Hayfaa Chalabi

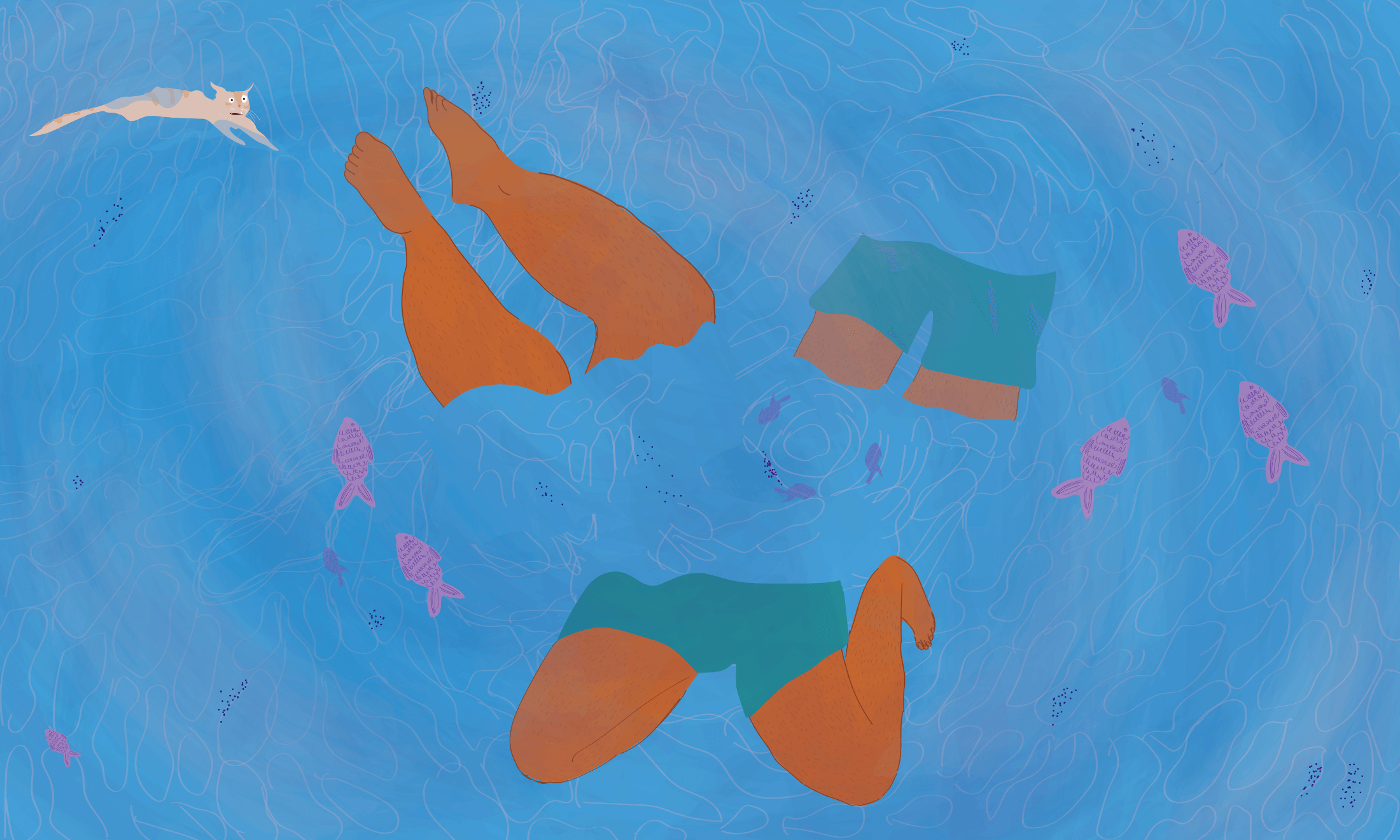

Navigating the seas: Why Muslim women’s swimwear doesn’t define our faith

Imbued with issues of modesty and body autonomy, swimwear is far too contentious a topic among Muslim women.

Hafsa Lodi

14 Jul 2021

I never thought I’d wear a burkini. I felt so strongly about this that, in my book Modesty: A Fashion Paradox, I vowed to “never wear one myself”. But in the two and a half years since pledging that on paper, my thoughts on swimwear have become more fluid, and I now appreciate the comfort and protection that full-coverage swimsuits can provide. My views on swimwear, and on modesty, are constantly in flux – especially after becoming pregnant and giving birth, and immersing myself in the world of modest fashion while forming my own, ever-changing interpretations on what that entails.

I now own two different burkini tunics, but I don’t wear them because I believe it’s religiously mandated to cover your skin. I simply find them comfortable and like the elegance they exude – they also save me the hassle of putting sunscreen on my back.

I decided to wear one of these – a design by Italian modest swimwear brand Munamer – on a recent staycation with friends. From afar, it appears to be a bedazzled mini dress, emblazoned with pearls and crystals. Up close, it becomes clear that it is in fact a printed swim tunic, with long sleeves, a high neckline and hemline that reaches the thighs. The unique burkini design comes with matching black leggings and a hood, which I’ve opted not to wear. As I put my towel down on a lounge chair and enter the swimming pool, my fellow Muslim friends are in awe that what I’m wearing is actually a swimsuit, and they “ooh” and “aah”, congratulating me on my increased show of modesty. Yet these comments immediately make me feel uncomfortable about the attention on my body and attire, and I’m wary of hyper-focusing on the amount of skin I’m covering.

“I don’t believe that you must cover the entirety of your arms and legs in order to be a ‘good Muslim'”

Though my opinion might be an unpopular one among a group of fashion conscious friends – who are inclined to gossip yet are adherent to orthodox Muslim and traditional, often-patriarchal, South Asian beliefs about women’s bodies – here it is anyway: I don’t believe that you must cover the entirety of your arms and legs in order to be a ‘good Muslim’. Nor do I believe that burkinis are the only swimwear silhouettes ‘permissible’ for us.

Yet many Muslim women I know are adamant on covering up to their wrists and ankles (even if they don’t identify as “hijabi”), in a bid to dispel any doubt about their “Muslimness”. Many avoid outdoor beach and pool activities, sidestepping the swimwear dilemma altogether. Some find mixed-gender pool and beach outings to be awkward, while for others, the hesitancy stems from deeper-rooted insecurities – such as keeping the roving eyes of their husbands in check, lest they view their female friends in swimsuits.

I’m a practicing Muslim who enjoys regular, mixed-gender trips to public pools and beaches. Growing up as a teen, I thought I was “too covered” among my non-Muslim peers – I couldn’t help feeling insecure in my unstylish, sporty one-pieces while my friends wore feminine bikinis. Now, as an adult, I often feel “too exposed” within my friends’ circle of fellow Muslim women, who favour full-coverage burkinis over my comparatively bare swimwear.

“We ourselves sexualise and ostracise women who don’t conform to our own modesty standards”

I’ve always felt comfortable wearing one-piece swimsuits with shorts, and by my own standards, the resulting look is modest enough. Many of my friends, however, will look at a swimsuit-clad Muslim woman with incredulity and sometimes even question the parameters of her faith and adherence to Islam if she chooses to reveal so much skin. Ironic, isn’t it? Proponents of modest fashion claim covering up emancipates women from being sexualised, yet we ourselves sexualise and ostracise women who don’t conform to our own modesty standards – standards that have been dictated by ancient patriarchs’ interpretations of religious texts and traditions, and passed down over generations.

Our community – Muslim South Asian, with heavy Middle Eastern influences – is one where your choice of swimwear can quickly determine which “camp” of the faithful you belong in: the ultra-modern liberals or the conservative, proper, “practicing” Muslims. But attributing one’s religious adherence to their style of swimwear is indicative of a narrow-minded lens that many of us are culturally conditioned to see through, when we should be placing value on inner virtues and focusing on our own spiritual growth instead.

For many people, the subject of swimwear is often riddled with anxieties, irrespective of faith or culture. Questions of comfort, body complexes and self-image already swirl around in our heads when we’re shopping for swimsuits, and among Muslim women, the dilemmas are only amplified due to community members’ tendencies to judge and police our bodies. Outsiders claim we cover up too much, provoking burkini bans in some European towns, while some insiders will nit-pick the skin-tight and skin-revealing nature of swimsuits, sometimes even deeming even full-coverage burkinis to be “immodest.”

“Swimwear shaming – an extension of fashion policing – undermines our basic rights to body autonomy and human dignity”

In Ruqaiya Haris’ essay on modesty in the age of social media, which features in Cut from the Same Cloth, a new anthology of writing by Muslim women, she says: “One woman’s turban hijab is another woman’s not-quite-authentic-hijab; one woman’s modest fashion ensemble is another woman’s immodest fashion ensemble.” The same rings true in the realm of swimwear. While some wear burkinis, others might wear bikinis – like American model Maryam Basir, who in 2013 told CNN that she is practicing Muslim, prays five times a day and occasionally models bikinis. “It doesn’t make me any less faithful,” she said in the interview, adding that only God, and no person, could judge her.

Swimwear shaming – an extension of fashion policing – undermines our basic rights to body autonomy and human dignity. No matter what the religious texts may say about modesty, they are open to interpretation, and can be held against Verse 2:256 of the Qur’an, which states, “there is no compulsion in religion.”

Today, the market is flourishing with options thanks to the global modest fashion boom, from Nike’s Victory Swim collection to the new full-coverage swimsuits by Adidas. Many smaller, independent brands like Munamer, Maya Swimwear, Lyra Swimwear, Sei Sorelle and more. And while it’s great to have a range of choices for Muslim women, those like me, who may choose to only partially cover our bodies or change our swimwear depending on our moods, often feel left out of the modesty narrative. Modesty after all, is an ever-evolving journey, with diverse interpretations and embodiments, yet making burkinis synonymous with “modest swimwear” can homogenise this retail category, thereby implying that swimsuits that aren’t full-coverage, aren’t modest or Muslim-friendly. We should celebrate the influx of modest swimwear brands in the market, but we should also respect and embrace each Muslim woman’s right to choose what to wear to the beach or pool, even if it doesn’t reflect our own culture-bound “modesty” guidelines.

Unfortunately, some parts of the community at large remain fixated on the concealing of women’s bodies, and while we may not be able to resolve this deeply-rooted modesty hysteria, we can strengthen our own armour – modest or otherwise – to develop thicker skin. Never will our style preferences conform with everybody else’s picture of ‘the perfect Muslim woman’ and the sooner we accept this and mentally detach from societal pressures, the sooner we’ll find peace with ourselves and our swimsuits – whether they’re surf-inspired burkinis or string bikinis.