Canva

This new postcode tool reveals how your local environment could be making you sick

Centric Lab's new 'Right to Know' tool uses postcodes to bring together data about the environment and deprivation.

Guppi Bola

27 Oct 2021

By now we know that environmental justice organising is more than just shitting ourselves about how greenhouse gases are heating the planet. And one massively important aspect of environmental justice in 2021 is the work to address how extraction and exploitation of the world and our bodies is directly connected to our health. It’s not just the earth that’s dying; the climate crisis also results in illness and death, predominantly in the multi-ethnic working class. This is how the term “environmental racism” emerged – in response to the ongoing systemic harm from the politics of the natural and built environment.

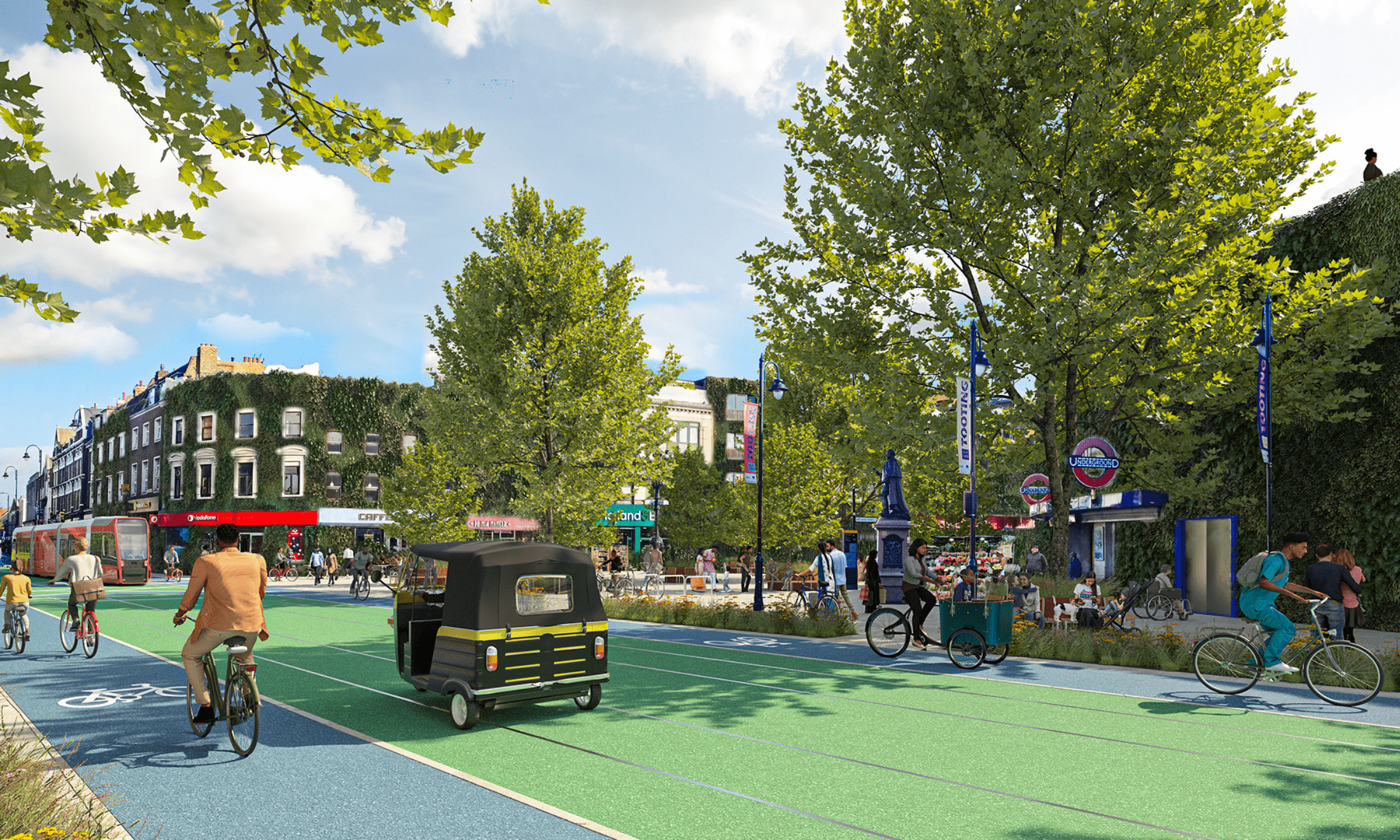

Whilst the terminology of environmental racism emerged from the organising of African American communities, the UK is equally committed to environmentally racist and classist policies. That is why Centric Lab, a citizen science lab with a commitment to health justice, has spent the past year producing ‘Right to Know’: a postcode tool that enables people to understand the environmental health trends in their area. But it’s more than just a tool for accessing information – Centric Lab wants to help create ‘healing futures’, using indigenous wisdom to build a world where our environments are in symbiosis with our bodies. They do this by building digital infrastructure, such as tools and organising spaces, that supports a strategy for health justice. Change happens through citizens, the more people that know about how health relates to the environment, the more people will be motivated to seek ways to improve poor environmental conditions.

Most of us do not have access to data that helps show how the places we live could be making us sick. However, plenty of community organisers were making the link between environmental pollutants and public health way before professional institutions were willing to acknowledge it. Take for example the fight for justice for Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah, which is pushing to have air pollution noted as a cause of death on her death certificate. Or the Newham community resisting the Silvertown Tunnel development, sewage watch along the Thames to keep our rivers accessible, and every local airport expansion campaign – each acutely aware of the increasing threats to their community’s health.

“Centric Lab has spent the past year producing ‘Right to Know’: a postcode tool that enables people to understand the environmental health trends in their area”

We have the Right to Know if there are environmental factors in our neighbourhoods that could be affecting our health. Those exposed to high levels of noise can understand why they may be more at risk of cardiovascular diseases, or that too much light at night prevents us from accessing deep nourishing sleep cycles – a risk factor for depression. There is now an abundance of data and information about specific environmental pollutants, such as light, heat, noise, particulates, water contamination, and their relationship to poor health outcomes. For this information to support health justice, it must be extracted from scientific journals and delivered by community-led initiatives such as town halls and organising meetings.

‘Right to Know’ supports community organisers to think beyond environmental racism as a problem of being close to the ‘frontline’ of environmental pollutants (sewage works, landfills, incinerators or roadways). A power analysis that respects oppression as an environmental force that influences health is also needed within public health discourse. What this means for marginalised communities is acknowledging the everyday trauma of living in a racist and classist world, and how this has weakened the bodily defences of working class people of colour so much that the impact of environmental stressors are amplified. This physiological dynamic between us and where we live is known as biological weathering, and it is an essential piece of the puzzle for any climate justice organising and action. It is for this reason that Right to Know incorporates a deprivation index within its postcode analysis.

This is the essence of public health practice: to address ill health that is both unfair and avoidable. Public health practice has its roots in the health of working class communities’ relationship to their environments. Back in 1848 this centred around public investment in clean water and sanitation systems. Health after all, is political – it requires the government to respect its responsibility to create conditions for good health. It’s no surprise therefore that in the past month we’ve seen the demise of Public Health England as an agency who held responsibilities to address “health inequalities”. This is the government washing its hands of the responsibility to address unfair and avoidable ill health within marginalised communities – paving the way for innumerable future injustices at the hands of government policy, local authorities and private companies.

Communities – especially diverse ones – have historically been the crucial element in achieving health justice and environmental rights. Their work always goes beyond the boundaries of their own communities – driving equity and justice for everyone –and this is the essence of collective organising for climate action. The work of Clean Air for Southall and Hayes, a predominantly Punjabi Sikh and Black community group seeking to end the leaking of carcinogenic chemicals from a redeveloped gasworks site, has motivated various other communities in London to take similar action so that they too now have the chance to avoid the same fate.

“This is the essence of public health practice: to address ill health that is both unfair and avoidable”

Beyond the tool, Right to Know will facilitate these cross-community relationships so that the momentum builds for resisting further injustices. In the absence of Public Health England, and any formal government resources to address inequity – it is up to us to collectively prevent illness and death in the most marginalised communities in the UK.

Right to Know is hosting a “Demo Day” on Wednesday 27 October which is open to anyone interested in using it for their community organising and climate justice work. Click here to find out more.

Guppi Bola is a health justice organiser and current chair of Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants.

For too long, both climate activism and climate coverage have overlooked the voices and experiences of communities of colour. Follow our new series, It’s Happening Now, for stories that look to change that.