Canva

‘Some of us never allow whiteness into our throats, some of us code-switch’ – how our voices shape us

In an extract from Nadia Owusu's forthcoming memoir, Aftershocks, the author explains the way our voices and accents can determine our identity.

Nadia Owusu and Editors

03 Feb 2021

As far as I know, only one home movie exists of me as a child. To my ears, the voice in it, but for the accent, is clearly mine – the pitch, the tone, the timbre, the too-long pauses between thoughts. Yet when I was in my mid-twenties and I showed the video to my then-boyfriend George, he exclaimed, “I can’t believe that’s you.” His eyebrows rose into sharp mountain peaks. He couldn’t get past the fact that the voice coming out of the mouth of the six-year-old version of me-the bony, bespectacled girl wearing the green pinafore and red knee socks of my school uniform-was British.

My British voice was quite posh but with the North West London tick of saying yeah with an implied question mark after nearly every sentence: “Auntie Harriet’s not here, yeah? She’s on night shifts.” “My dad’s in Bangladesh, yeah? He’ll pick me up in August.”

George only knew my current, standard American voice – the one that has more than once been described as sounding like an evening news anchor’s; a white American evening news anchor’s.

***

After my mother left, my father tried for a time to take care of my sister Yasmeen and me on his own. But he had to travel a great deal and didn’t want to leave us with nannies. So when I was three and Yasmeen was two, we were sent to live with our aunt Harriet in Hailsham, England. We lived in Hailsham for two and a half years, until my father and his girlfriend Anabel got engaged.

Of my time in Hailsham, I remember that I was one of very few black children at the private school in town. And for some reason unknown to me perhaps an administrative glitch, uncorrected – I was the only girl in my class. I remember that we called our next-door neighbours Auntie Lily and Uncle Ernie. They were a kind retired white couple with fluffy grey hair and a beautiful garden of pink and yellow roses. They babysat for my cousin Laura, Yasmeen, and me when Auntie Harriet worked night shifts.

Auntie Lily read to us and Uncle Ernie taught us to tend to the roses. The man who owned a local Chinese restaurant also babysat for us sometimes. We called him Uncle Chang. Chang was his last name. I cannot remember his first. He let us eat all the noodles and dumplings we wanted. He sounded British, not Chinese. He was both. Once, I asked him if he spoke Chinese. He did, he said, and offered to teach me. I said yes, but I was only being polite. Speaking Chinese would make me stand out. I already knew it was best, in some places and with some people, to conceal rather than to cultivate my vocal complications. I remember that everyone at school liked the boy with Pakistani parents whose name was Neil. He didn’t have a Pakistani accent. I remember some of his friends making fun of the Indian man who owned the sweet shop near school. He wore a turban and turned his v’s into w’s.

“Race matters in England. So too does class. So too does voice.”

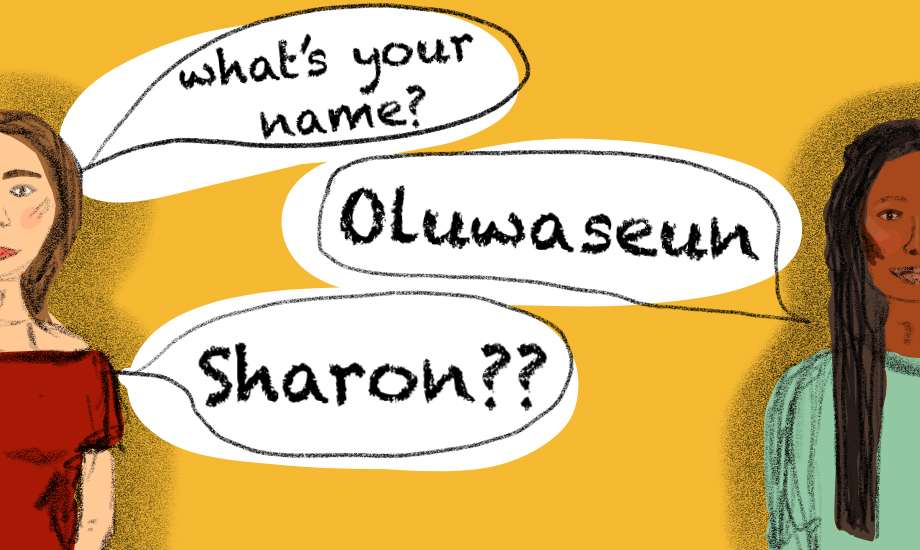

Race matters in England. So too does class. So too does voice. My race was what it was. It could not be changed. Class was not something I intellectually understood yet. But I understood there were “right” voices and “wrong” voices. I understood this had something to do with the value of whiteness and also of houses. People who lived in the biggest houses were said to be posh, and their voices were to be respected and minded.

I remember imitating the voice of my best friend Jenny. We were in the same after-school ballet program, and although we were in different classrooms at school, we were in the same year, so we found each other in the playground at morning break and in the cafeteria at lunch. She had long, curly blondish hair and rosy red cheeks. Mornings, she was often dropped off by both her parents. They would each hold one of her hands and swing her forward and backward as she squealed with delight. I saw the way they looked at Jenny. I saw the way other adults looked at Jenny: like she was something precious. “She’s a proper English rose,” one teacher said. I wanted to be loved like Jenny.

I understood enough about England to know I would never be a proper English rose. White English people could say they were English, but black and brown people called themselves British, even if they were born and raised in England, even if their parents and their parents’ parents were born and raised in England. I asked Auntie Harriet why that was. She said, “Because black people aren’t English,” which wasn’t an answer, but the finality in her voice told me it was all I was going to get.

But if I couldn’t be a rose, perhaps I could be some other type of equally charming flower. Jenny had a bit of a lisp and bad year-round allergies. She sounded like her nose was blocked. I tried on the lisp and the blocked nose, but when my father came to visit, he told Auntie Harriet she should take me to a doctor to see why I was lisping. “Maybe something’s going on with her teeth,” he said. I didn’t like doctors. I dropped the lisp stat.

“We can speak in the voice of whiteness if we so choose. Some of us know no other voice. It was born in us. It is the voice colonisation left us”

When I was five, we moved in with my father and Anabel in Rome. By the time I was seven, I spoke fluent Italian. By age nine, I was also conversant in French (language immersion classes twice a week after school) and able to get the gist of eavesdropped family gossip in Swahili (Tanzanian stepmother).

As we moved from Europe to Africa and back again, my accent zigzagged between British and the hard-to-codify accent of children who attend international schools. The yeah/question mark was copied from my cousins (the children of my father’s three sisters who all eventually planted roots in London). I spent many Christmas and summer holidays with them in Kingsbury, a working-class neighbourhood in North West London that is predominantly West African, Caribbean, and East Asian. It is a neighbourhood populated by people with fault zone voices.

The people I knew in Kingsbury, my family included, switched back and forth between proper English at work and something more cockney-leaning among friends. They spoke a few words of Urdu to the halal butcher and nodded ‘All right?’ to the Liverpudlian man who owned the fish and chip shop; Nigerian pidgin was for the cab river and Jamaican slang for the Rastafarian family who lived next door.

As I talked, I noticed that my friends’ eyes widened with confusion or squinted with suspicion. Once, I complained extravagantly that someone had taken a piss in the elevator, and my friend Ernest told me to get over myself. He asked if I thought I was better than him. I did not think I thought that, but I was abashed by the question. My solution was not to examine my entitlement and insensitivity but rather to hide from scrutiny. When I met new playmates, I neglected to mention I was visiting for the summer, that I lived in Italy. I told white lies. I claimed my cousin Laura’s school as my own. I started saying innit instead of isn’t it. I started saying yeah/question mark.

***

People of colour know that not all of the safety and spoils of whiteness are available to us. Yet we can speak in the voice of whiteness if we so choose. Some of us know no other voice. It was born in us. It is the voice colonisation left us. Some of us adopt it later-in childhood or early adulthood-and lose our other voices. Some of us never allow whiteness into our throats. Some of us code-switch. I am a code switcher.

This edited extract was taken from Aftershocks: Dispatches from the Frontlines of Identity, published by Sceptre on 4th February 2021. Pre-order now.

Nadia Owusu is the Whiting Award-winning author of Aftershocks. By day, she is the director of storytelling at Frontline Solutions, a black-owned consulting firm that helps social-change organisations to define goals, execute plans, and evaluate impact. Follow her on Twitter @NadiaOwusu1 and Insta @wheresnadia.