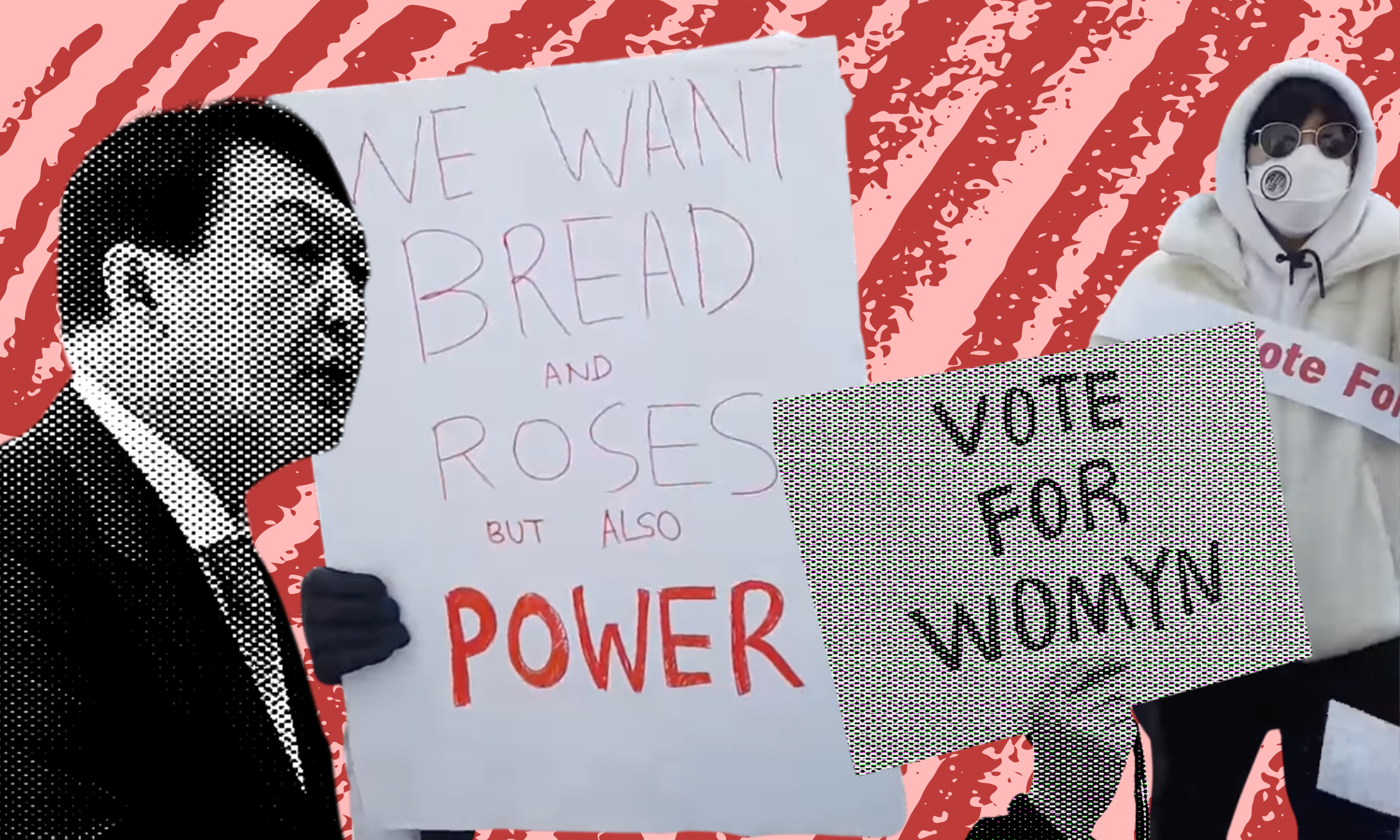

South Korea elected a president on a platform of misogyny. Feminists in the country are fighting back

‘Anti-feminism’ swept new South Korean president Yoon Suk-yeol to victory. But feminists are not giving up without a fight.

Hanna Pham

25 Mar 2022

Flickr/YouTube

“I threw up and cried.” This was 30 year-old Haein Shim’s reaction upon hearing the results of South Korea’s presidential election on 9 March. As senior director of foreign media of Haeil (translated as ‘Tsunami’), a Seoul-based feminist group, Haein felt that neither candidate was necessarily a strong or progressive choice. But in Haeil’s eyes, the worse of two evils, Yoon Sul-yeol of the People Power Party, prevailed.

“We have to choose the head of the state, but there is no candidate for women to choose from,” Haein tells gal-dem, speaking from the US, although she originally hails from Gwangju, in south-west South Korea. “No candidate sees women as they really are.”

Yoon Suk-yeol, South Korea’s incoming president, is a controversial figure. He ran on a platform promising to tackle class inequality and get tough on China, while aligning more with the USA. But central to his campaign were pledges to address the grievances of young Korean men who consider themselves anti-feminists, including abolishing the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family.

“In August 2021, at a Haeil protest, the operator of a misogyny site with 360,000 subscribers mobilised his followers to harass women present”

Suk-yeol’s opponent, Lee Jae-myung of the Democratic Party, didn’t instill much hope either; in recent years, the Democratic Party has seen a slew of sexual harassment scandals. But it was Suk-yeol’s active misogyny that won him the day, borne to victory on the backs of male voters in their twenties and thirties. Despite the new reality of an incoming president who doesn’t believe structural discrimination based on gender exists in South Korea, the country’s feminist movement is determined to fight back.

Their struggle does not come without risk, however, and on multiple fronts.

While the likes of economic discrimination and sexual harrassment dogs women in the country, rising anti-feminst sentiment means their physical safety and security is also constantly threatened. Yujin, a feminist who has protested before with Haeil, recalls how in 2019, she was followed by “one or two incel men” on her way to a protest. Women often are forced to wear masks, sunglasses and caps at protests to conceal their identity and evade surveillance.

Retaliation against feminist movements has only increased. In August 2021, at a Haeil protest that Yujin attended, the operator of a misogyny site with 360,000 subscribers mobilised his followers to harass women present. According to Yujin, women at the demo were filmed without permission, accosted with murder threats, and chased with water guns.

“There have been men who have been following women’s demonstrations and acting threateningly since then, this was the first time that they have made money by following them in groups and broadcasting them in real-time,” says Yujin.

Easy scapegoats

Women were an easy scapegoat for Suk-yeol to alight upon in his bid for power. According to Ju Hee, the founder of Haeil: “Korea is a country with a long history of male supremacy that favours boys and aborts a large number of girls,” which has naturally spurred a “brutal patriarchy.” But, misogyny perpetrated by young Korean men today seems to diverge from the “traditional” sexism that emphasised stereotypical gender roles.

In their 2019 book Men in 20s, journalists Gwan-yul Cheon and data scientist Han-wool Jeong argue that young men in South Korea have rejected “the male privilege and the duty that typically comes with the patriarchal form of sexism”, such as gender roles and masochism. Instead, sexism is expressed via ‘anti-feminism’, an ideology based upon the belief that feminism is misandry

This difference can be perhaps partially attributed to how social media networks shape South Korean society. South Korea’s social media penetration rate, the amount of the population that is on some form of social media, is 80% higher than the global average of 49%. Misogynistic greivances have festered online and led to the creation of vehemnt anti-feminist groups like the New Men’s Solidarity Movement which has nearly 400,000 subscribers. A 2018 report by Ma Kyung-hee, a gender policy researcher at the Korean Women’s Development Institute, surveyed 3,000 men and found that the older generations thought women needed to be protected, whereas young men see women as a “competitor[s] to overcome”, who have unfair advantages.

Contributing to this emerging perspective is the consensus among young South Korean men against mandatory military service. Men between 18 and 25 are required to serve 21 to 24 months in the military, a law that women are exempt from. In a 2018 poll from the Korean Women’s Development Institute, 72% of the 1000 participants, who were young men in their twenties, thought that the male-only draft was a form of gender-based discrimination. Not only do men feel like they’re losing two years of freedom, the time lost gives women leverage to pursue opportunities while men serve. In addition, policies intended to tackle the gender wage gap like incentivising the private sector to hire more women made young Korean men feel like they are discriminated against.

Another grievance that young Korean men cite against feminists is their high unemployment rate. Government data indicates that Korean men in their twenties have the highest unemployment rate compared to other age and gender groups. The nationwide unemployment rate is 3.8%; for young male Koreans it is 9.9%.

“Young men see women as a ‘competitor[s] to overcome’, who have unfair advantages”

Alongside the high unemployment rate, young Korean men also feel like they are negatively impacted by the housing market. “Employment instability has increased due to the increase in non-regular workers, and housing instability is aggravating as real estate prices skyrocketed,” says Ju Hee, founder of Haeil. Housing prices are high; the average price for an apartment in Seoul is $670,000, while median income is just under $2,000 per month.

But rage at these social inequalities has been misdirected. “The youth’s anxiety and anger were directed not at the vested interests and power that caused problems, but at the socially underprivileged, that is, women,” Ju Hee adds. These misogynistic attitudes prevail even though in Korea, women earn only 63% of what men earn – the highest gender pay gap of all OECD countries.

Women, and especially feminists, are what anti-feminists diagnose as the root cause of Korea’s ails. “Even asking for women’s right to freely decide their appearance outside of the traditional image of women in the patriarchal system is considered a reaction against men,” says Ju Hee. “The reality is that they call it male hatred, not feminism.”

Continuing the fight

Rather than being a point of defeat, Yoon’s win is mobilising feminists. “We have no choice but to be unrealistic to some extent,” says Jooyoung, a feminist activist who preferred not to give her age or location. Danwoo Yun, an arts journalist an arts journalist and feminist activist declares that she “didn’t feel the despair of Yoon Seok-yeol’s election for a long time,” as she was motivated by feminists who protested during his election and continue to after his victory. “I’ve regained my will to fight against anti-feminism. I’m ready to fight again,” she says, firmly.

The premier anti-feminist facet of Yoon’s agenda is his promise to abolish the Ministry of Gender, Equality, and Family which was created in 2001, to improve gendered disparities and family welfare. Yoon states that the ministry treats men like “potential sex criminals” and wants to introduce tougher restrictions for false claims of sexual assault. This will make it even more difficult for women to seek help, says Ju Hee, as “victims of sexual assault are already attacked and criticized,” evidenced by the 2018 Korean Women’s Development poll, which found that 55% of men do not support the #MeToo movement.

While Yujin has attended protests before, she is about to run her first one, to oppose the abolition of the Ministry of Gender, organising via social media. Alongside this, she’s collecting signatures for a petition to ensure its survival. Haeil has also joined the fight to preserve the ministry, organising with other grassroots feminist groups like Women United by Courage and People Against the Pledge to Eliminate the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family.

According to Haein Shim, even though fighting for the ministry is not the only thing on Haeil’s agenda, protecting the ministry’s existence is an important symbolic battle in the fight for women’s rights. In 2017, the Ministry rolled out a five-year plan to expand the number of women in governments and public schools. Fighting for its survival will ensure help to “make change in the system,” says Haein.

Despite Yoon’s election, Danwoo remains optimistic and sees the election as “a half victory for females”. Feminists are banding together to fight for the survival of the Ministry by sharing petitions, creating viral hashtags like #voteforwomen, and sending their concerns and demands to both the People Power Party and Yoon himself.

“A lot of males, particularly those in their twenties and thirties, believe that abolishing the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family will bring about the end of feminism in Korea,” says Haein. But she’s still holding onto hope.

“However, if this happens, it will usher in a new stronger era of feminism in Korea.”

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?