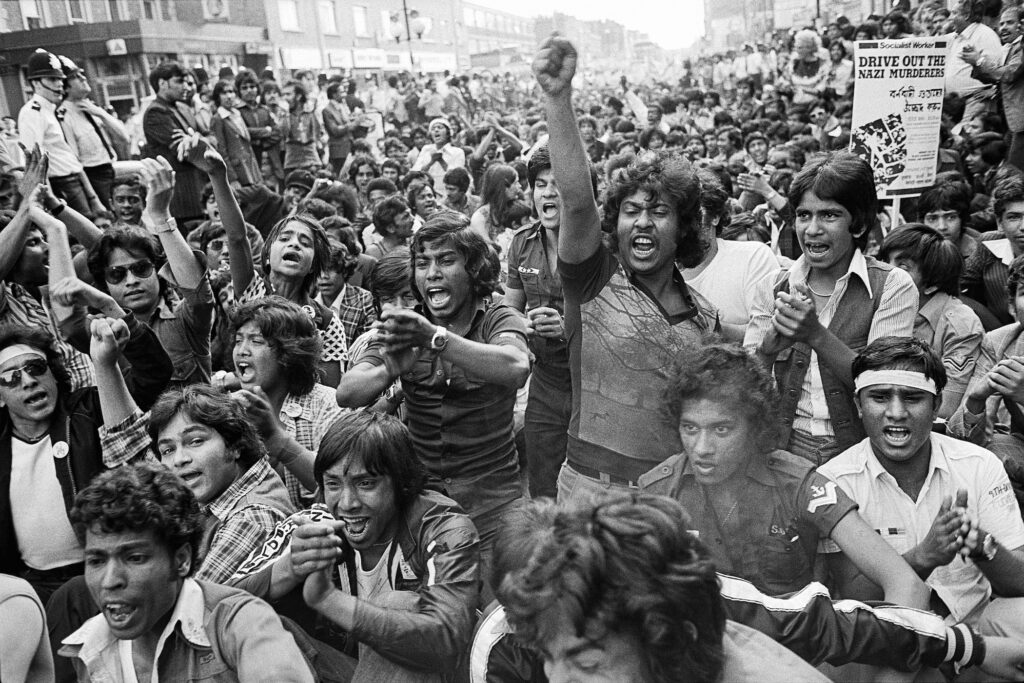

Courtesy of Four Corners/Paul Trevor

The summer of rebellion: remembering Brick Lane’s Bengalis and their fight against fascism

The murder of a Bengali youth in Brick Lane in 1978 sparked a summer of anti-racism protests in east London. A historical project by gallery Four Corners is now commemorating the long-lasting power of the movement.

Sophia Sheera

12 Sep 2022

Content warning: This article contains mentions of racism and discriminatory language.

On 4 May 1978, Altab Ali was walking home along the streets of Whitechapel, east London. Like much of the East End’s Bengali community, Ali lived in the deprived borough of Tower Hamlets.

It was local election day, and Ali had shopped for his evening meal before planning to stop by a voting station. However, Ali never submitted his ballot. Holding a shopping bag in one hand and a tiffin tin in the other, he was brutally murdered in broad daylight by three racist youths. At their trial some weeks later, the teenagers convicted of Ali’s murder told the court that they killed him for being a “Paki”.

The next day, the results of the local elections were declared. The National Front, a party notorious for its own particular brand of fascism, had won 10% of votes in four wards within Tower Hamlets. The popularity of the National Front confirmed that extremism was making a return to mainstream British politics.

Ali was not the first victim of racial murder, yet his death was the last straw for the Bengali community. Grief erupted into the streets. Ten days after Ali’s death, 7,000 protestors marched behind his hearse as it drove from Whitechapel to Hyde Park and onto Downing Street. It was among the largest demonstrations led by Asians in British history.

“A lot of the young people used to know [Ali], because he was a local person,” says Sunahwar Ali, who lived in Whitechapel at the time. “Everybody [was saying]: ‘we’ve had enough, now we need to do something about it’.”

Ali’s murder galvanised what is now known as the Bengali Resistance Movement, a series of protests that lasted throughout summer until September 1978. For many looking back today, the movement constituted a significant turning point for the community. “It was a very emotional event. Emotional in the sense that the event was not organised by the people, who were not professional in the political field. It was a spontaneous community response to a happening,” Rajonuddin Jalal, a founding member of leading activist group ‘Bangladesh Youth Movement’, recalled in the Bishopsgate Institute’s oral history.

“Throughout that summer of 1978, we were campaigning every day,” says Jalal. The protests, he tells gal-dem, “gave [a] voice to the younger generation of Bengali youth, who unlike their predecessors decided that [the] UK was their home and wanted to live here with equality, dignity and respect.”

I met Jalal and his community at the opening night of ‘Brick Lane 1978: The Turning Point’ at Four Corners. Dedicated to excavating forgotten social histories from east London, Four Corners gallery is currently collaborating with a British-Bengali charity, the Swadhinata Trust, to explore the political significance of the 1978 protests. As part of the project, Four Corners is exhibiting a collection of black-and-white stills of Brick Lane taken by local photographer Paul Trevor. These photographs capture the radical defiance of the 1978 protests.

At the exhibition’s opening, I watched as older Bengalis found themselves in the crowds of protestors in Trevor’s photographs. They stood proudly beside their displays of youthful courage while awed grandchildren took pictures, many surprised to hear of their grandparents’ past lives as revolutionaries.

The gallery stands at the heart of Banglatown, right where the protests happened. Within this space, the Bengali Resistance Movement is finally being lauded as a significant moment in recent British history, marking a critical juncture in the formation of British-Asian identity.

A youth-led resistance

Everyday racism was an entrenched part of life for the South Asians who migrated to Britain as early as the 1940s. As of 1961, there were an estimated 6,000 Bengalis in the UK; by 1981, the population had increased to 65,000, with 35,000 in east London alone. As the number of migrants grew, so did racist ideologies among white communities.

The first generation of Bengali migrants living in Britain reassured themselves that their suffering was temporary. “We are here to earn some money and go back to our country,” Sunahwar remembers being told. “People didn’t know how to report to the police, and the police were even more racist than some of the racist people within the area,” he says. “They had no intention to help our small community.”

Tensions between east London’s immigrant communities and those sympathetic to far-right ideologues like Enoch Powell had been brewing for years before Ali was murdered. According to Sunahwar, clashes between fascists and Bengalis “got much, much worse after ‘74. Nobody went to Brick Lane anymore because the National Front beat everybody up,” he says. Meanwhile, wider British society had little sympathy for the plight of the Bengalis. Four Corners picked out a quotation from The Observer in early 1978 that illustrates the indifference of those in power: “There is an easy rule of thumb when you walk through this part of the East End – the flats where Bengalis live are the ones with wire mesh over their windows.”

“People didn’t know how to report to the police, and the police were even more racist than some of the racist people within the area”

Sunahwar Ali

In response to increasing violence, young Bengalis started finding ways of defending their community. In 1976, Jalal and friends founded the Bangladesh Youth Movement (BYM) at the Whitechapel Centre where they attended English classes. They set up a youth club where young Bengalis could talk about “social issues and community affairs”. “If you go back to 1976, then you would find that the existence of the [Bengali] community was not really acknowledged in the wider arena and so having a youth movement as an organisation itself was an important achievement,” says Jalal.

Meanwhile, Sunahwar was involved in the formation of the Bengali Youth Front (BYF), a response to the Greater London Council’s “ghetto housing programme” – their controversial plans to racially segregate housing provisions. Sunahwar describes how Bengalis and white folks alike “in one voice opposed the ghetto”, after which “we decided to keep fighting”.

These two youth organisations would become the leading forces of the Bengali Resistance Movement.

In another corner of Tower Hamlets, young men formed vigilante groups and took turns guarding the most vulnerable estates. Another leading activist, Shova Motin, tells me that after their shifts, many young men would turn up at her place for a hot meal. “Two o’clock, three o’clock in the morning, they would knock on my door and I would open,” she tells me. Behind closed doors, Shova also designed and printed leaflets which the men “plastered on every building in Bethnal Green”. In bold red letters, the posters read: “Stand Against Racism”.

“Something needed to be done and we did it”

Sunahwar Ali

After Altab Ali’s murder, the community worked with local anti-racist groups like the Anti-Nazi League to keep up the momentum of the movement. During this time, the BYF and BYM became instrumental in organising the community’s efforts. On 18 June 1978, 4,000 people marched through the East End to protest racist violence, led by a coalition of Bengali youth groups. 17 July saw 8,000 restaurant and factory workers around Brick Lane strike in the name of anti-racism, joined by hundreds of children who walked out of local schools to join the effort. On 10 September, the ‘Carnival Against Racism’ – a nod to the wider Rock Against Racism movement – was staged in St. Mary’s Gardens, later named Altab Ali Park.

“Something needed to be done and we did it,” Sunahwar says.

The Bengali community also took a direct stand against the National Front. For months, the party had been handing out its fascist newspaper every Sunday at the junction between Brick Lane and Bethnal Green. Despite complaints from locals, police said the organisation was within its rights to sell the paper.

In response, the BYF occupied the junction. Sunahwar and other members spent their Saturday nights on a corner notorious for racial violence, armed only with their sleeping bags. “We were occupying the place and passing our time, maybe playing cards and singing and so on, while some of us were sleeping.” The Bengali community garnered so much support in the media that the National Front was forced to move its headquarters from Great Eastern Street to south London by the end of 1978.

Over the following years, the National Front dissolved entirely into factionalism. By the time the splinter-group British National Party (BNP) attracted attention in the 1980s, the Bengali community had formalised their political allegiances. In 1980, 16 youth groups including the BYM and BYF formed the Federation of Bangladeshi Youth Organisations in order to represent Bengali interests in Tower Hamlets and nationally. Over the coming years, they would work together to advocate for better housing, educational reform and access to healthcare across the UK.

Bengalis also began to join the sphere of local politics. Sunahwar was told in 1979 that there were “no vacancies” at the Labour Party, but by 1980 Jalal was elected to local council whereupon he quickly began “recruiting Bengalis actively”. Sunahwar, too, was elected a Labour councillor for Tower Hamlets in 1994.

“The people who fought that battle are the real heroes of our community”

Doros Ullah

I asked Doros Ullah, former civic mayor of Tower Hamlets, whether the protests of 1978 truly constituted a turning point for east London’s Bengalis. “The people who fought that battle are the real heroes of our community,” Doros says. “They contributed enormously not only to the Bengali community, but to British society as a whole.” Doros was only 15 years old when he took a coach from Birmingham to London in order to attend Altab Ali’s funeral. He credits the events of 1978 as the starting point of his political career.

“We never thought we’d have a councillor, never mind Asian people becoming MPs,” Sunahwar adds. “It never came to my mind, or anybody’s mind, I think, that there would be so much change or that we would become part of history.”

Read more about Brick Lane 1978: The Turning Point at Four Corners here.

Our groundbreaking journalism relies on the crucial support of a community of gal-dem members. We would not be able to continue to hold truth to power in this industry without them, and you can support us from £5 per month – less than a weekly coffee.

Our members get exclusive access to events, discounts from independent brands, newsletters from our editors, quarterly gifts, print magazines, and so much more!