I’ve recently started intentionally neglecting the un-reciprocated emotional labour I so often perform on auto-pilot.

This labour includes remembering others’ schedules and reminding people around me of their own commitments and appointments; messaging friends to make sure they got home ok, and checking in on people who only get in touch when they need something from me. Ditto nodding along vapidly to mansplained/whitesplained lectures on topics I don’t care about, or smiling weakly at an unsolicited remark on my physical appearance, lest I make someone feel awkward.

I’ve taken inspiration from J-Lo’s song Ain’t Your Mama, which seems to be a battle cry against work that is predominantly performed by women and which typically goes unremunerated. These tasks include cooking “all day”, doing laundry, and ironically considering Dr Luke’s involvement in the track, “putting up with” sexual harassment in the workplace.

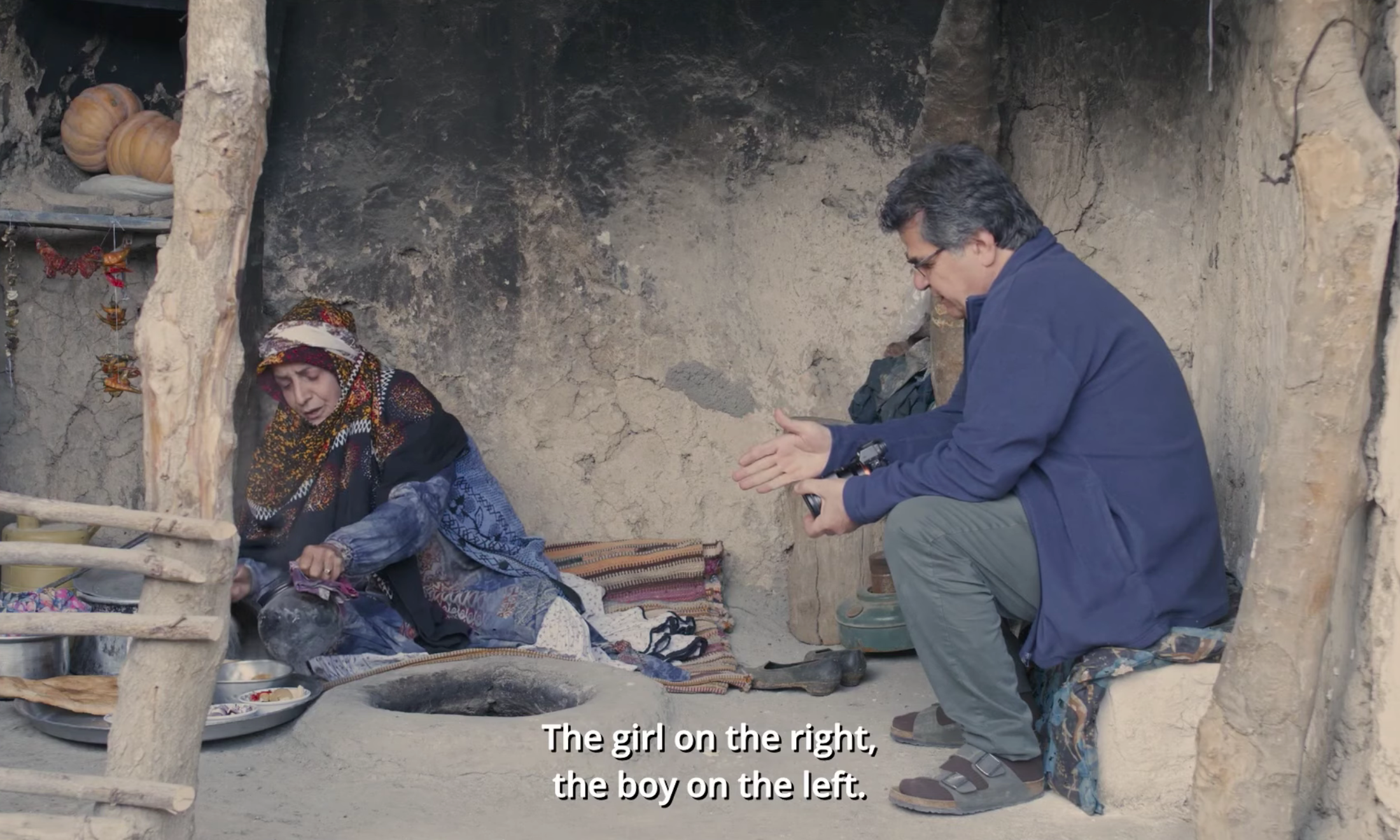

The second category of work illustrated in the video for Ain’t Your Mama is womens’ constant provision of a smiling support service and ego-massage for partners, colleagues, family members, and even complete strangers. The song is a stirring pop anthem with a playful video which sees J-Lo don a series of fantastic outfits in a range of domestic, white and blue-collar workplace settings:

Feminist Silvia Federici wrote in 1975: “The unwaged condition of housework has been the most powerful weapon in reinforcing the common assumption that housework is not work, thus preventing women from struggling against it […] We are seen as nagging bitches, not workers in struggle.”

41 years later, women now make up 47 percent of the UK workforce and despite the entry of women into “professional” roles, women in Britain still perform at least two-thirds of unpaid housework.

The idea that housework and emotional work are not really “work” and therefore not worthy of respect or payment, runs deep. Glossy magazines and Hollywood films tell us that baking cupcakes, knitting clothing and helping our male friends with their romantic problems are things women do “for fun” in their leisure time. For some, they are. But why is it that traditionally “male” unpaid labour such as mowing the lawn, washing the car, and painting and repairing the living environment are, these days, commonly outsourced? Did someone decide that these tasks are too much like hard work?

The pressure to perform emotional labour is further intensified for women of colour, who experience specific stereotyping as being “sassy”, “blunt”, “angry” or “hostile”: simply for being non-compliant with a broad panoply of mens’ requests (“give us a smile!”), and calling out the double-pronged intersection of misogyny and racism we experience on a daily basis.

This service has been described for decades variously as “worry work”,”emotional management” or “emotional labour”. As Miri cites in their extremely comprehensive piece for The Orbit: “We are told frequently that women are more intuitive, more empathetic, more innately willing and able to offer succour and advice.”

Miri hastens to add that: “Like all gendered dynamics, of course, this isn’t exclusive to male-female interactions and the imbalance doesn’t always go in the same direction.”

Emotional labour exists on a vast spectrum which includes being a “shoulder to cry on” – even more draining if frequently unreciprocated – as well as performing work that is verging on secretarial: helping others manage and organise their lives, because you’re just “naturally good at it”. All unpaid.

Emotional labour is often invisible. It includes things that other people likely do not consider to be work, perhaps because they assume that these things happen “organically”. Things like finding yourself hosting at a social gathering you didn’t instigate, or gently corralling a bunch of friends from A to B because you took time to look up the route in advance.

Good organisation and communication are (largely) learnable skills, and women have only become disproportionately good at them because these attributes are expected of us from a young age.

Jess Zimmerman puts it plainly: “Housework is not work. Sex work is not work. Emotional work is not work. Why? Because they don’t take effort? No, because women are supposed to provide them uncompensated, out of the goodness of our hearts.”

Well, I’m afraid goodness is dead, so share the load or pay up. We ain’t your mama.