body hair than white women, are often left behind from natural body hair movements in the West. Colourism still pervades our cultures and despite having naturally bigger lips and cheeks, women from the region still rush to inject juvederm or teoxane to intensify them even more.

26-year-old psychology student, Layla*, is second-generation Egyptian who grew up in Surrey. As a teenager she was infinitely bothered by her darker skin, Middle Eastern nose and bouncy, black curls. Each day was a battle with her mother, who tried to limit the heat damage inflicted on Layla’s hair through straightening. Thinking she’d be seen as “more beautiful” if she looked “more Western”, Layla fantasised about getting a nose job since she was a teen.

“I’ve always thought my nose is quite big, but it’s just a typical Egyptian nose,” she continues. Now, as thick brows are fashionable, Layla is becoming more comfortable with her looks. “Maybe it’s a mixture of increasing self-worth, but also the fact that beauty standards at the moment slightly work in my favour”, she reflects, remaining positive that the spotlighting of Middle Eastern beauty could lead to a long-term acceptance.

Fátima Lily is a 35-year-old half-Polish, half-Iraqi project manager for the NHS and an Instagram influencer. Caught between worlds, the light-skinned hijabi has a typically Middle Eastern nose and naturally hollow eyes. She avoided wearing heavy eye make-up in her early twenties, because “anything that looked typically Arab just wouldn’t do.” Fátima spent years bleaching and damaging her naturally dark hair, going to the salon with a photo of a white girl for a reference.

Today, she is proudly brunette and embraces her heritage, noting how prominent cheekbones, big eyes and big hips are now the fashion. “I’ve accepted my uniqueness, my culture, who I am and how diverse it is”, she says. ”It’s very empowering.” Fátima makes a point of following influencers who take pride in their noses to prevent her from getting back in the doctor’s chair. That said, she feels that women on her timeline are still influenced by European standards, which is why the teeny-tiny Nicole Kidman nose still reigns supreme in many surgery rooms.

“Despite some Middle Eastern features being embraced by Western society, it hasn’t stopped seeking out cosmetic procedures to alter the biggest identifiers of their heritage”

But despite some Middle Eastern features being embraced by Western society, it hasn’t stopped seeking out cosmetic procedures to alter the biggest identifiers of their heritage – their noses and the area under their eyes. Three years ago, Fátima had a periorbital procedure, which filled in the “hollow bones” underneath her eyes. Her doctor at the time, also of Middle Eastern descent, suggested the procedure unprompted.

It may be because in many Middle Eastern countries, popular culture continues to depict whiteness as the standard, and social media touts chlorine baths as an effective way to maintain a lighter complexion. Layla told me that in Egypt, photographers will airbrush you until your skin looks white, even if you don’t ask them to. But where has the plastic surgery craze come from?

Primitive plastic surgery may have taken place as far back as 3000 BC in Ancient Persia but new technologies meant modern procedures sprang to life in the region 70 years ago. In Iran, post-nose job plasters became signs of wealth paraded by teenagers. Over time, surgery became cheap, acceptable and accessible. In the 1980s, the former Supreme Leader of Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini, sanctioned rhinoplasty based on religious grounds, he said that “God is beautiful and loves beauty.”

Today, over in the UAE, Dubai is home to 47 cosmetic surgeons per million people, making it the city with the highest concentration in the world. Just a stone’s throw across the Gulf, Iran reported more than 500,000 cosmetic surgery tourists in 2019 and accounts for 4% of rhinoplasty procedures worldwide. By 2026, the cosmetic industry is set to reach a global net worth of $66.96 billion.

“In a world where whiteness is deemed supreme, it’s no wonder Middle Easterners in the West strive toward these unrealistic beauty standards instead of embracing their own”

I spoke to Dr Saleena Zimri, a cosmetics doctor operating in Yorkshire – an area with a large Middle Eastern community. “The sad truth is that they are all looking for a Western nose – it’s small, slightly upturned and short,” she tells me. “It’s the one thing on a Middle Eastern face that is not considered attractive.” In a world where whiteness is deemed supreme, it’s no wonder Middle Easterners in the West strive toward these unrealistic beauty standards instead of embracing their own.

But the most popular procedure in Dr Zimri’s practice? Tear trough fillers for hollowed out eyes like Fátima’s. “Genetically, Middle Eastern women tend to have deeper tear troughs and under-eye hollows. I tend to do a lot of filler work put under the eyes and the tear trough region.”

So how and why have these aesthetics changed? I spoke to Dr Sabiha Allouche, a lecturer in Middle Eastern studies at the University of Exeter. “Eurocentric beauty ideals, including a whiter skin tone, have been repeatedly shown to facilitate upward social mobility across very diverse social contexts”, she says, explaining that looking more “European” has become a marker of social status. “What’s more, the instability of the geopolitical region plays a role too. Given the region’s tarnished public image in western media and foreign policy – as a space of Islamist zealots and terrorists, looking ‘European’ becomes a mean to make the Middle Eastern ‘other’ more familiar and more ‘trustworthy'”, Dr Allouche continues. Therefore the familiarity of Eurocentric features indirectly paints the image of a group lesser removed from their white, European neighbours.

“How empowering can current trends be when they only include those that pass as ‘just white enough’?”

Also, many Middle Easterners try to embrace a white aesthetic in order to “differentiate” themselves from neighbouring countries. Iranians often refer to their “Aryan” heritage, and women in Lebanon (who are naturally lighter) are considered the pinnacle of Middle Eastern beauty. In a world where the word abd (slave) is still often used to refer to Black people and where blackface is common in cinema, Middle Eastern anti-Blackness is a real problem. Which begs the question – how empowering can current trends be when they only include those that pass as “just white enough”?

“I love my natural beauty the way it is, but I should also enhance it – I should also do things about it”, says Kuwaiti-Palestinian law student and Instagrammer, Rawan Bin Hussain. The 23-year-old regularly touches up her face with fillers, laser treatments and botox. After spending time studying in the US and UK, Rawan feels like an outsider to the typical Middle Eastern glamour radiated in her home country. “People [there] look amazing! When I go to the Middle East I hate going out because I always feel underdressed”, she says.

This regional lean-in to beauty was echoed by other women I spoke with, but where does it come from? 23-year-old Alaa is from Lebanon and first got lip fillers after encouragement from her big brother. She insists it’s not pressure from the West, but something with deeper cultural significance. “It comes from the idea we have that a woman should do her best to look pretty and take care of her beauty. It’s necessary for a woman to look beautiful.”

Dr Allouche thinks it may be linked to women’s lack of security and liberty in the region. “We know from historical antecedence that in times of precarity, gendered norms intensify. As long as women are seen as society’s ultimate object – of fantasy or an object that can be exchanged in terms of marriage or social mobility, this element will remain.”

“Women use their bodies to express the disconnect between society and state and acted as a stark contrast to the everyday violence taking place outside their windows”

Furthermore, in a region fraught with conflict, Dr Allouche explains that Middle Easterners’ creative approach to beautification is no coincidence. “It’s something to aspire to, something that is beautiful, not as violent.” She adds, “it’s a space of make-believe, imagining another state of being, beyond the police, poverty, massive unemployment of young people.” Through makeup, women utilise state-sanctioned materials to push back and flirt with the state.

In 2011, a series of anti-government protests led to uprising in Bahrain. While men flooded the streets to fight, women bought tickets, queued and sat down to watch Kim Kardashian at a visiting conference. In this way, women used their bodies to express the disconnect between society and state and acted as a stark contrast to the everyday violence taking place outside their windows.

A lot of women from the Middle East resonated with the Kardashians, their dark features finally accepted as beautiful in American culture, which was already prominent on their televisions and mobile screens. The influence of such celebrities has brought beauty ideals that deviate from the perceived “white standard” into vogue. The light-skinned, blonde beauty who was the height of glamour in decades gone-by was unobtainable for Middle Eastern women. Instead, white women today come to see Dr Zimri hoping to achieve the fuller-faced look of bigger lips, higher cheekbones and brow lifts that many Middle Eastern women have naturally.

This change leaves me and many other Middle Eastern women feeling conflicted. “I get so many comments from people saying I’ve got a lovely tan”, says Layla. “But my skin colour is not a tan, it’s just my skin colour.” While Fátima is exasperated at how these trends fall short, “it says to us, great you have those features but you still have to change.”

Both women feel more confident in themselves today than they did when they were young and admit the changing standard of beauty has gone a long way to influence that, but the ethnic ambiguity that permeates present beauty norms highlights a dark truth – maintaining elements of whiteness is essential to epitomising the ideal. As long as we are white-passing we are beautiful. “People think I’m from Spain or Italy, I’ve got this diluted appearance of heritage,” said Layla, attributing this to the greater ease with which she fits modern beauty standards. “I think being a Mediterranean beauty is still more celebrated than being Middle Eastern.”

So as Middle Eastern women toast to our big brows, full cheeks and wide hips, let’s not forget to question why we’re being celebrated. We should consider the implications of these beauty trends and how they still fail to make space for women with darker skin or more prominent features. We should remember that trends have changed and will change again. So what will happen when our features are no longer fashionable?

*Names have been changed