As a child I wasn’t given access to any information about the long-lived devastation of the transatlantic slave era, so I had trouble associating any of it with the breathing spaces of my own existence. The Civil Rights movement was a two-page incident in textbooks, which happened somewhere in the US decades ago. As far as I knew, Malcolm and Martin rocked up, saved the day, and everything turned out fine. So when the dots finally connected, I received the slave narrative as a rude awakening. “Wake up!”, the voices of my ancestors warned me, “This isn’t over yet!” After that initial jolt of fear comes the desperate need to understand more.

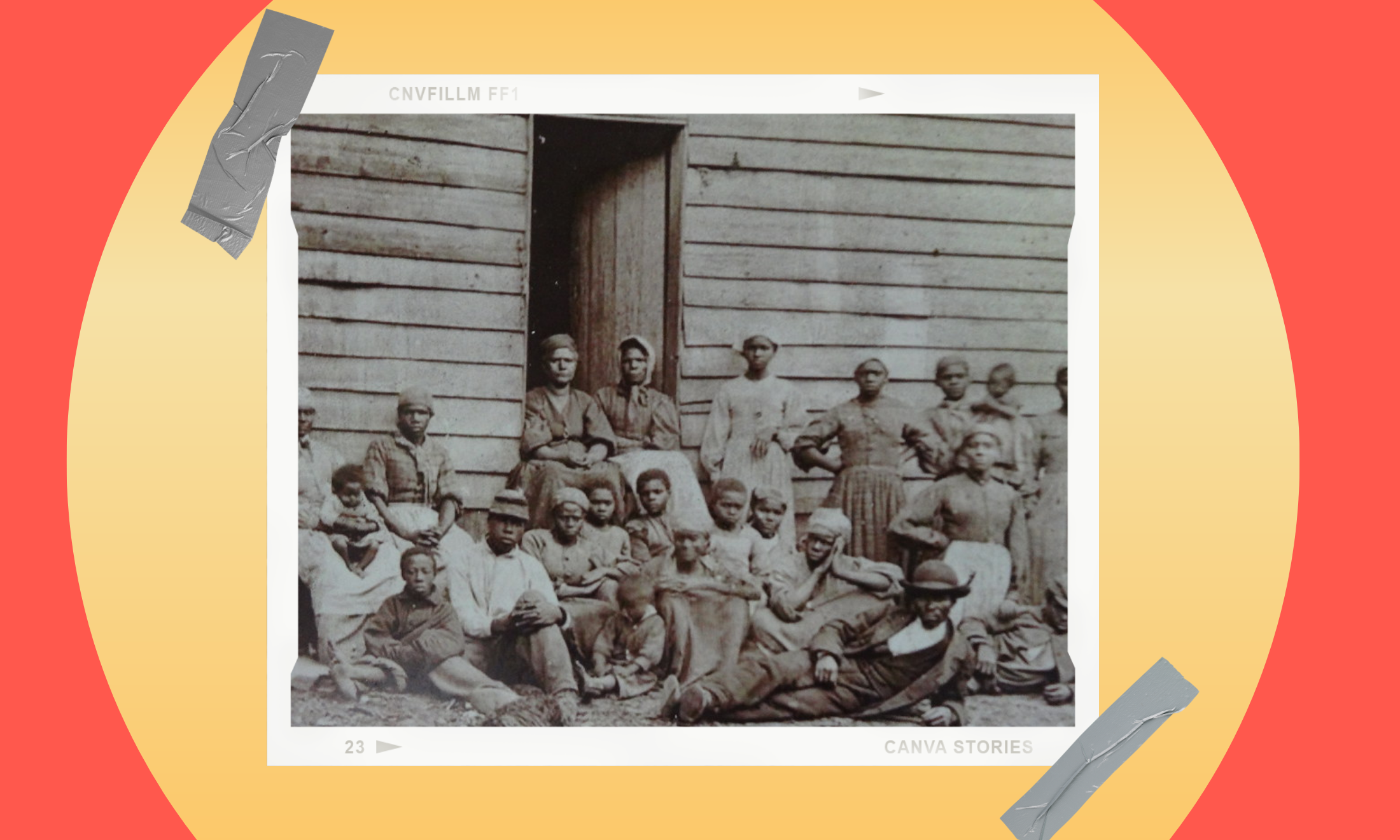

Twelve Years A Slave was the first film I had ever encountered that didn’t trivialise the true horrors of slavery. I saw it at a tiny cinema while living in Paris, and on more than one occasion during the screening, I remember hurriedly gathering my things to leave – unable to sit through the relentless brutality. I’m not a masochist; I firmly believe that these films testify to the enormous resilience of the people from whom I derive, which is important to me in the process of honouring them, honouring myself, and contemplating our collective need for justice – in the form of reparations. I recognise the survivors of that story as myself, and all the other black people that I knew. We had survived and we had kept living, but not without damage.

Once I began to learn about the long-lasting impact of slavery, I couldn’t continue to exist in the world as I was; denying the role that my skintone played in all of my experiences, and ignoring the fact that the vast majority of problems in the black community could be traced back to enslavement. On a spiritual level, African souls carry the distress of the ancestors and on a scientific level slavery has been written into our DNA. It is hard to deny that this is a legacy left untreated. I accepted that our complex history deserved analysis and understanding rather than just complaint and frustration.

There were 12,000 known British and British colonial slave voyages with 210 million carelessly-documented African lives stolen in the overall process

Detailed accounts, evidence and solid research are readily available, proving that the British were up to their necks in African blood from day. There were 12,000 known British and British colonial slave voyages with 210 million carelessly-documented African lives stolen in the overall process. Worse still, these figures are likely to keep rising as research continues. Another grim fact that sits largely unknown is that the British kept enslaved Africans on home soil as well. Merchants, government officials, and members of the military returned home from abroad with their “chattel” in tow. Since it was widely accepted by the British that Africans were not really human, our people could be bought and sold in the English newspapers.

What does it really mean when I read that African people were property? It means that enslaved men, women and children were traumatised throughout their entire lifespan. It means that black girls and women were routinely sexually assaulted and their genitals experimented on, black men were raped in front of their sons, and black children were starved, beaten, brutalised, and all forced to labour right up until their deaths. Even when the slave trade “ended” in 1807, and the fresh supply of African lives was legally cut off, it took a whole additional generation before the British put a stop to colonial slavery. Abolition in Britain in the year 1833 cost the government a dizzying £20 million in compensation. Even more of a headfuck, let this sink in: that money was not given to the enslaved Africans but to the 64,000 British people who had “owned” them.

The oppressors were given cheques for their financial losses and the Africans were given a big fat fuck you

I wish I could jump straight into repair. But before Africans can even begin that process, the damage must immediately cease to be inflicted. Because of this, I joined #StopTheMaangamizi: the official campaign for reparations. Maangamizi is a Swahili word which refers to the African Holocaust of chattel slavery, colonial slavery, neo-colonialism and imperialism which continues to destroy African lives globally to this very day. Stop The Maangamizi is a grassroots initiative for reparations whose aims are to conduct an independent inquiry into reparations and hold the British State to account, whilst taking responsibility for the rebuilding of our own authentic African selves. Or as the official Stop The Maangamizi campaign spokeswoman Esther Stanford describes: “Education is preparation for reparations.”

Reparations isn’t just about money, it’s bigger than that. The first argument that people have against reparatory justice for Africans is always along the lines of: “But where would the money come from? Out of whose pockets?” On the heels of that question they often ask: “Where would that money go? None of you are slaves and not all of you are descendants of slaves! How do we know who is owed and who isn’t?”

What these people fail to understand is that reparations is holistic repair, and it’s important to acknowledge that all black people – whether or not they are the direct descendants of slaves – suffer the legacy of slavery which is the catalyst for the invention of afrophobia and outright racism in today’s society. So in identifying who should benefit, the answer is: all of us.

The five pillars of holistic repair are as follows: restitution, compensation, rehabilitation, satisfaction and guarantee of non-repetition. Black people, given the money owed from the stolen lives and labour of our forefathers, would only return to our current position within a small number of years without a penny of it left. Not because we’re flashy and tun up for no good reason, but because a community that cannot understand the value of itself can never understand the value of money. Thus, a simple handout won’t do. An economic shift will only last if a political shift and a social shift takes place simultaneously.

True reparations will see the British held accountable for the continued genocide of Africans as a specific measure of closure

True reparations will see voluntary rematriation/repatriation back to Africa as a specific measure of restitution. True reparations will see counselling and psychological support made readily available to black people as a specific measure of rehabilitation. True reparations will see black people invited to give testimony to the specific ways in which the Maangamizi has damaged their lives and that of their families as a specific measure of satisfaction. This is but a taste.

The Reparations Committee campaigns by distributing flyers and leaflets, doing outreach on the streets of London, participating in protest marches about race, sending letters to local MPs and giving talks and presentations within the community; ensuring that we are well-versed in recognising the confusion tactics employed by the British State to stop us from reaching our goal. Every member is trained in responding to the typical comments of those who push back against the restoration of African consciousness. The annual Reparations March takes place Emancipation Day on 1 August starting at Windrush Square, ending at the Houses of Parliament where we present the petition to number 10 Downing Street and including a three-minute silence to acknowledge the scores of black lives lost.

Black communities are not the only people who would benefit from the release of reparatory justice. White people are trapped in whiteness too. Their superiority delusions, their cognitive dissonance, all that energy spent on denying what is plain, and discounting the experiences of black people is totally pathological. Our injuries are left to fester. Only with acknowledgement can we begin to recognise the enormity of the crime and allow the healing to begin. In her book Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race Reni Eddo-Lodge discusses the importance of affirming ourselves and our right to be here. She writes:

We need to change narratives. We need to change the frames. […] We need to let it be known that black is British, that brown is British and we are not going away

In the history of crimes against humanity, victims regularly receive reparatory justice and have their complaints legitimised. Yet the plight of black people continues to be ignored and our complaints gaslighted and we’re expected to just keep taking it. Since history clearly demonstrates that the British State doesn’t care about us or the change we need, reparations is our roaring retort. We’re gathering people power, we’re organising and we’re bringing about the change ourselves. Who needs the British State to care? Reparations is self-care en masse.