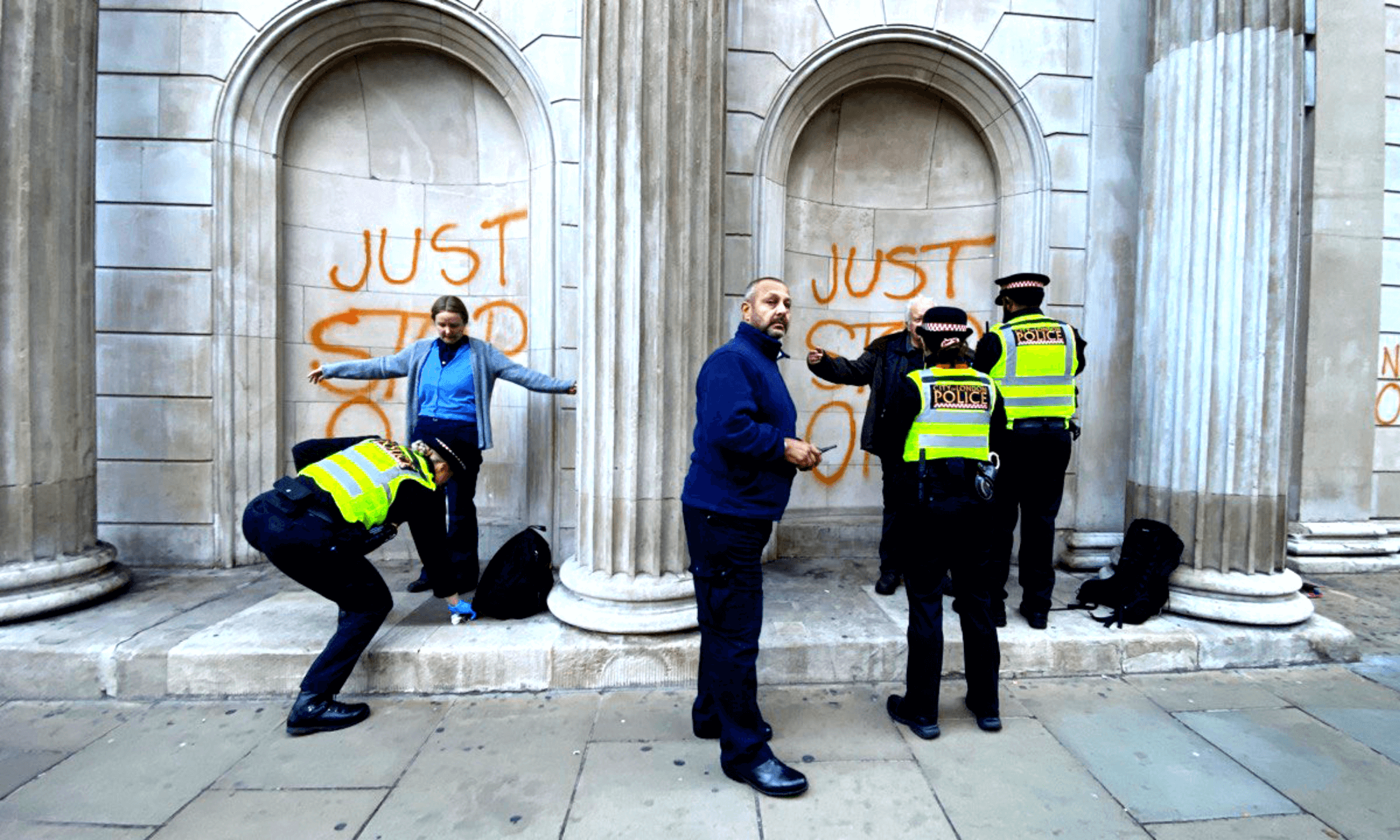

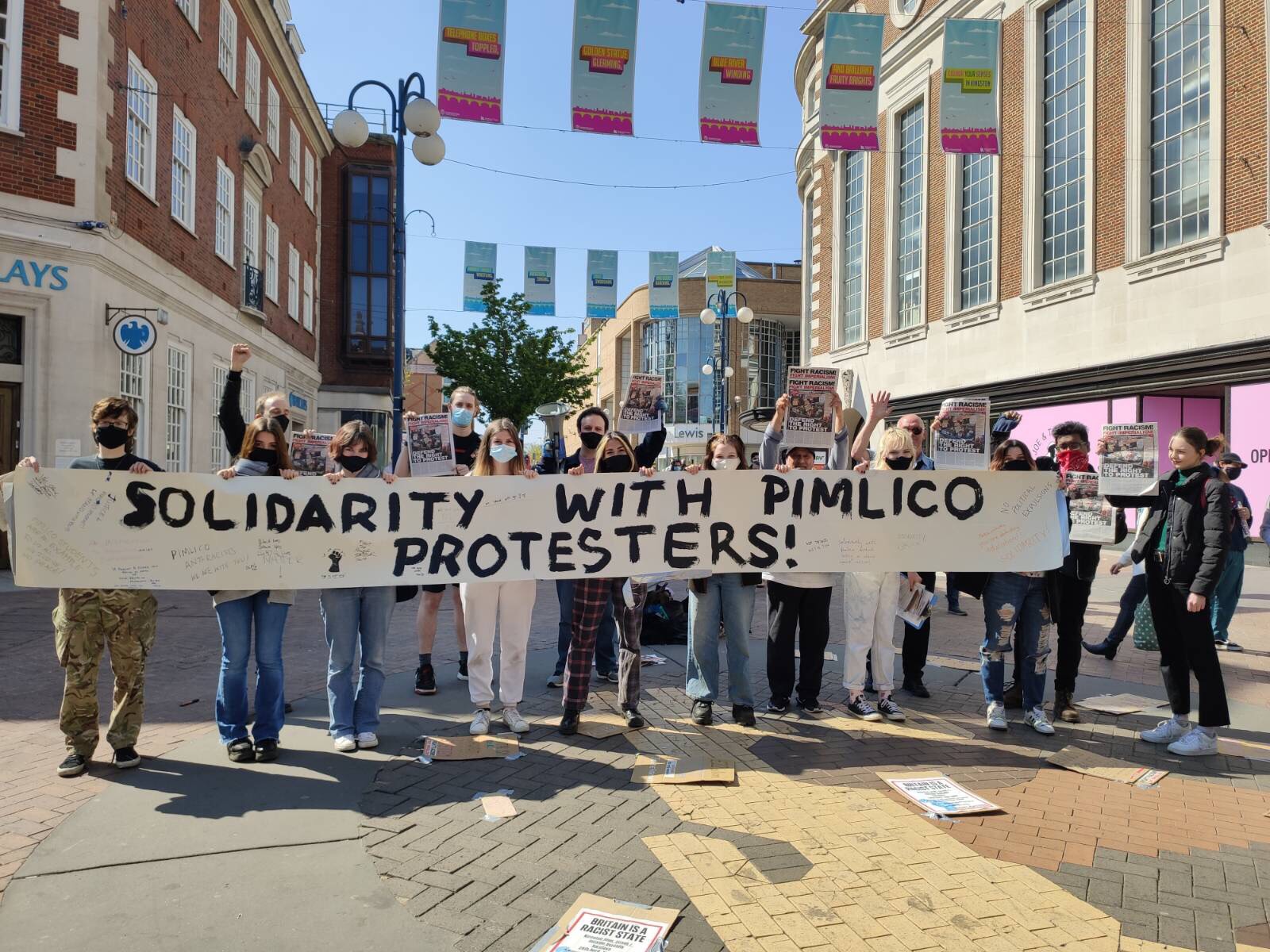

Photography via West London RCG @westlondonrcg

Students at Pimlico Academy are rising up because they know protests work

An organiser of the Pimlico Academy protests explains why even threats of school exclusions won’t stop young people from fighting for their rights.

Amna Mukhtar

19 May 2021

“We want change! We want change!”, was the battle cry of the students of Pimlico Academy on 31 March. All around us colourful signs of ‘97%’ and ‘BLM’ contrasted against the grey of the school. Placards were raised high as students chanted and sang, laughing with their arms wrapped around each other’s shoulders. At this moment, I thought of the headteacher sitting in his office and having to face hundreds of students holding him accountable for everything the school had put them through in the past academic year. Inspired by the direct results of other mass protests, we decided that our time to rise was now. Less than two months later, our headteacher resigned. But did we win?

Building tensions

Our protest was a reaction to building tensions that had reached a soprano screech. Six months earlier, fellow students started a petition against a uniform policy which introduced an expensive set of clothing for sixth form students – just two weeks before the academic year started. Understandably, many parents couldn’t afford the outgoing in the middle of a pandemic. But despite over a thousand signatures, the students at Pimlico were ignored.

Then at the height of the BLM movement, the school decided to fly the Union Jack outside the school and conduct several assemblies on ‘British values’. Our student body is incredibly diverse: the majority of pupils live in areas that are among the most socially deprived in Britain, and the proportion of those who are known to be eligible for free school meals is twice the national average. My friends and I found it strange that the shocking murder of George Floyd and the subsequent anger we felt about our own experiences of racism were completely dismissed, while these assemblies were repetitive, monotone and just like every other, compulsory to attend. When we voiced our concerns to a member of staff, we were told that they were “important”. So in protest and out of the frustration of feeling ignored, the students of Pimlico burned the flag and made front-page news.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t stop there. In September, hairstyles which “could block the view of other students” were also banned. Students struggled to understand why their natural hair, in particular afros, was considered a form of disrespect. “Colourful” hijabs also came under attack in the same policy. But the final straw for me was what I perceived as a weakness in safeguarding policies at the school. After speaking to multiple teachers and the headteacher about the issue, I left meetings hugging my new blazer against my chest and feeling very, very small.

Deciding to organise

“Reem, we should totally do this”, I told my best friend back in February, as I showed her a video of the protest at Highgate School, where there have been allegations of endemic rape culture. I stumbled across it online and was entranced by the sea of red jumpers and shouts for change. These students, with their fists raised high, sure as hell didn’t look like they felt small. Passion is contagious after all, and with the viral website Everybody’s Invited, exposing schools all across England for their shocking responses to sexual violence, we realised that we had power. When news of our plans spread across social media and started gaining more traction, it felt more and more like we could finally change things at Pimlico. Reem agreed and we spent a whole lunch time telling students to wear red for our protest, which took place on the last day of term.

On the day of the protest, I was completely shocked by just how many people attended. A whole playground was filled with hundreds of kids brimming with an earnest desire to change things. Outside the school gates, parents also offered their support. For hours, these kids chanted for change while one group of Sixth Form students (myself included) cleaned up after them and made sure they were all hydrated, and another group had a meeting with the senior leadership team.

It lasted until lunchtime, when the leadership team sent out an email to parents saying the school would be shut early “due to ongoing events at the academy”. All students who attended the protest missed their lessons but I made sure to walk around to each year group and spend time educating them on why we were doing this. Our main concerns were around what we as protesters felt were racist and discriminatory school policies and the fact that gendered uniform was still part of the school’s policy when non-binary and gender non-conforming students exist and are more visible than ever.

The majority of teachers were on our side, with one member of staff vowing to donate all his earnings from the week to a Black Lives Matter charity. One teacher who resigned and is set to leave this year told The Guardian that staff were feeling “demoralised” and had fundamental disagreements with some of the choices made by the academy trust’s leadership. She said that she could no longer work at a school that didn’t reflect her values. Roughly two weeks ago, The Guardian reported that the entire Geography department handed in their notices to show solidarity with a colleague who had been claimed to be dismissed earlier in the year.

Despite all this, the senior leadership team were more concerned with cutting the protest short and getting students back into classes. When I said that these kids were fighting to be properly educated about their own identities in a safe and accepting environment, a member of staff called me “inflammatory”. This, in itself, tells you all you need to know about the people responsible for our education.

The Future Academies’ leadership team’s response to the protests was awful, but unfortunately not surprising. Lord Nash, a Conservative peer and Founder of Future Academies, wrote a letter to the parents just before school reopened after lockdown, describing our legal right to protest as an act of “disobedience”. Our former headteacher, Daniel Smith, claimed “to reflect” and make changes but many of our demands are yet to be implemented.

The outcome and public reaction

As a school, we were successful: many of the damaging policies such as the Afro ban and headscarf rules were reversed and we even angered several white nationalists (which often means you’re striking the right chord!). But, like the #MeToo and BLM movements, it’s important not to disparage the means by which these changes happened.

The protest at Pimlico Academy was a clear dispute of the ruling that had been made on the very same day, 20 minutes away in Westminster, that claimed institutional racism did not exist. It attracted the likes of figures ranging from Nigel Farage (who produced a hyperbolic video highlighting the protests and talking about “Marxist teachers at Pimlico Academy”) to Jeremy Corbyn, who offered his support in a public letter to the school. Convicted terrorist and Britain First leader Paul Golding also weighed in by driving up to the school and attempting to interview passers-by. Though this was frankly scary and overwhelming for all of us organising, we tried to remember that the protest brought a community of students, parents, teachers and strangers together. We made a deep impression on the public consciousness on issues around discrimination and sexual violence in schools.

Yet still, all of the hard work of organising and making our voice heard went ignored as most media outlets opted to focus on the flag outside of the school, rather than the policies which made us protest in the first place. The successful reversal of policies was framed as the result of students being “exploited” by Marxists (as the Daily Mail so eloquently put it). The policies themselves were being presented as one school’s malfunction, rather than a nationwide issue threatening the safety and identity of students. Unfortunately, this is an age-old tactic of downplaying radical protests to preserve our blind faith in the course of history and those in power.

Protests work, but what happens now?

Against the backdrop of the pandemic, Derek Chauvin’s conviction and the Sarah Everard case, conversations among students have never been more determined. Though there is always a camp of naysayers and enablers in every movement, the majority of people are finding fire in their experiences. I couldn’t be prouder to know these people, to spend time with them and listen to their opinions. Teachers and parents are also angry, weighing options on what to do next.

So what happens now? The leadership team have warned that any further act of protest would “go against school values”, resulting in punishment. But to that I say – this is how change is made: by refusing point-blank to be obedient or well behaved. It’s snatched from the oppressive forces that rule us by protests, demonstrations and civil disobedience, not signed over by them.

The protest at Pimlico had lots of consequences. Our headteacher resigned. Politicians listened to students. Other schools protested and asked for change. The unpleasant fact is that transition occurs in disruptive forms. Accountability may have occurred in the Future Academies boardroom, but it started in the playground, in the streets and in the minds of young people who had grown tired of being angry.

Highgate. Batley. Pimlico. The truth is, schools should have always been a place of safety and inclusivity for young people. And now that we’ve realised how powerful we can really be, we’ll make it one – no matter how many protests it takes to get there.

gal-dem reached out to Pimlico Academy for comment but did not receive a response