Sahar Ghorishi

A second Nowruz in lockdown is distancing me from my Persian culture

It’s hard to keep connected to your culture when you can’t celebrate its rituals.

Sahar Esfandiari and DiyoraShadijanova

19 Mar 2021

What connects ethnolinguistic groups across Iran, Kurdistan, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan and other regions in the Middle East and Central Asia? A 3,000-year-old celebration of the coming of spring called Nowruz. Usually observed on 21 March, it’s also commonly known as the Persian New Year.

With the outbreak of the pandemic, last year saw the last minute cancellation of Nowruz events and family gatherings, which made for a lonely time. It felt wrong to be celebrating anything in the context of what was happening in the world, yet there was a sense of hope that this sacrifice would mean an even bigger celebration the following year.

Today, one year on, the government’s frustrating mismanagement of the pandemic in the UK has meant another Nowruz in lockdown. The hope we felt last year has disappeared, naivety replaced with anger and mistrust towards the institutions whose responsibility it is to protect our communities.

One of the hardest changes of the last 12 months has been the feeling of detachment from my culture and identity, brought on by the physical limitations of the pandemic. I’m no longer able to joyfully practice traditions with my community and connect with my roots.

“One of the hardest changes of the last 12 months has been the feeling of detachment from my culture and identity, brought on by the physical limitations of the pandemic”

In the context of my own Iranian family, Nowruz is a time of family, food, and community. At the centre of celebrations is ‘Eid Didani’ – a tradition of visiting family members during the new year period and later hosting them back in return. As the tradition goes, younger members will visit their elders first out of respect, before elders pay back a visit.

For the two weeks around Nowruz, our front doors are revolving, welcoming guest after guest, day after day, with steaming black tea, the scent of hyacinth flowers in the air, plates of seasonal fruits, nuts, and special new year’s pastries filled with thick sweet cream. Pleasantries are exchanged and well wishes are made for the year ahead. Older members of the family gift money to younger members, sometimes laid between the pages of a Qur’an. Everyone is decked out head to toe in new clothes.

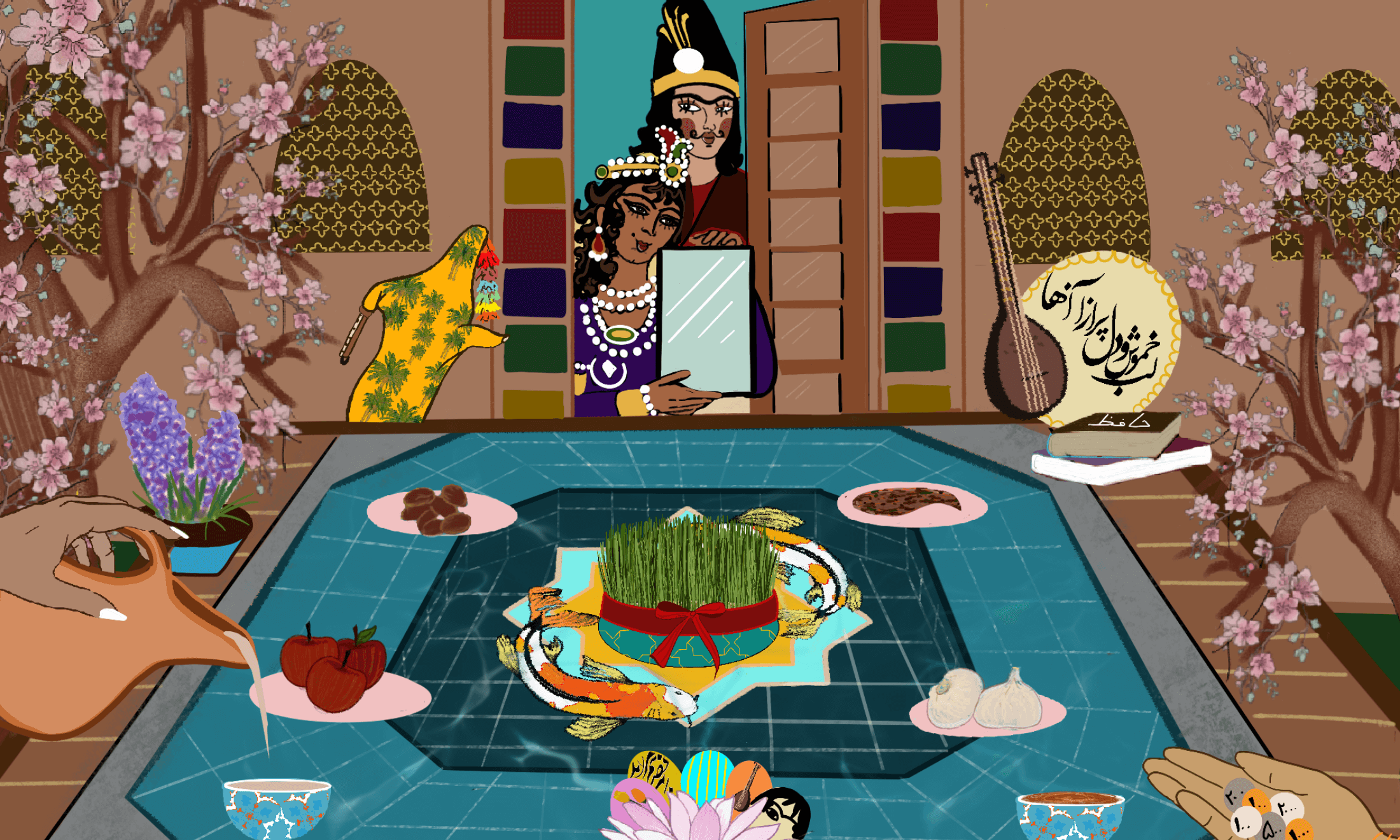

In the run-up to Nowruz, each household prepares a ‘Haft Sin’ table, a spread with seven items all starting with the letter S in Persian. An apple, ‘sib’ to represent beauty; coins, ‘sekkeh’ to symbolise wealth and prosperity, and garlic ‘seer’ representing health and medicine. Eggs are hollowed and decorated in bright colours by children to place alongside these items. Most households also include a copy of the Qur’an and the work of Hafez, the country’s most celebrated poet from the 14th century. Kitchens are bustling and the delicious smell of our traditional Nowruz lunch Sabzi Polo Mahi, a herb rice and fish dish, wafts through every home.

“For the two weeks around Nowruz, our front doors are revolving, welcoming guest after guest, day after day”

In London, some of the highlights of my year include going to poetry evenings and parties organised by the Iranian community to celebrate traditions like Shab-e-Yalda, Chaharshanbe Suri, and Nowruz. I’ve made some of my closest friends at these events and engaging with them cultivates feelings of feeling pride, inspiration, and interconnectedness. Community events give us the space to honour our histories and relax into our most authentic selves without judgement.

Growing up, my family’s yearly trip to Tehran from London formed the bedrock of how I understood and practiced my Iranain identity. Almost all of my wider family live in Iran and every year, as soon as I landed in Imam Khomeini Airport, I’d dance in the whirlwind of familiar people, smells and sounds. The sight of the Alborz mountains from our home and the perfect balance of sweet and sour in my grandmother’s cooking filled me with a contentment and joy that’s hard to replicate during the rest of the year. I’d always come back to the UK feeling grounded and whole.

“For diaspora communities at a physical distance from countries we call ‘home’, special celebrations like this leave you feeling melancholy”

For diaspora communities at a physical distance from countries we call ‘home’, special celebrations like this leave you feeling melancholy. This year I witnessed Iran suffer through one of the worst Covid-19 outbreaks in the world from afar, worried sick about family members I was unable to visit, not knowing when or if we’ll see each other again.

Unfortunately with travel restrictions stopping many of us from making trips home since last year, connecting to these aspects of my identity has left me feeling distant from my culture, and unable to access certain parts of myself. Realising this has reinforced to me the significance of actively honouring celebrations such as Nowruz more than ever, for the opportunity it gives to connect – both with aspects of ourselves but also with our communities. It has also made me conscious of my privilege for being able to travel to Iran and visit my family pre-Covid times, something denied to many people living in diaspora communities.

This year we’ll be unable to celebrate Nowruz in the usual way, but at its core the day is about new beginnings and hope. Despite our current realities, the trees are still blooming, the days are getting longer, and the weather is shifting into warmer temperatures, signalling the end of a harsh winter. Perhaps the best way to celebrate Nowruz this year is to connect with the spirit of optimism it signifies, and look forward to being able to safely see our families and loved ones again soon.