When a person of colour becomes the first to do something, their names are entered on to a register. If you’re black, it’s the “first black register”. All the cool black people are there. President Obama’s name is on there. Haile Selassie, the Ethiopian Emperor is on there for being the first black guy on the cover of TIME Magazine. Mae C. Jemison as the first black-female astronaut, and so on. They are held up not just as individuals, but as representatives of other people within their race. “The first person to” narratives are necessary, but patronising at the same time. These achievements are often used as evidence of an exception to a wider, more negative stereotype of a certain group. However, they are also required in recording the greatness of people who belong to groups often artificially held back due to prejudice.

People of colour do this too. I mean, they make representatives out of their people who have platforms, including storytellers. Especially storytellers.

K’naan of ‘Wave Your Flag’ pop song fame, recently launched his HBO series Mogadishu, Minnesota which centres on the character Sameer, a second-generation Somali-American, and his navigation of two cultures. The launch event was protested by a group of Somali-Americans who had concerns that the series would portray Somali characters in a typecast: as terrorists, extremist sympathisers and segregated from American culture and society. K’naan ended up leaving the event early, and things turned ugly when police stepped in, pepper spraying some of the young protestors in attendance.

This is a constant battle for storytellers of colour. They balance the desire to not feed into mainstream stereotypes of themselves and their communities, whilst trying to write heartfelt stories and narratives that are personal to them and their imaginations, not just their kin.

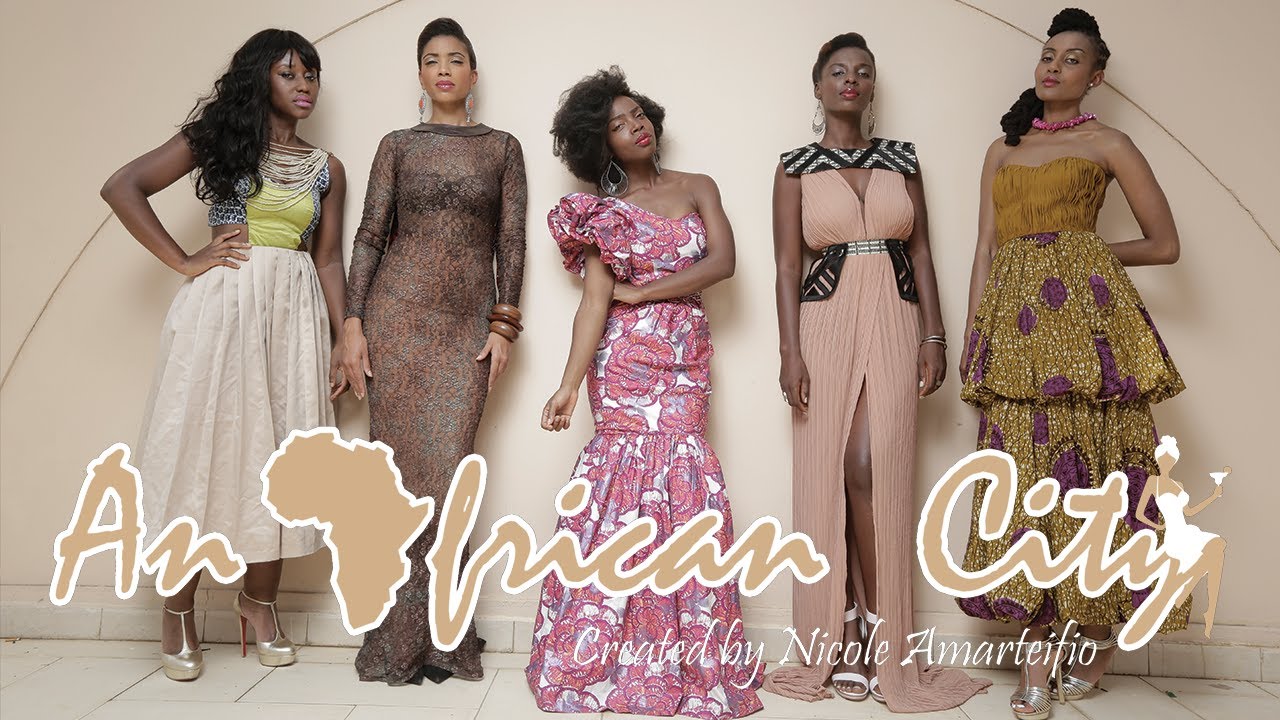

Maame Adjei mentioned similar challenges when discussing the successful web series, An African City, in which Adjei plays Zainab, one of the main characters. Speaking at London’s Africa Utopia festival earlier this month, Adjei detailed how the first season of the show was consistently critiqued by viewers for being unrelatable to the average woman in Ghana, where the show is set and filmed.

Adjei explained that show, created by a Ghanaian-American Nicole Amarteifio, documents the lives of five diasporan returnees to Ghana, who have been raised in the US and the UK. Based on Amarteifio’s experiences, who is a returnee to Ghana herself, the show is specific to that particular experience. Adjei went on to say that as season one progressed, the show explored themes that were common experiences of Ghanaian women and Ghanaians in general, as well as wider discussion about the African continent.

People of colour are hyper-sensitive to their portrayals in the media for good reason. Both Mogadishu, Minnesota and An African City, share the blessing and burden of being the first of their kind to reach Western audiences. However, it is so important that writers be allowed to write freely without feeling the pressure to produce pieces which are propagandist and a forced attempt at countering negative societal stereotypes. Not every writer of colour is writing to their community when they use them as the backdrop, nor should they feel the need to be overly wary of the white gaze when they are creating.

Both series also grapple with topics which are controversial for their “host communities”. Maame Adjei remarked that An African City often challenges the expectations of women in Ghanaian society, particularly with its overt protrayal of the characters’ sexual liberation. K’naan’s series is to address the issue of extremism and radicalisation. No group is perfect, and whatever subjects storytellers are exploring, communities should be sympathetic to their desire to write about real life. Covering up the negative about a group or community will not only be glaringly obvious, but may also attract criticism for not being brave enough to tell the truth.

Expecting creators to represent us as people of colour is wholly unfair. As viewers, it’s essential that we accept diversity in stories which feature our collective experiences. Shows such as Lee Daniel’s Empire, and Mara Brock Akil’s Being Mary Jane, feature multi-dimensional LGBT+ characters which opens up a discussion in black households about LGBT+ prejudices, which unfortunately still prevail in black communities. Art is ground breaking and successful when it can speak to the marginalised within the marginalised, and shed light on difficult topics, from an insider’s point of view. Stories with these unique vantage points should be allowed to flourish.

A writer of colour’s community are the best barometer for how stories which feature them will be received. If something comes across as amiss or just “off” (BuzzFeed’s “black people questions” video comes to mind), we will always have critique, cryptic tweets and comment sections. However, communities need to give storytellers a chance to express themselves. There is a danger that writers are being policed on what they can and can’t portray, setting a dangerous precedent for artistic expression.