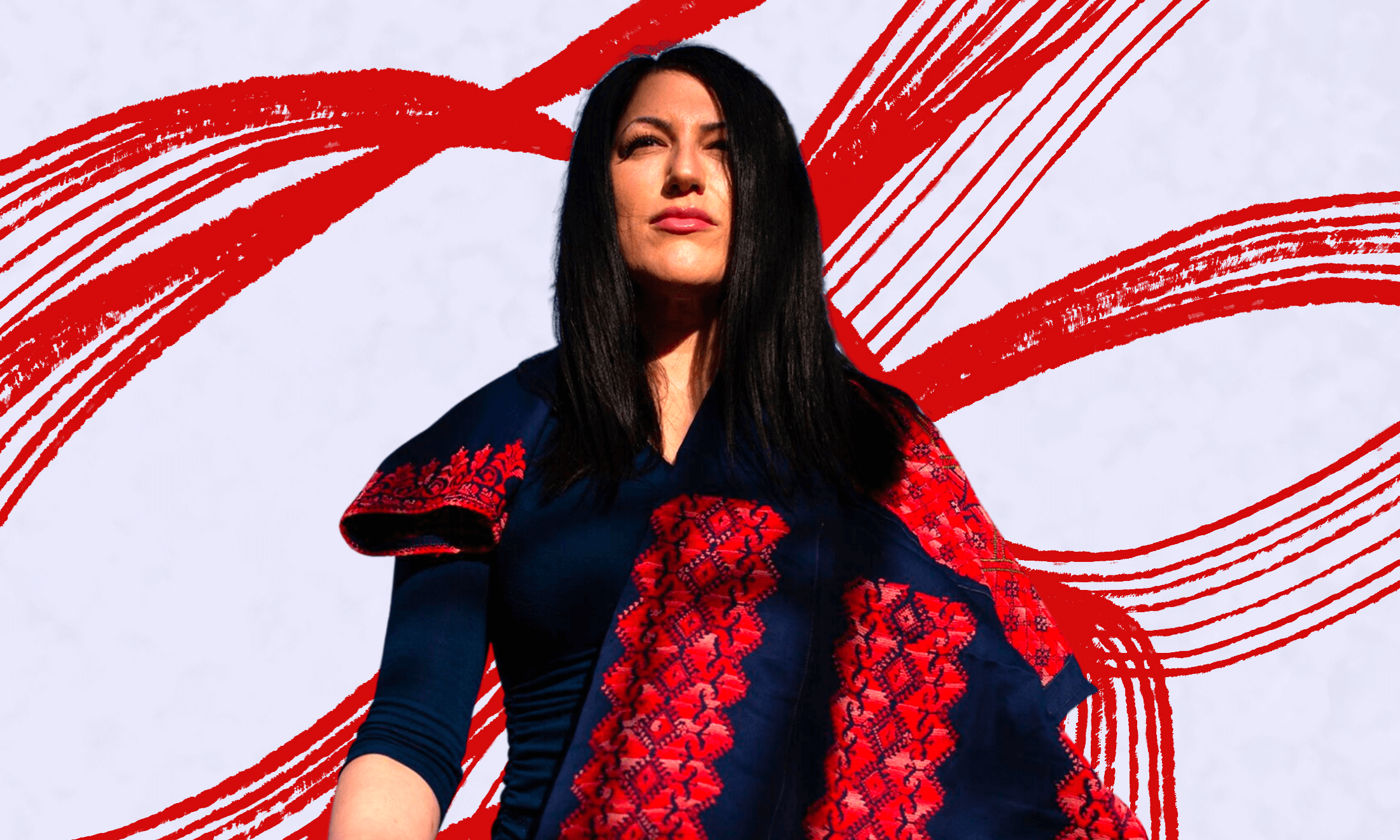

How one woman is keeping the politically charged and defiant art of Palestinian embroidery alive

The art of Tatreez embroidery has become a form of resistance for Palestinian women. Wafa Ghnaim is trying to keep the tradition vibrant in the diaspora.

Hadil Louz

14 Jun 2021

Carlos Khalil Guzman

Palestinian embroidery work, traditionally called tatreez in Arabic, has become a tool of resistance and a symbol of resilience for Palestinians. For Palestinian women in particular, the ancient art of tatreez has morphed into a powerful statement of identity since the 1948 Nakba that saw Palestinian territories occupied; where the art once used to symbolise life stages, such as pregnancy, for the wearer, it’s now an act of defiance.

When demonstrations of Palestinian nationalism were banned in the late 20th century, Palestinian women used tatreez to create the ‘intifada dress,’ which embroided the outline of the country and its flag. And displaced Palestinian women in refugee camps now produce the embroidery to earn an income.

For Palestinians in the diaspora, tatreez has just as much significance. Palestinian American Wafa Ghnaim is the founder of Tatreez & Tea, a project that seeks to keep the art alive outside of occupied Palestine, and bring Palestinian culture to the door of those who can support the nation’s liberation struggle. She sat down with gal-dem to tell us more about the power of a stitch.

gal-dem: Can you tell us what tatreez is?

Wafaa: Tatreez refers to all the various embroidery and stitching techniques of Palestine that have existed for centuries. We use a variety of stitches in our embroidery from all over Palestine. This kind of embroidery, in general, means stitching on your garments, and the ornamentation of cloth. Embroidery used to be an identifier for what village you were from [but] has [in recent history] become a national symbol of unity for Palestinians.

What is the story behind your Tatreez & Tea project? Why Tea? How are the early steps of this project going?

The name was meant for my 2018 book [also titled Tatreez and Tea].

In 2015, when I started writing my book, there was no online discussion about tatreez. It was non-existent. I wanted to bring tatreez back because I love it. This is something that my mother practiced and passed it on to me and my sisters.

Many Palestinians in exile do not know how to embroider. They are coming back to our art and culture to learn techniques about embroidery as a way of reviving it in the diaspora. I was trying to create a resource for them. It was not meant to be an authoritative text in a scholarly sense, but an oral history of my family.

Tea is a symbolic part of our storytelling traditions. It is the meaning and language behind our embroidery. When I was young and my mother would sit and teach embroidery to me and my sisters, she would make a pot of tea. While we were stitching, we would drink it, and she’d tell us stories about the meaning of embroidery. With Tatreez and Tea, I wanted to recreate the culture of stitching.

When did you start doing tatreez?

I cannot remember a time when embroidery was not a part of my life. My mother took a picture of me doing stitches when I was two. Tatreez was a part of my survival.

“We use the patterns themselves to tell a story”

Who is Feryal Abbasi-Ghnaim?

My mother is an artist. I call her an embroiderer artist. Palestinian embroiders are artists to me. When she graduated from college, she started teaching art and embroidery at refugee camps in Syria and Jordan, where she met my father. They got married and immigrated to the United States. Then she continued teaching embroidery as a way to express her culture and connect with her Palestinian identity.

I wrote the book to document all the stories, lectures, and the speeches she did about embroidery to the American public. She is an activist. When I was younger, I would wear thobe – the Palestinian national dress – to school. I was bullied a lot. I had gum spit in my hair. I dealt with a lot of prejudice in the United States for being Palestinian, being Arab, being different, having a mum with an accent, and having Muslim parents. In the 1980s and 1990s, there was no protection. And I grew up with this.

After I released the book, I started to receive a lot of interest from people who wanted [tatreez lessons]. This is when Tatreez and Tea was born, because of the desire to keep the tradition going, to preserve the practice and the history of embroidery.

Was your inspiration behind this project national, political, artistic, or all of those motivations?

There are many reasons why I do this work. Firstly, I am connecting Palestinians to their heritage. And I want to make this kind of art more accessible to them. It has been an endangered art form. Because I am in the United States, it is important to provide a way for people who support Palestinians to learn more about Palestine. In every one of my classes, I don’t just teach how to stitch but also teach the history of where the pattern came from and the history of Palestine.

“Part of resisting is making sure that we keep these traditions alive”

It became an important vehicle for me to combat the negative stereotypes, and the prejudice that exists, especially in the United States, towards Palestinians. And it allows me to have a proactive way, where I am sharing about Palestinian identity, outside of the news and outside of the events that are happening to Palestinians. I am actively fighting that by showing people that we are people; we create; we live; we have family; we have stories to tell; we create beautiful things, we cook; we teach; we laugh; we are you; we are humans.

I am working hard to incorporate history and scholarly research in my classes too. For instance, I taught how to [make] tatreez into kufyyah [traditional Palestinian scarf]. And I spent two classes talking about the history of the Palestinian kufyyah; what it represents and why it is so sacred. This kind of education is not offered in the university curriculums. Education is the way that you empower people to speak up when they see something that is wrong.

What kind of projects are you working on right now?

I am working on a thoub for my son who turned four this year. He said ‘I love pink’. So, for his birthday, in February, I did everything in pink. It is not a traditional thoub. I included unicorns to remind me of Melek and his fourth birthday. So, I am finishing that one. I am also working on a chest design for a thoub, and a denim jacket; then I will be working on another kind of mural, also pink. I’m starting new projects this summer with my students [as well], such as a map.

How can a life story be told through tatreez?

We use the patterns themselves to tell a story. So sometimes the patterns will represent the village, but they also have actual meanings. So, for instance, the ‘tree of life’ pattern. My mother calls it the ‘tree of life’, but most people call it a cypress tree that represents celebration and connection to land. Also, you can include stars and moon motifs, historical motifs, and educational motifs.

There are also colours that you use. We don’t have colours that represent specific things necessarily, but colours can tell a story too. For example, you heard my story [about] why I decided to select pink [for my son’s thoub], because [he loves] pink, and I wanted to celebrate his interest in it. But historically, Palestinian women use two colors to express themselves. So, it was a place of creativity and personal expression.

“When I embroider, I feel close to my homeland.” These were the words of your mother on your website, was that your main goal behind this project too? Does it make you feel closer to home while being in diaspora away from your real home? Does this spiritual feeling enhance or promote the sense of solidarity, belonging and identity?

Yes, I think you put it very perfectly. It is one thing to feel connected spiritually. But I think we have to translate that into action, especially now. My purpose in life is to share with the world what it means to be a Palestinian, and that we are not just numbers; we are not just a problem; we are not just a conflict or whatever the words they want to use; we are everywhere; and we are not going anywhere; we are here. And we are going to continue to resist. Part of resisting is making sure that we keep these traditions alive.

So that one day, when we return to Palestine, and we can come together again, even if it is in 100 years, our children’s children [will] have these tools that have been so important to Palestinians throughout the centuries. I feel like [the project] is my small thing that I’m contributing to the future of the Palestinian people.

Only by abolishing colonialism will Palestine be free

Shireen Abu Akleh: the voice of Palestine who refused to be silenced

Turns out the West understands boycotts, sanctions and divestment when it comes to Russia