#StopKony: 10 years on, how did a controversial campaign shape online activism?

A viral video aimed at white Americans provided the blueprint for the digital 'awareness' era.

Sunnie Fraser

04 Mar 2022

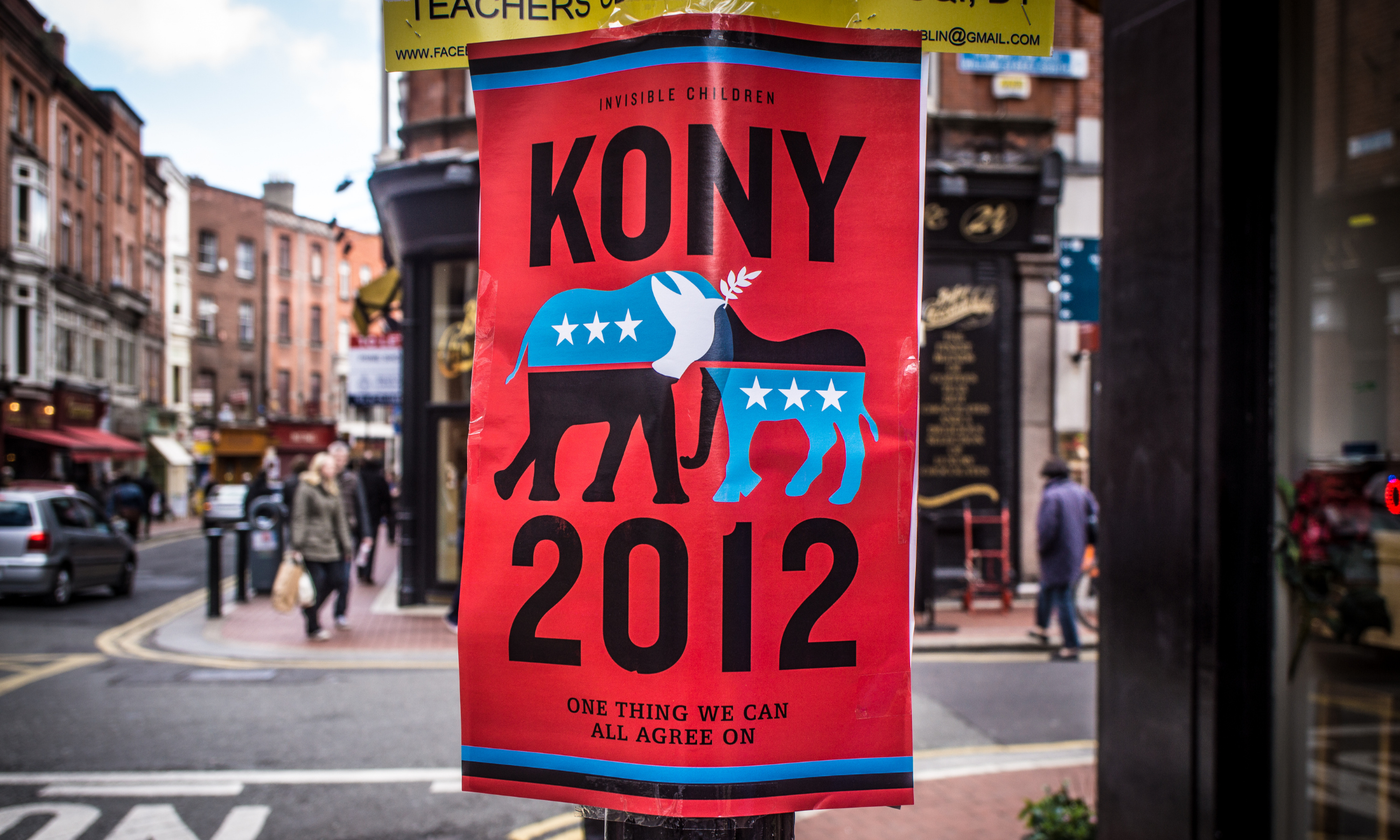

William Murphy/Flickr

It’s Thursday 15 March 2012, a sunny morning in San Diego, California. Suddenly, a flurry of calls light up the San Diego Police Department switchboard. A white man has been spotted, naked and distressed, running through the streets of the city.

It’s a harrowing scene. He’s pounding the pavement and ranting incoherently about “the Devil”. Some onlookers stop to film, as he intercepts ongoing traffic whilst shouting at passers-by. Eventually, the cops arrive. The man is detained for allegedly masturbating and being drunk in public, then hospitalised.

The young man was Jason Russell, co-founder of NGO Invisible Children. His meltdown was the climax of 10 days of virality. On 5 March of that year, Russell and his team had uploaded a 30-minute documentary titled ‘Stop Kony’ to YouTube. Its subject was Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony and the impact of his war crimes on Uganda – a country fraught by decades of socio-political turmoil. With Hollywood polish, Invisible Children pleaded for people to join their campaign to ‘Make Kony famous’ and spread the word of his use of child soldiers.

Invisible Children’s goal was to put enough public pressure on the US government to push them into deploying ‘advisers’ to Uganda who could apparently help Ugandan officials track Kony “in the vast jungle”. Invisible Children rolled out an ‘Action Kit’ and instructed viewers to help them target “20 culture makers and 12 policy makers”, including celebrities like Angelina Jolie, Lady Gaga and Oprah, who could use their platforms to make Kony a “household name”.

The video worked. Astronomically well. According to a poll released by the Pew Research Center on 15 March, the day Russell was sectioned, 58% of young American adults claim to have seen or heard about the video. And that was just in the US; worldwide, Kony was going viral. As of 13 March, the YouTube version of the video had racked up 76 million views, making it one of the then-most viewed clips of all time. And that wasn’t even counting Facebook shares, which were the engine of the campaign. As we teetered on the edge of a digital society of excess information, this statistic was emblematic of what was to come for the post-internet age.

Kiera Walsh first saw the hashtag #StopKony pop up on her Facebook feed when she was at sixth form college. She recalls online comedian Matt Lacey’s videos circulating at the time, mimicking “gap yah” teens who volunteer in developing countries. Although Walsh immediately recognised this same white missionary rhetoric being perpetuated throughout the Kony 2012 documentary, it was still too persuasive a campaign to ignore.

“To me, it seemed like a great cause, and I wanted to be involved in exposing this criminal,” Kiera says. She ended up sharing a 30-minute clip on Facebook and spoke about Kony in a Social Geography presentation.

“The whole campaign was extremely seductive. As humans, we need purpose to uphold our sanity and the feeling of being a crucial part in a puzzle fulfilled that need. I felt as if we were the solution,” she recalls.

The notion that civilians of the Global North were the saviours was integral to the success of Invisible Children’s campaign. In Teju Cole’s reflective piece for The Atlantic, he states that, “One song we hear too often is the one in which Africa serves as a backdrop for white fantasies of conquest and heroism.” Expanding on his ideas on social media, Cole coined the expression “White Saviour Industrial Complex”. The term took aim at the “white savio[u]r” who “supports brutal policies in the morning, founds charities in the afternoon, and receives awards in the evening”. The White Saviour Industrial Complex was ”not about justice,” wrote Cole. “It is about having a big emotional experience that validates privilege.”

“The whole campaign was extremely seductive. I felt as if we were the solution”

Kiera Walsh

The film suggests that raising awareness would directly influence the US government to take further action, following the 100 soldiers who had been sent to the region prior, allegedly, as a result of Invisible Children having initiated protests. But was calling for US involvement in Uganda really the answer? Less than four months earlier, the US had “officially” declared an end to their seven year war in Iraq; even by lowest estimates, it had claimed over 100,000 civilian lives by 2011 alone. US intervention hardly had proof of concept on its side as the answer.

There is something dystopian about this example of the mainstream white gaze on Africa and the way in which the West is force-fed images of deprived children in a crude and unjustifiably optimistic light. In the Kony 2012 film, the polished visuals distorted the situation in the region and the ease with which one could help. The irresponsibility of Invisible Children in suggesting that re-sharing and buying merchandise was the appropriate resolution was particularly unpalatable.

Fittingly, Black Mirror creator Charlie Brooker was one of the many critics of the movement, calling it a “slick, manipulative ad campaign”. The issue with the publicising of humanitarian missions is how difficult it is to differentiate them from explicit virtue signalling. This is an ongoing debate in popular culture, and today, public figures receive a considerable amount more backlash for engaging in exhibitionist altruism. Backlash to a 2019 image of BBC presenter Stacey Dooley posing with a young Ugandan child for Comic Relief was the beginning of the end of the tone-deaf benevolent celebrity volunteer. Last year, Comic Relief stated their intention to stop sending celebrities to Africa.

Reflecting on Stop Kony, Kiera Walsh adds that “the campaign created the illusion that Africa was a mass monolith and everyone there needed to be saved by the West, aka‘The White Man’s Burden’.” In the moment, she recalls the movement feeling somewhat patronising, and as time went on, she started to feel uneasy with the way the campaign had taken shape.

“The message of this type of mass consciousness coming to ‘save developing nations’ soon started to feel slightly off-key,” she says. Attending a majority white Catholic convent institution, which built a sister school in Uganda, contributed to Kiera’s ability to recognise the pattern of ‘benevolent’ Western charity in the messaging of this campaign and others she had observed previously.

As American academic Michael Parenti states, “[poor] countries are not underdeveloped, they are overexploited.” Despite Parenti being able to explain this concept in five words, Jason Russell avoided addressing the complexities of the situation in Uganda in his 30-minute film. Complicated truths didn’t go viral in 2012. The campaign forewent potential, sustainable solutions to the issue and flattened complex regional politics in favour of American intervention.

Stripping Africans of their autonomy is just as disturbing as stripping them of their literal freedoms and resources. Violence is learned and Europe’s colonial history with Africa provided a thorough lesson in violent behaviour.

To Russell, Kony was the antithesis of good. Allison Griffin, Head of U.K. Influencing at Save the Children, reiterates this, telling gal-dem, “Kony perpetuated this idea of the victim/helpless mode, which means [Westerners] are the helper, tapping into the white saviourism that still happens in the sector now.

“That works in a 30-second to 30-minute space to help offload your guilt and give some cash, but obviously the organisations who are really trying to turn the world upside down to make it fair for people who have had an unjust life for centuries need long-term, systemic change.”

Invisible Children used Jacob Acaye, a former child soldier under Kony, as their protagonist, a move that Griffin says is incredibly effective in campaigning. “For us, what people need to hear about are the powerful children who have overcome adversity and proven resilience,” Griffin says. “This leads to much better long-term engagement.” The problem was, Acaye was positioned merely as a vehicle and victim, rather than a person with agency, allowing Russell and his Invisible Children team to cast themselves, and the intended audience of Americans, as saviours.

“The campaign forewent potential, sustainable solutions to the issue and flattened complex regional politics in favour of American intervention”

And it wasn’t that Kony was a good guy – but lawyer, scholar and activist Kiran Grewal asserts that “[Kony] fits the classic image of the bad guy, confirming all of our colonial and racist stereotypes about violent, barbaric non-white men.”

Since 2012, movements ranging from #JusticeForGeorgeFloyd to Don’t Fuck with Cats have been relentlessly harnessing the internet to further their missions. Many have valid and important aims in their quest for virality. But the reaction of internet users can’t be controlled and emerging patterns frequently see responses to viral campaigns consist of mass hysteria, panicked social media sharing and then, the issue fading from public view. So did Kony 2012 teach us anything about ‘look first, then leap’? It doesn’t seem like it. But it did provide a blueprint for the complications of social justice movements successfully managing to tap into ‘armchair humanitarianism’.

“Slacktivism is something that we think of as faintly harmless,” says Rianna Walcott, an activist and PhD candidate researching Black identity formation in digital spaces at King’s College London. “I think that [there’s] a real con to it. Once the moment of viral outrage is gone, we forget the people who have been doing this work consistently.”

But it isn’t all bad.

Walcott adds that, “Certain groups can benefit from things like mutual aid, and donations. When it comes to white guilt and allyship, there was that moment [in summer 2020] where lots of groups were able to receive a lot of funding. If you’re able to harness this moment of white attention and use it, a lot of people are able to do good work with that money afterwards.”

Kony 2012 and the knock-on effect it had on modern activism developed our desire to spread information and raise awareness, expanding on the narrative that knowledge is power.

“Some of those tactics used, like the virality across social platforms, are still working today,” Griffin tells me. “[Kony 2012] was a great example of ‘crisitunity’, which is when you harness crisis and opportunity.” Suitably described by marketing institution Campaign Magazine as “a watershed in social action,” the movement evolved the awareness via social media rhetoric we are now so accustomed to.

The problem with the need for instantaneous and consistent information is that complex issues are condensed into short snappy Instagram infographics by anyone who has access to Canva and a spare five minutes. What this fails to acknowledge is the depth and intricacy of certain issues, and without depth one might truly believe that they are making real difference with the mere click of a button.

A Pew Research Center report found that 79% of Americans believe that “social media makes people think they are making a difference when they aren’t.” Kony was never ‘stopped’ by Invisible Children’s efforts. Despite an expansion in US involvement, he evaded capture, his forces already dwindling. As of 2017, combined US and Ugandan forces ended their mission to capture him, saying he was “no longer a threat”.

Since 2012, digital activism has become evermore prevalent and easy to engage in. The content has become more succinct and digestible, making it easier to penetrate more demographics of society. Yet true commitment to change stems from the ability to take a step back and recognise there is always more to learn. Whilst the power of galvanising millions of people via the internet cannot be underestimated, society must differentiate the delight of self-gratification from genuine philanthropic desire.