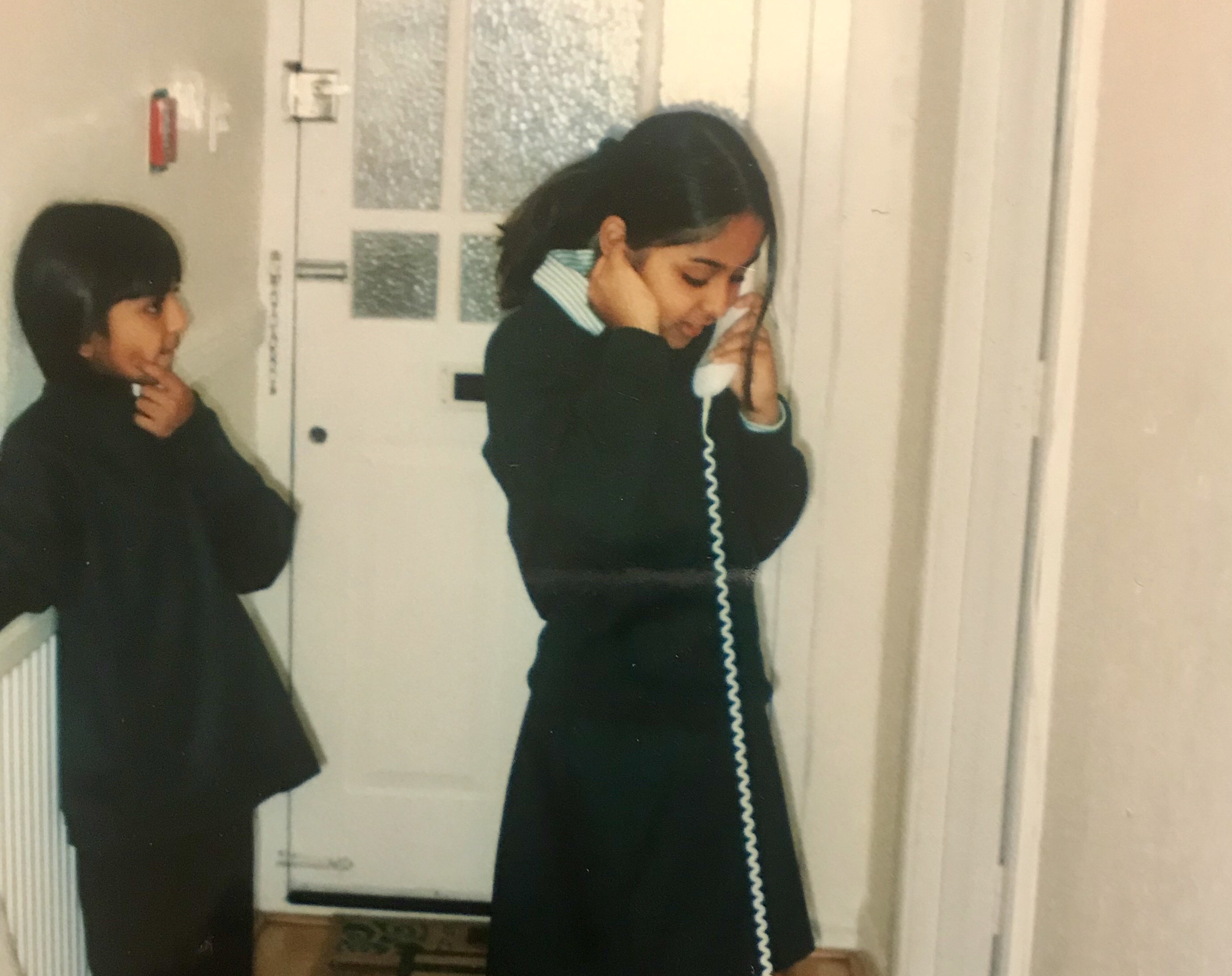

Image via Priya Minhas

Growing up, my family spoke of women who broke the rules like the titles of Friends episodes. There was the One Who Ran Away with a White Man, the One Who Got Married Twice, the One Who Never Married, the One Who Was Probably a Lesbian, and the One Who Smoked Cigarettes.

Sometimes these women ran away from their communities, and sometimes they were forced to leave. Either way, they lived in exile, resurfacing only when they were spotted in the supermarket, or on the tongues of others as a cautionary tragic tale. I know little else about these women. They were often of my mother’s generation, and their stories had been told, and retold, their choices discussed and debated, long before I was born. Some were victims, some were villains, others were both, but by the time their stories reached me, the entire lives of these women had been condensed into an adjective. We spoke of them then as our own common cultural references, my aunts referring to them as I do Britney’s 2007 head shaving or Kanye’s “I’ma Let You Finish.” We labelled and separated them, as we often do with women. The short one, the dark one, the pretty one. The Kelly, the Beyoncé, the Michelle. The Baby Spice, the Scary Spice, the Posh Spice.

I lived in fear of becoming one of those exiled women. I imagined them perpetually wandering the aisles of a supermarket, waiting to bump into someone they knew, waiting to be invited back home. Still, from a young age, I understood that I was connected to them. Our connection may not have been traced neatly on a family tree, but I understood that even in their exile, their shame could be transferred in the retelling of their stories from one woman to another like fresh ink across a page. The retelling of these stories was an act of prayer, not meant to shame but to instil a fear that would protect me and prevent me from ever becoming one of them. This is how I was raised—how not to be.

How Not to Be meant growing up with the promise of a life better than my parents had known. A life in which I would quietly, and often unknowingly, cash in on privileges paid for by the ones who came before me. My sisters and I were supposed to be the 2.0, the reason it was all worth it. Every school photo and each certificate placed on the mantelpiece was a step toward fulfilling this promise, each one an offering, a single penny placed at the altar to repay their sacrifice.

As girls, we were to follow a set of unspoken rules passed down through the stories of these women. A watchful eye was placed on our bodies from the moment we were born, and a large part of our cultural identity rested entirely on how we used them. Such was my dilemma, and the dilemma of many daughters of immigrants whose purpose seems to be the preservation of “our culture” as much as the progression of it.

Our cultural identity was the language, values, and customs my grandparents first carried as memories from India, but it was also the new words, recipes, and rituals that evolved as our family settled. It was adding masala to the spaghetti and eating samosas for breakfast on Christmas Day. It was the grocery stores, video shops, warehouses, and temples we built, and the communities that poured in and out of them. New roots were planted for us in these rituals. This was a way for my grandparents to create a more permanent state of belonging at a time when they could not pick up the phone or travel back home to be reminded of who they were.

The need to preserve and nurture all that was left of home was strengthened by the ever-present threat of having everything taken away. The fragility there, and here. Protecting these traditions was an act of self-preservation. We held on tightly to the things, places, people, and values that kept us safe, and could continue to keep us safe: a community and culture that reflected us at a time when our presence was often regarded as nothing more than a canvas upon which others could scribble out the terms and conditions of our stay.

My grandparents migrated to the UK with only the dream of opportunity. After years of watching the violence and destruction that came with British rule in India, they knew better than to carry over with them any hope for acceptance.

My sisters and I were sold a different dream, one of equality and assimilation. We worried less about our physical safety and more about the safety that came with “fitting in”. In our pursuit of this, and in our ignorance, we often strayed purposefully from these carefully preserved cultural cornerstones. But as we navigated our path to belonging, there were three rules we continued to accept with the understanding that as brown girls it was “our culture”: no sleepovers, no revealing clothes, and no boyfriends.

NO SLEEPOVERS

I grew up on the outskirts of London during the 1990s. As one of only a few Indian girls at school, I found my experience of girlhood consisted mostly of a slow surrendering to the idea that I did not have the right one. Instead, I had multiple versions of girlhood, none of which felt as though they belonged to me.

In some versions I grew up slowly, lagging five years behind the white girls, who filled water bottles with vodka and had their first kisses and broken hearts by the age of 15. In other versions I grew up fast, learning quickly which stories, words, and mannerisms to bring home and which to leave at school. Sometimes these versions threatened to collapse in on one another.

Having friends in my home carried the risk of exposing differences more easily hidden in the classroom. My mother switching to Punjabi on the phone or a framed photo of Ganesha meant explanations later. Constantly negotiating your difference as a person of colour means you are always explaining and excusing the plurality that holds you together, as much as it threatens to split you apart. My parents feared me growing up too fast, but juggling an identity that felt plural left me feeling old when I was young anyway.

Still, I often did have friends over, and on one occasion a friend remarked how lucky I was to have more than one type of cereal at home. I remember her words now because they remind me that I did not recognise the warmth and abundance of my own home. The truth is, I envied white homes for their “normality” as much as I feared them.

My parents’ reluctance to allow sleepovers grew out of a fear rooted in the values of the NO BLACKS, NO DOGS, NO IRISH Britain where they had been raised, the same values that had justified decades of systematic, physical, and verbal abuse toward people like us. Their reluctance acknowledged a deeper internalised fear toward white people and what they perceived as universal white culture. It was a fear rooted in memory. Of motorcycles being set alight, of being spat at, of being cheered out of a pub, of being watched, then followed, then beaten, of not being able to trust a schoolteacher, colleague, or neighbour to do anything but stand by and watch.

For the first ten years of my life, I lived in the same house in a town on the edge of London. My grandparents lived on the next street over, but we would drive to their house anyway, except when I threatened to run away, slamming the front door and walking over instead. My uncles and aunts lived in the same town too, and we shuttled from one house to another, often daily, stopping by to fix something, have a chat, drop the kids off, or deliver steel saucepans of leftover food.

When I was 11, my family relocated to the United States. We flew back home to visit often, and during one of these trips I returned to our old house. My dad asked repeatedly if I was sure I was ready to see it, the same way he’d asked if I was sure I wanted to see my grandmother at her funeral. I stood in our old dining room, stunned by how small it was even now that it was empty. How it strayed so wildly from what I remembered. For many Christmases three generations of my family had piled into this room, sitting at tables—borrowed from the local community centre—that snaked around the perimeter. The walls themselves must have expanded to hold us all.

I think often about the way I have recreated that feeling of safety. In the cities and towns I have lived in since, I place anchors by remembering which bartenders put the change directly in my hand rather than sliding it across the counter, finding an eyebrow lady who understands “Just a tidy”, and knowing which shortcuts to avoid at night. People of colour learn early to take responsibility for creating their own spaces and their own safety, whether that means choosing a university in a “diverse” area or simply looking for another person of colour in the room.

I live in New York now, and the truth is that I enjoy the anonymity it allows me. Community brings safety, but it also brings “What will people say?” Sometimes it is a luxury that I’m now able to define myself outside my community.

Other times I’m so homesick that I forget I’m living here by choice. For the women who ran away, and for those who were told to leave, I wonder how and where they created a home, and what happened when they didn’t have somewhere to return to.

In 1955, my grandfather arrived at Wolverhampton railway station, guided to the city only because he had seen the words written on a letter and nothing more. A taxi driver picked him up and, without asking for an address, transported him to the doorstep of an Indian family the driver knew. This house, and the man who opened the door and welcomed him in, became my grandfather’s first home in England. He spent the next few years sharing rooms with many other men like him, who pooled together their salaries. When my grandmother arrived five years later, she made a home out of these rooms, cooking for at least ten men at a time, men who had arrived on the doorstep like my grandfather once had.

Over the years, cousins, aunts, uncles, and grandparents passed in and out of my childhood home. Sometimes staying for months, other times stopping by for the evening. Our living room was the remedy. These were the days when you could arrive without calling first, when you could leave your shoes at the door and be welcomed in with a cup of tea or glass of wine, and dinner was always ready. I think back to my grandmother preparing food for each of the men in those small rooms, and my mother, now in America, thousands of miles away from those cousins, aunts, and uncles, but still always cooking extra.

As I entered my 20s and made homes of my own, friends would steal a t-shirt and makeup wipes before curling up in my bed, too drunk to go home, falling asleep to the sound of one of us thinking out loud in the safety of darkness. One night a friend showed up on my doorstep after leaving her boyfriend. One woman’s home becoming a sanctuary for another is a theme that has punctuated some of my deepest female friendships.

NO REVEALING CLOTHES

For a few years, I attended an all-girls school in the UK. We all wore the same bottle-green uniform, and every morning the top of the bus, the back of the classroom, and the bathrooms would be filled with girls huddled together applying makeup or rolling up their skirts at the waist until the hems skimmed their thighs. The girls who, like me, had multiple versions of themselves would roll them back down and wipe off their faces before returning home. These were girls who dared not fly out of the school gates to flirt with boys but instead flirted with the idea of another life. Girls who knew to stretch the lie just far enough so that it didn’t split entirely into two lives and force them to choose one.

Once my family relocated to the United States, I could wear shorts to school. My two pairs of denim cutoffs, one pink and one blue, are perhaps a seemingly insignificant detail, but wearing those shorts became just as much a part of our new American Dream as the yellow school buses, the Pledge of Allegiance each morning, and Chinese food that arrived in little white boxes on Friday nights. Before this, my sisters and I had worn shorts only on vacation. But now, in the suburbs of New Jersey, we were on a permanent one, because we were three thousand miles away from “What will people say?”

There is a photo of my grandmother taken shortly after she arrived in England. In it, her hair is cut short, falling just above her shoulders in relaxed curls. When I first looked at that photograph, at her standing next to a bike with her cropped hair, sleeveless top, and wide-leg trousers, I thought how she too had moved thousands of miles away from “What will people say?” But my grandmother cannot ride a bike. Her hair was cut during the year she spent in transit to England in order to make her look more westernised upon arrival.

Growing up, my relationship with my body, and what I did with it, centred on edging closer to whiteness. Whiteness—in pigment, not behaviour—is celebrated in my community, and “You don’t look Indian” was the “You’re not like other girls” for brown people. I chased it and accepted all of those scraps of “Pretty for a brown girl” and “You could be mixed” that always left me feeling empty. I suppose at one time those words meant safety before they meant self-worth.

Fitting in, it turns out, is a very physical process. I have spent years in a battle with my body, trying to make it compliant to the needs of others. I have tried to shrink it as though that could shrink my difference. Am I more welcome if I take up less space? If I can perch on the end, squeeze into the middle, hover by the door or against the wall and disappear? I have spent hours threading, waxing, and bleaching to achieve a feeling of cleanliness and normalcy. Hours running from store to store, trying to pack my body into something that says “Girl who deserves the job” or “Girl who can drink like the white girls”.

Growing up, I kept a diary for brief stints of time, discarding it whenever I felt my handwriting had deteriorated. I was too afraid to commit any real thoughts and feelings to paper, and instead I wrote lists—of all the things I thought I needed, to make being me a little easier. Things to wear and say to convince other people of my worth.

I wrote—very matter-of-factly—that I would like to stop growing hair on my arms and legs, around the edges of my lip and along my tummy. Which I wished were smaller too. I wished that I was allowed to shave, to wear crop tops and lip gloss and platform jelly sandals, and to pierce my ears. For women like me, who are rarely considered beautiful or powerful, there is always a list. And as a young girl, I had enough conviction to write it all down, believing everything that separated me from acceptance could be condensed neatly into a page of bullet points.

It was my aunt who eventually pierced my ears. She was a newly trained beauty graduate at the time. She sat me at the top of the staircase of my grandma’s house, marked my earlobes with a Biro, and told me to hold still. To everyone’s horror, what resulted were two new holes resting just above where they were supposed to be. Those little studs, sitting so close and yet so far from where I had hoped, summed up so many of my attempts at chasing ideals not meant for me.

After the earrings, it was the large pink plastic bag from the British clothes store Jane Norman, which girls at school often repurposed as school bags. Jane Norman sold what I called “Friday night” clothes. Everything they sold was body-con, halter-neck, strapless, slinky, and mini. Jane Norman was for girls who hung out at under-eighteens nights, girls who could flaunt their sexuality without shame or surveillance, girls who could dabble in their womanhood without being burdened with preserving their innocence. I had no business being there.

After that pink plastic bag, I wished for a body slim enough to wear tight jeans and a plain white tee and, after that, skin hairless enough to lie out in the park with the blond girls in June. Edging closer to whiteness was my own Sisyphean task, pushing myself further away from looking like the “others” only to be repeatedly reminded that I would always be “other”.

In America, I wore the shorts and the JanSport backpack and the American Eagle hoodie like the other kids. I went to homecoming dances and even had a white boy crush on me. But each day I spoke less and less, afraid that my accent would ruin the illusion and draw attention to the differences I had tried so hard to erase. Most days I didn’t speak at all.

In aspiring to whiteness, there was loss too, because it required forgetting. Forgetting the words in Punjabi because I was too afraid to speak it outside my grandmother’s house, letting my eyes glaze over at the mention of Diwali at school, lifting my shoulders in a shrug when someone asked whether dhal was spicy.

Sometimes I get a glimpse of who I could be if I stopped considering myself through the eyes of others. My potential spills out in front of me like a pint of milk that’s slipped from my hand—impossible to put back and for a second, as it pours uncontrollably, beautiful. It is in my most mundane moments in New York, showing my skin without fiddling with my buttons or holding hands in public, that I am sometimes reminded of how far I’ve spilled out.

NO BOYFRIENDS

I met my best friends in school. I suppose we were quite literally put together, but in hindsight, it felt like an act of fate that each of our last names began somewhere between M and P, placing us all next to one another across two rows. Together we accounted for nearly all of the non-white girls in the class, branding ourselves the “ethnixx”. We carved our girlhood out between those two rows, passing notes up and down to one another, talking about nothing and yet everything.

We shared an unspoken understanding that slowly shuffled my versions of girlhood into one. We were careful to say each other’s names correctly, chiming in defensively whenever a teacher tripped over their pronunciation. There was no need to make excuses for why someone could not sleep over or to hide the dark baby hair that stretched across our stomachs and forearms. We knew better than to reference certain topics or anecdotes in front of each other’s parents, and we knew to instinctively play alibi and cover for one another when a parent called asking after us.

For the first time I saw my adolescence through my own lens, and slowly my experiences were normalised. We each experimented with rebellion differently, but more often than not, our attempts were nothing more than small acts of subversion that we knew we could get away with. Some of us feared aunties, some feared fathers, and others feared God. Most of the time, we kept the secrets of others rather than our own. We lied to our parents to protect them. To lie was to play adult.

For most of us, falling in love was out of the question until we were at least eighteen, or married. Still, we exhausted our emotions, phone credit, and internet allowance with stories of our crushes and unrequited love. We took one another’s heartbreak and excitement seriously, as though these feelings had been reciprocated or existed outside our conversations and imaginations. We fell in love alone, together.

White people fall in love loudly. They have nine lives when it comes to falling in love. Nine love lives, that is. Over the years, I have watched white friends bring love interests in and out of their homes, onto their social media posts, and along on their family holidays. Even the most fleeting of romances are displayed with a confidence I can only recognize as recklessness. Rarely, in my own community, have I seen anyone introduce or even acknowledge a partner until it is confirmed they are the One. When I have been in love, I have protected and compartmentalised my relationship, sharing that person with only a select few and with bated breath. I have often protected others from my own heartbreak in an attempt to protect myself from “What will people say?” and from becoming the One Who Picked the Wrong Guy.

Brown love is public only in the sense that it demands accountability. Most of the images and stories I consumed growing up have led me to believe that brown women fall in love secretly and often with sadness or shame. They taught me that there is beauty, romance, and virtue in holding back, in cutting the action right before lips touch, and leaving any real display of physical desire, affection, and sexuality to exist within the imagination. So many of my own experiences with love, too, exist largely within my imagination. I have spent so much of my life entertaining those emotions only in the hypothetical that when I scan through my history of love interests, the reciprocated and the unrequited feel equally real.

I have never enjoyed going on dates because I have never managed to arrive for one without leaving half of myself at the door. Even the most promising ones require me to split myself in two—the other half of me watching the night play out, never quite believing it.

When I think about dating white men, I think of white women. Specifically, the white women who arrive at the same party or same bar and manage to compliment me and replace me on my own date in the same sentence. I have spent enough time watching white people fall in love to know the exact moment I become the sidekick. On every occasion, I have seen it coming. I’ve watched with admiration how easily and deliberately the white woman can lean her body into him, hold his gaze, and believe herself to be the object of desire without caution or shame.

In these moments, I wait for the anger to arrive. It’s not that I’m invisible to these women. They see me, but they simply don’t believe me to be there in that way. I don’t believe myself either, so I scoot over at the bar or go back inside the party. I call it a night. They act with an entitlement that I’m reminded I don’t have, laying claim in a way that I cannot. It’s a feeling of smallness that will not entertain the illusion, even briefly, that it could have been me, in a world that has repeatedly told me it cannot.

I fell in love for the first time somewhat unexpectedly and yet inevitably. Having grown up with the understanding that I was not allowed to date, doing so felt like something to be feared rather than celebrated. I feared the consequences of showing love, which also meant I feared allowing myself to be loved in return. Giving in to my emotions, as honest as they were, felt like betrayal. I had been defeated and became the girl living a second life. I was consumed with guilt, and as one lie shattered into ten and then 20, I felt myself becoming closer and closer to the women I had grown up being warned about. It’s easy to speak openly of the women we celebrate and model ourselves on becoming, yet perhaps it is the women we silently swear never to become that influence us the most.

My heart aches for brown girls who fall in love in the shadows. Whose love stories are confined to deleted messages, libraries, lunchtimes, and their imagination. Who can only laugh at the idea of meeting a boyfriend’s or girlfriend’s parents, making it Facebook official, or being walked home right up to the door. These are the girls who knew how to curate and filter themselves long before social media.

My heart aches because these are the girls who have learned to accept being loved only part-time, who must endure the pain of heartbreak by themselves, and then carry the shame alone too. The girls who can’t hear their parents say “You deserve better” instead of “What will people say?”

I once read that “a path connects one place to another, but it also measures the distance that separates two places. A line at once joins two points and keeps them apart.” Through the hopes, fears, mistakes, and ideals of my heritage, I learned How Not to Be. Those three rules—no sleepovers, no revealing clothes, no boyfriends—formed the line that kept me connected to my culture throughout my girlhood as much as it kept me apart.

Turning the experiences of the women who broke the rules into little more than cautionary tales led me to believe there was one acceptable and universal brown girl experience. Defining myself by how closely I followed those rules led me to believe there was a right way to grow up.

So, my girlhood meant growing up twice. My first coming of age was learning the rules. The second was breaking them.

This is an edited extract from “How Not To Be”, an essay that appears in The Good Immigrant USA.