Diyora Shadijanova

Hope is quashed: what it’s like being queer in Ghana right now

A queer Ghanaian writer shares their experience following the violent closure of an LGBT+ centre in Accra.

Joojo Sekyibea and DiyoraShadijanova

12 Apr 2021

Content warning: mentions of violence

It ended as theatrically as it began. On 24 February, a moral panic surrounding the opening of an LGBT+ centre in Accra, Ghana, ended with police officers dramatically storming the location without a warrant, breaking into the building, searching through every room (with cameras, of course), and locking the centre with a chain and padlock. For queer Ghanaians like me, this was only another day where our country reminded us that the promise of “Freedom and Justice”, our national motto, was not meant for every citizen.

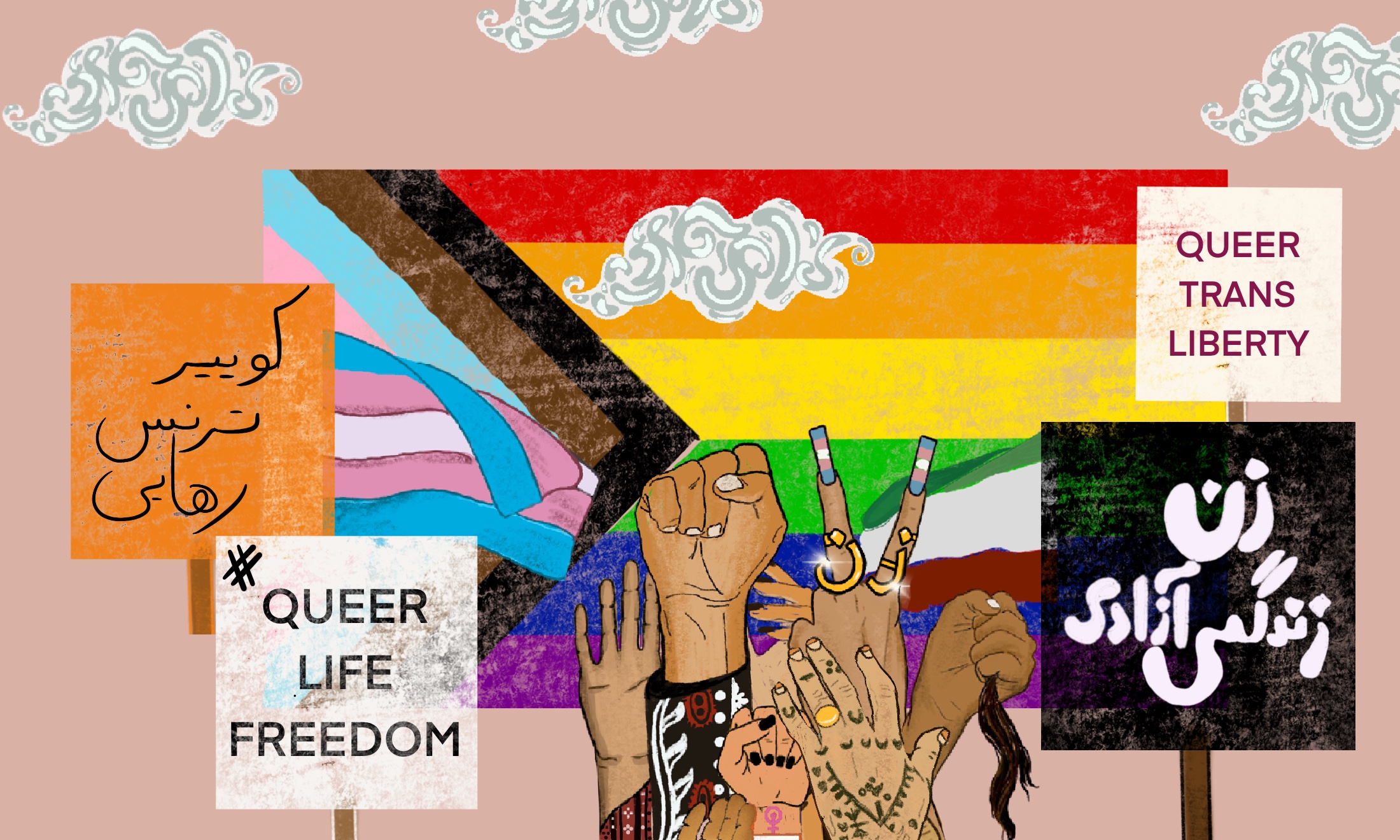

I remember where I was when I first heard about LGBT+ Rights Ghana’s new centre. A good friend of mine is a member of its executive leadership, and it was at her apartment late December that she revealed to our shared gayggle that they had rented our a building in the outskirts of Accra, and were planning on turning it into a multipurpose centre: a safe house, library, coffee shop, resource centre, and pop up health centre. All they needed was some help cleaning it up, and importantly, painting a huge mural of the queer flag in the lounge, a rare mark of welcome and ownership in a country that constantly othered us. Every streak of paint on that wall that December was a hopeful investment by a queer person or an ally in a better future for us all.

The grand opening in January was to quickly quash that hope. It was well advertised all over social media, and so it was a pleasant surprise that it went on without a hitch or interruption from state officials. However, public interest was piqued when people began to see images of public figures who attended the event. These included celebrities like Wanlov, a famous (or rather infamous) musician and provocateur, as well as diplomats like the vocal Australian high commissioner (who later got summoned to parliament to “explain his actions”).

When people finally placed them as attendants of the opening ceremony, their anger was immediately palpable. They did not know or care, where it was located. In fact, for the first two weeks of news reports, journalists consistently got the location wrong, suggesting that none of them had made the effort to visit the place.

“What struck people most was the audacity of queer Ghanaians like me to even dream of having a community space”

Instead, it seemed what struck people most was the audacity of queer Ghanaians like me to even dream of having a community space where we could congregate, and well, be queer. People were outraged by the sight of that very LBGTQI+flag mural that I had participated in painting and threatened on Twitter to flog us. Others speculated on the beds; perhaps they were for the orgies that, surely, all queer people must regularly partake in to maintain our membership in this club? I wish I was making this up.

Pressure began to mount from different civil society groups for our government to ‘do something’, despite the fact that we have the right to assembly. Religious groups declared the centre, and our very existence, an affront to the God of any faith (few things unite religious denominations in Ghana like we do), and the traditional leaders of the community threatened to burn the building down. Even ministers of state had to come out to signal their moral positions, declaring the criminality of our existence ‘non-negotiable’. No one was surprised when finally, about a month afterwards, the place was shut down. I daresay it was even a relief to some of my friends; at least the scrutiny would die down.

I do not blame them at all for feeling that way. The psychological toll of being constantly reminded that you do not belong, of having your life and livelihood threatened, of having to more consciously conform to social conventions of what it means to be a man or woman, those real burdens were heightened everywhere: in the media, on social media, in their homes, and on the streets. I have a friend who was assaulted by a security officer because he could not tell their gender.

“I have a friend who was assaulted by a security officer because he could not tell their gender”

Another video making rounds was of a bloodied man, lying prostrate, being poked and prodded with huge sticks, one with spikes, while he was being derided for being gay. The fear was palpable. For those grappling with reconciling their gender identities and sexualities with their upbringing and culture in an inhospitable society, many have been pushed back deeper into the closet. Many are now doubting their self-worth. Lest you think this was an isolated incident, just last week, 22 women at a party were arrested for organising what the state calls a gay wedding, despite the ladies insisting it was a birthday party. Does it matter what the purpose of the gathering was?

During this onslaught, all we could take solace in was each other, and many in our queer community stepped up in admirable ways. Many queer activists, especially queer women (yet again), quickly rallied to assert the presence and validity of queer life, to remind me and my friends that we mattered. Many, both within the country and in its diaspora, took to the press and social media to call out the very obvious injustices and defend the constitutional right to assembly. That we found among these allies notable journalists, and even a parliamentarian, restored a little of the hope that almost got snuffed out. More uplifting news, the organisation behind the closed centre is currently undertaking a quite successful fundraiser to procure new space.

For now, while there is a general sense that this was a setback on our march of progress, we cannot dwell for too long on this. Some parliamentarians are threatening to clarify, Section 104, the part of our legal code used to threaten us under laws of “unnatural carnal knowledge”, to explicitly classify homosexuality as criminal. We are doing, and need to continue to do a lot of strategising, organising, and building allies. We are also checking in on each other a lot more, and tending to our communities. Rights mean nothing if we are not healthy enough to enjoy them. Looking forward, the journey seems daunting. But we cannot afford to give up. Our wellbeing, and our very lives, depend on it.

*The writer’s name has been changed to protect their identity.