Tinuke Fagborun

Overpoliced and adultified: how the justice system is failing autistic Black people

Recent cases of police mistreatment have exposed the dangers autistic and neurodiverse Black people face in the UK. Campaigners are now calling for nationwide reform.

Riann Phillip

14 Sep 2022

Content warning: This article contains mentions of racism.

In 2018, 22-year-old Osime Brown’s life changed forever. Convicted of allegedly stealing a mobile phone, Brown spent two and a half years in prison, during which his family says he was racially abused and mistreated with a complete disregard for his disabilities.

While in prison, he received a letter from the Home Office stating that he would be deported to Jamaica where he was born, even though he has no family or semblance of a life there, and has lived in the UK since he was four. Thanks to a public petition that received nearly 430,000 signatures, Brown was not deported, but the fight to clear his name continues on.

Brown’s experience typifies the harsh reality of what it means to be Black and autistic in the UK. “My son has been shaped by the system to cut ties with his parents, be cut off from the system, and to be told the UK does not want him here,” Joan Martin, Brown’s mother, tells gal-dem. “The system failed our son.”

Like many other young Black neurodiverse people, Brown was not diagnosed with autism until the late age of 16. “When assessed and diagnosed, [Brown’s] results were not given the attention that my son deserved,” Martin says. “The system isolated him, he was deemed a failure.” Those who are misdiagnosed or diagnosed later in life will often go years without the appropriate care and support they need – such as medication, educational adjustments, access to therapy or financial aid.

“The system failed our son”

Joan Martin

Black children are already overpoliced and adultified in settings that should be safe and nurturing, like schools and social services, and autistic and neurodiverse Black children are even more vulnerable. Research commissioned by the HM Inspectorate of Probation in June 2022 confirms that Black children are more likely to be adultified and therefore are “at a heightened risk of their safeguarding needs being unmet”. Increasingly, Black neurodiverse children are being treated with suspicion and presumed deviant due to these biases ingrained in law enforcement.

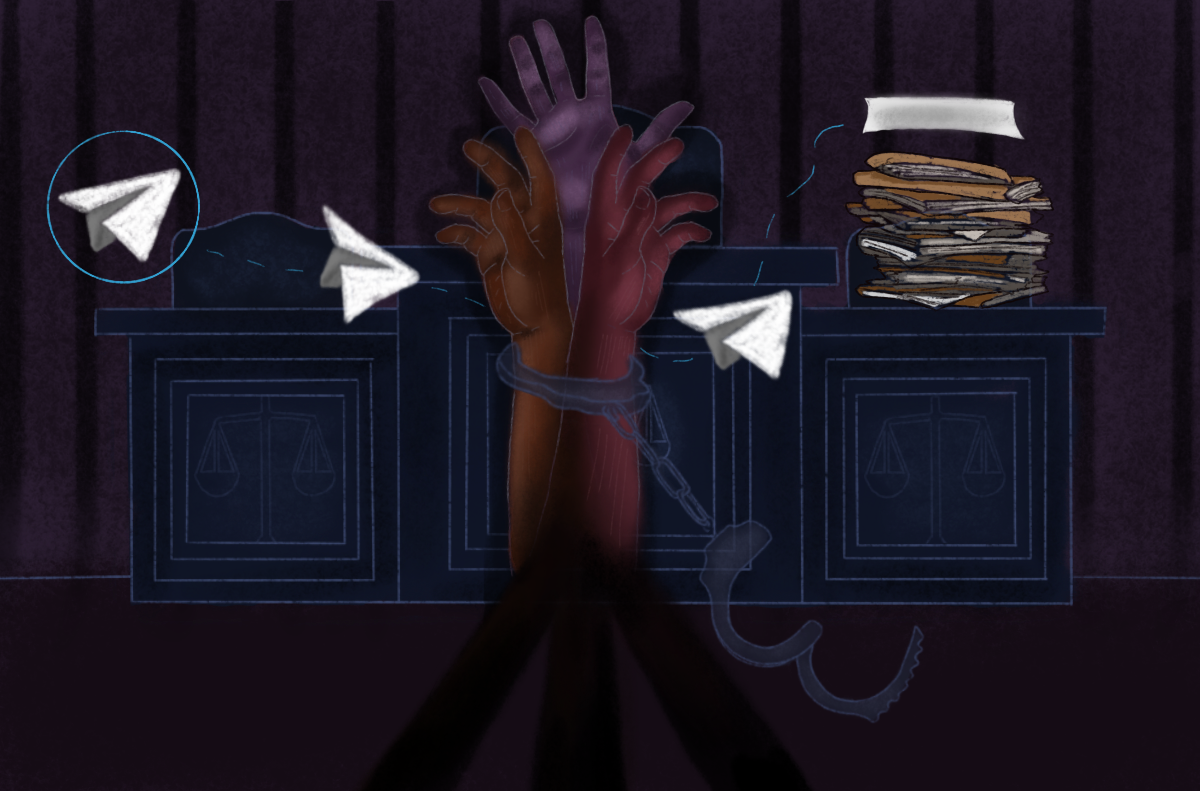

Brown’s case is just one example of young Black autistic people being failed by the police. In April, a 17-year-old Black non-verbal autistic boy from Kent was locked up in a facility in Gatwick airport to be deported to Nigeria. The boy, who is not Nigerian and has no connection to the country, had been reported missing by his family and was later arrested by the British Transport Police for alleged fare evasion. Because he had no identification and was unable to speak, he was detained at an immigration centre.

“They locked him up like a prisoner and mishandled him,” his sister wrote on Twitter. “When they saw my brother, they didn’t see a boy in pain, they saw his race.”

“Autistic Black teens or those that have mental health issues are immediately assumed to be a threat. It shouldn’t be that way,” says Emma Dalmayne, campaigner and member of Autistic Inclusive Meets. “The feeling of being safe is not there for our Black autistic teens.”

Just two weeks before the other incident at the immigration centre, Antwon, a 12-year-old Black autistic boy was attacked by a white woman with a boat paddle at a Bristol lake, after she accused him of “throwing stones”. Despite being a racist attack, the case was dropped by Avon and Somerset Police. They later u-turned after receiving mass public attention and were criticised for not investigating properly.

“The police are not adept at dealing with Black neurodiverse [people], given the way they’ve treated Black people suffering with mental health problems,” a spokesperson for Copwatch, a decentralised network of communities monitoring the police, tells gal-dem. “They took the abuser’s side because she was a white woman.”

“Black neurodiverse children are being treated with suspicion and presumed deviant due to biases ingrained in law enforcement”

Young Black neurodiverse people continue to be failed and vilified; from late diagnosis or misdiagnosis, lack of appropriate support from healthcare and education professionals, to a complete disregard for their wellbeing when affronted with law enforcement. Black people are four times more likely to be detained under the Mental Health Act 2019 than white people, and only 26% of research into autism considers race or ethnicity data at all.

Alex Raikes, from Stand Against Racism and Inequality (SARI), a charity that offers support to victims of hate crimes, says being both Black and neurodiverse “renders you even more at risk”.

“You are Black so you are still policed disproportionately, when they stop you and find some fault, you have to behave ‘better’ than your white counterparts,” he says. “If you’re neurodiverse, you might be less able to persuade the police or do necessary code switching.”

This problem seems to be getting more severe. As Raikes says, “the largest percentages of [SARI’s] clients are people of colour, even though we deal with all types of hate crime. But a larger and larger percentage of our clients recently have autism and Aspergers, or are disabled in some way.”

Changing the narrative

The effects of being a victim of the police do not end after the incident. Brown, despite being released from prison in October 2020 and free (for now) from the Home Office, continues to fight to overturn his conviction. He had been sentenced to five years in prison under the Joint Enterprise law, an experience that still stays with him. “He was mistreated. People who were supposed to help were rude to him and to us as his parents,” says Martin, adding that she and her son struggle with long-term illness related to the stress of the situation. “Osime is suffering from PTSD, physically damaged by his experience in prison, and the non-consensual over-prescription of medication, resulting in him suffering heart attacks and hospitalisation.”

Antwon will also have to live with the memories of being attacked for the rest of his life. “He was worried he had done something wrong, maybe it will hit him when he is older,” says Antwon’s father.

Joan is committed to fighting for her son and other people like Osime. She is currently setting up an organisation, Fobwell Spectrum, to help autistic people and their families overcome the difficulties like racism and ableism that are inherent in the social care and criminal justice systems. Joan says Fobwell Spectrum will “help autistic people, their families and guardians to fight back and overcome difficulties that the system presents and to change the narrative”.

Other campaign groups and activists are calling for a nationwide reform of policing to create safer spaces for neurodivergent and autistic people of colour. Dalmayne from Autistic Inclusive Meets says stop and search, the use of handcuffs in arrests, and brute force and aggression from police officers can be very intimidating for autistic and neurodivergent people. “They [the police] see a lack of eye contact, a hood up (to block out stimulation) as possibly trying to hide,” she says, explaining how her autistic son could react to being stopped by an officer. “They see a standoffish or less than sociable presence to be threatening.”

“Autism isn’t a disease. There needs to be more education and more promotional acceptance in the general public, in the police, in social services,” Dalmayne adds. “Not enough is known about autistic people. We’re not to be feared, we should be accepted and included.”

For more information, find your local Copwatch network and sign the petition to clear Osime Brown’s name.

Additional reporting by Priyanka Raval

Our groundbreaking journalism relies on the crucial support of a community of gal-dem members. We would not be able to continue to hold truth to power in this industry without them, and you can support us from £5 per month – less than a weekly coffee.

Our members get exclusive access to events, discounts from independent brands, newsletters from our editors, quarterly gifts, print magazines, and so much more!

Young Black men are being jailed over text messages

Inside the online forums where anti-Gypsy, Roma and Traveller sentiment thrives

Revealed: ‘Shocking’ number of asylum seeker infant deaths in Home Office housing