Ning Yang

My mother used our culture as an excuse for emotional abuse

When does discipline cross the line and become child abuse?

Natasha Zhang and DiyoraShadijanova

21 Apr 2021

Content warning: mentions of emotional abuse

When people ask me about my mum, I usually say she’s an ‘interesting’ character. It’s much easier to use some random adjective that doesn’t have much meaning to describe her, than actually explaining the many cruel things she has said to me. I’ve been laughing off her behaviour for years, unable to fully comprehend why she treats me, her only daughter, like I’m nothing.

I moved away from home at the age of 15 to attend school in the UK and I’d only speak to my mum once every three months – she’d only get her updates from my dad. I thought it’d be much easier to have a relationship with her if there were fewer volatile outbursts, if our entire relationship was relegated to infrequent phone conversations. But a few years ago my father died, and now I feel forced to speak to her more often because she’s the only family I have left. But, recently her behaviour has gotten much worse. In fact, my therapist described it as emotional abuse.

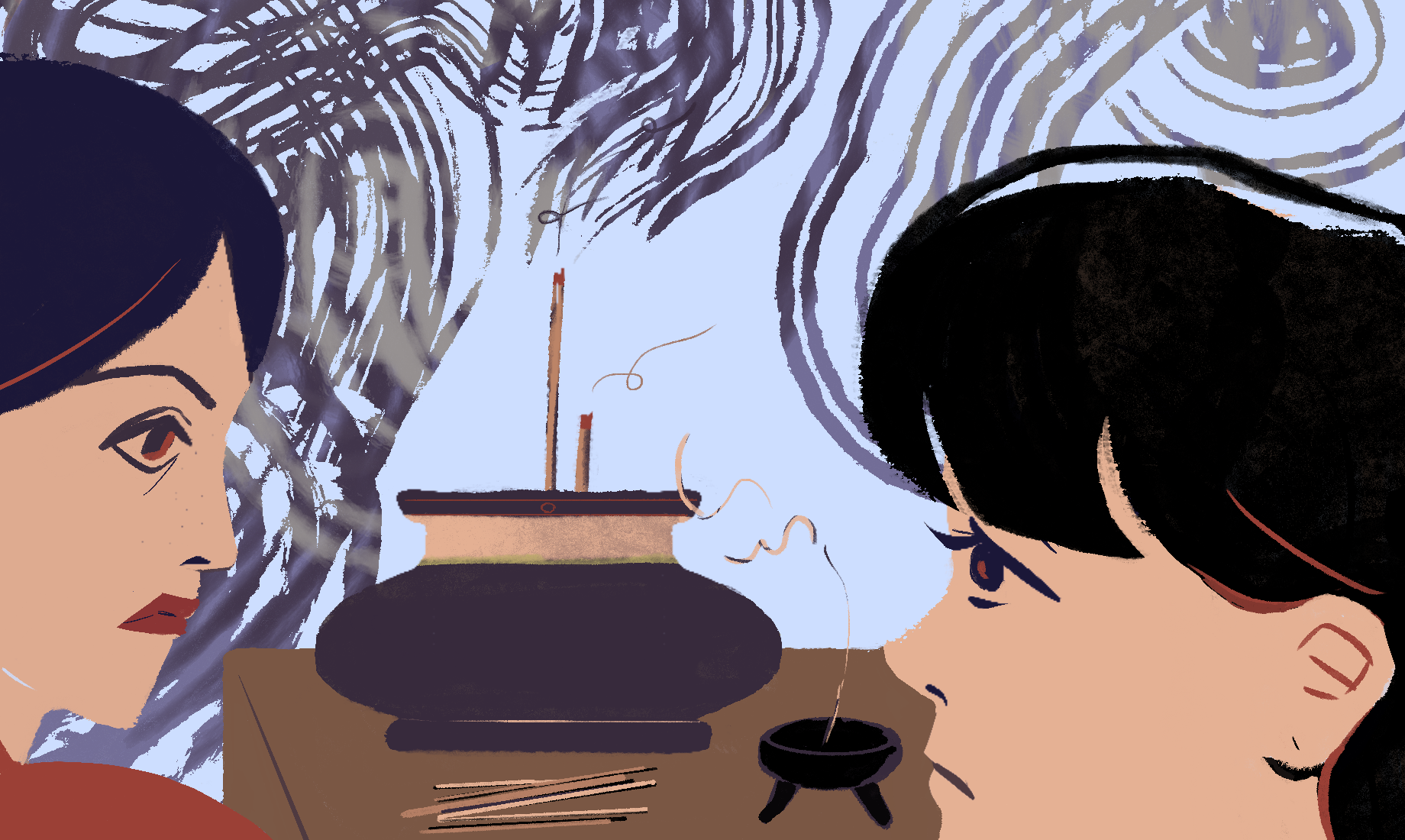

My mother is Chinese and my father is Scandanavian. Growing in Hong Kong, my mother taught me about traditional Chinese food, about paying respects to our ancestors by burning incense, and how to speak Cantonese, in order to pass on my Chinese heritage to me. But her teachings would also include the harsh words she’d say, her controlling behaviour, and attempts to mould me into the perfect Chinese daughter. She would justify it by saying that it was all a part of Chinese culture.

“Her teachings would also include the harsh words she’d say, her controlling behaviour, and attempts to mould me into the perfect Chinese daughter”

I thought her actions were tough love or just ‘a bit mean’, but abuse wasn’t something that crossed my mind. I grew up thinking this behaviour was acceptable because I was taught that Asian parents are tough on their children, that her actions are merely that of a loving mother with a different cultural perspective to my own. Every time I’d ‘fight back’ and defend myself from her cruel words, she told me that she’s Chinese and that being raised with more Western sensibilities by my white father meant I simply didn’t understand how a Chinese mother treated her children. But no one, regardless of their cultural upbringing, should call their child “stupid”, “lazy”, “fat” or a “waste of space” out of ‘love’.

She exerted financial and emotional control over me by offering money to help with rent and bills only if I did what she wanted: stop pursuing journalism, stop spending time with my friends or boyfriend , and move back home with her. As a good Chinese daughter, I was told to respect, love and obey her no matter what, just like my mother was taught to obey her parents. But I never really agreed with this sentiment; I believe that people, even family members, should continually earn your love and respect.

Unsurprisingly, all of this made me suppress and shy away from any interest in Chinese culture, removing myself from that side of my mixed race identity because I associated it with abusive behaviour. I’d never want to treat any friend, family member, or my future children that way, so I buried this facet of myself to protect myself and others around me.

“All of this made me suppress and shy away from any interest in Chinese culture, removing myself from that side of my mixed race identity”

But, in recent months, I’ve been coming to terms with the fact that our shared cultural background doesn’t excuse or mitigate her abusive behaviour. Abuse can happen in any cultural context or situation, and Chinese culture does not prescribe it in any way, shape, or form – there are plenty of Asian families who are loving and don’t emotionally abuse their children while still adhering to their traditional values. I see my East and South Asian friends with their parents, each of them practicing their culture, traditions and religions in different ways. And while they may have varied perspectives on life, their parents would never speak to them the way my mother speaks to me.

There are so many beautiful aspects of Chinese culture, many of them I have slowly started to rediscover recently. I now celebrate Lunar New Year and Mid-Autumn Festival in my own way without fail each year. I’ve started watching Chinese TV shows, which used to remind me of my mum, but now helps me brush up on my language skills. I miss Hong Kong, and am looking forward to visiting again without seeing my mother so I can enjoy the city the way I’ve always wanted to since I left.

“By separating myself from my mother, I know I don’t have to separate from my heritage”

I’m not in touch with other members of my family, but I’ve reconnected with my old friends over the phone, whom I can speak Chinese to and share our cultural traditions, and I’m looking forward to immersing myself within London’s Chinese community once lockdown is over. I’ve missed out on so much in removing myself from Chinese culture entirely, and don’t have a full understanding of myself or where I come from, all because my mother led me to believe that culture and abuse were intrinsically linked. I now understand they’re not.

With the support of my friends and my therapist, I’m making strides to cut contact with my mother and live my life without her abuse. While some would suggest imposing boundaries or limiting contact, I’ve tried it all before and my mother is a very ‘all-or-nothing’ kind of person, so unfortunately, cutting ties is my only option. By separating myself from my mother, I know I don’t have to separate from my heritage, from the aspects of Chinese culture that I love, and from who I am. When I find the strength to finally do so, I’ll no longer let her hide behind the excuse of Chinese culture to exert control over me and say cruel things.

The writer’s name has been anonymised to protect their identity.