Diyora Shadijanova

Like Yewande, I’ve had enough of people mispronouncing my name on purpose

Oluwaseun Matiluko

26 Jan 2021

My name is Oluwaseun (“O-LU-WA-SHÉ-UN”). In the Yoruba language, it means ‘thank you God’ or ‘we give thanks to God’. My parents were thankful for my birth and hoped that I would be a blessing unto others. That when I walked into a room, people would not curse me, but instead be thankful that I was there. Yet, growing up, I wasn’t very thankful for my name. I was made to feel like it was more of a burden than a blessing.

Reality TV star and scientist, Yewande Biala, recently explained that when people refuse to call you by your given name, it’s an act of “racialised renaming”. Her words resonated with many, including me.

Back in the early 2000s, before the pandemic, teachers would sit in swivel chairs in front of a computer and read off names from the register one by one.

“Anna?”

“Yes Miss.”

“Emma?”

“Yes Miss.”

“Michael?”

“Yeah.”

Then a pause. A long pause. The teacher would hesitate, turn around in her swivel chair and look straight at me, because invariably, I would be the only black person in the classroom. She’d say with a grim smile on her face, “I’m sorry, I can’t pronounce this name.” The worst was when they got a little passive aggressive with it, and said “Oh my goodness, your name is so beautiful but…can I call you something else?”

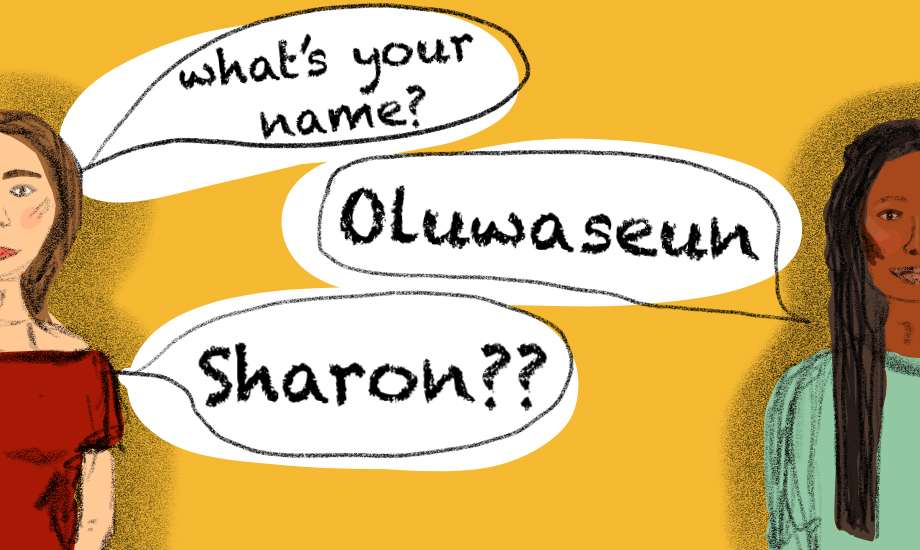

In the early days when this would happen I would smile right back and say my name confidently – Seun. But the teacher still wouldn’t get it. And we’d go back and forth, forth and back. Seun. Sharon? Seun. Shoe-un? Seun. And they still wouldn’t get it. Some would sigh, others would roll their eyes and still more would mutter under their breath that they didn’t get why my parents had given me such a “ridiculous name”.

“Some would sigh, others would roll their eyes and still more would mutter under their breath that they didn’t get why my parents had given me such a ‘ridiculous name'”

Whenever we had a new teacher, from primary right through to university, classmates would giggle as they knew my name was coming up next on the register, while I squirmed on the inside. In fact I still remember an awards ceremony at university, where another black girl said: “I can’t wait to see them struggle with your name”, before laughing while again, I squirmed.

I hated my name for a good while because no-one could pronounce it, and indeed because no-one could pronounce it, my identity has gone through many permutations over the years. At one primary school I was called ‘Shaun’- because according to my teachers back then ‘Seun is pronounced Shaun in Irish’ (I’ve since confirmed with actual Irish people that this is not the case).

At another I was called ‘Show-un’ and I decided to stick with that for a while, and took it with me to secondary. After all, it was easier to explain to white people. In a cadence not unlike how Jedward would say: “My name’s John and his name’s Edward and together we are Jedward”, I would say: “It’s like you put on a show, and then the French for number 1 is ‘un’- so my name is Show-un.”

Then at university I met another Seun who had anglicised their name to ‘Shay-un’ and so soon I became ‘Shay-un’ too. In sum, I was Seun, but other people knew me as Sean, Show-un and Shay-un. It’s kind of like Beyoncé with Sasha Fierce, but less empowering.

It was a shame this was the way things were, because in Yoruba culture, your name is extremely important. Typically, we have a naming ceremony when the child is eight days old, where many family members come and pick a name for the child. We don’t give our children random names like ‘Apple’ but instead put real thought into what type of people we hope they will be in the world.

“It took me a long time to understand this, to understand the beauty in my heritage and the prophecy in my name”

We have kept up with this tradition, notwithstanding the fact that the British started making headway in colonising our part of the world in the 1900s, and managed to annex the majority of us in a country they called Nigeria in 1914. Notwithstanding the fact that the politicians who facilitated our colonisation thought that black Africans “might be called savage people” and that Lord Lugard, Nigeria’s first colonial governor, described the “typical African” as a “happy, thriftless, excitable person, lacking in self-control” we continued on with our traditions and ensured that the spirit of our people would never die.

And it took me a long time to understand this, to understand the beauty in my heritage and the prophecy in my name. But as I approached my final years of university I met more and more people of West African, East African, Southern African and South Asian heritage who took pride in their name and their background and I began to realise that my name is something to be proud of. Regardless of the fact that people continue to mispronounce my name and laugh at it today I now know that there is power in my name.

The name Oluwaseun means Thank You God and the name Yewande means Mother Has Returned. And these names are beautiful and deserve the dignity of being pronounced correctly.