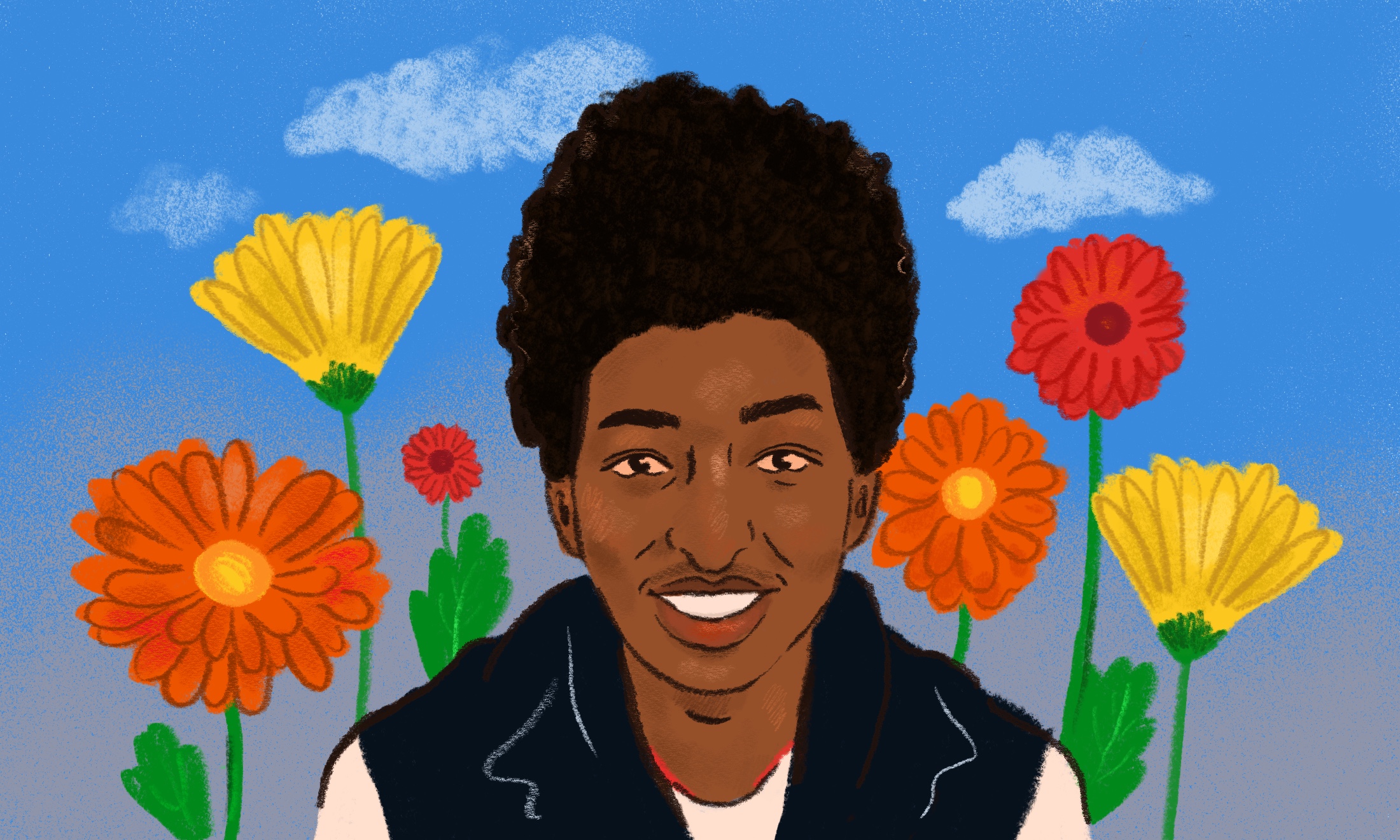

Aude Nasr

The trauma of bridging worlds as a child translator

Unpacking the heavy expectations placed on immigrant children who learn the language of their new homes far quicker than their parents.

Sanmeet Kaur

29 Apr 2021

In his novel On Earth We Are Briefly Gorgeous, Ocean Vuong pens a letter to his mother in which he writes: “I promised myself I’d never be wordless when you needed me to speak for you. So began my career as our family’s official interpreter. From then on, I would fill in our blanks, our silences, stutters, whenever I could. I took off our language and wore my English, like a mask, so that others would see my face, and therefore yours.”

When I first read this passage, it caught me off guard in a way a book hadn’t in a very long time. In it, I saw a reflection of my own childhood and was stunned that up until now, I hadn’t quite grasped the enormity of the burden placed on me as a child translator. And it’s something that continues to be the reality for many refugees and migrant children today.

Moving to a new country comes with many challenges and the need to learn a new language is often the key difficulty. As immigrant children begin to attend schools and other educational institutions, they often find it easier to pick up a new language. However this means that their parents can get left behind, and so they end up relying on their children to translate and interpret a foreign world.

“Parents can get left behind, and so they end up relying on their children to translate and interpret a foreign world”

My family fled Afghanistan when I was five and we arrived in the UK not speaking a word of English. It was hard enough coming to a new country as refugees, but not being supported to learn the language, we struggled with even the most basic things. Going to school meant that I picked up English much faster than my parents, but this resulted in an unusual role reversal of the parent-child dynamic.

Every time we left the house together, I did something I thought all children did: I spoke for my parents. All the adults in the room would be looking down at me, their faith placed in the arms of a five-year old to help bridge the gap between two foreign worlds. Having barely learned to string together a sentence, I now had to learn to do it in not just Punjabi, but also English. And I had to learn quickly.

The consequences of not picking up these skills were too dire to imagine so I stumbled and stuttered, and did what many desperate immigrant children often do. I had to fill out immigration and housing documents, accompany my parents to doctor’s appointments and mediate during parent-teacher meetings. I struggle to think who else could have stepped in. Coming to a new (and often hostile) country meant my parents trusted me to advocate for our family’s interests, rather than a professional translator.

Reflecting on those years now, I realise how jarring it was to translate the trauma my parents had experienced in our homeland, despite it being something I had yet to unpick myself. In immigration interviews, I had to detail the violence my parents had faced in Afghanistan as a religious minority, as well as our journey to the UK and the horror we faced at the hands of the people smugglers. It enrages me that there was so little support from the government when it comes to helping refugees integrate and pick up language skills, to the point where a child had to pick up the pieces. In some cases, immigrant children are having their childhoods chipped away by taking on such a responsibility that’s far beyond their years.

“I had to fill out immigration and housing documents, accompany my parents to doctor’s appointments and mediate during parent-teacher meetings”

I felt like I had to grow up very quickly. I remember going to all my mum’s hospital appointments when she was pregnant with my younger sister and at the age of 12, I had to translate everything the nurses said. Imagine being a child and having to translate to the GP that your mum is experiencing severe cramps. And then thinking “What is the English word for cramps? Will the doctor understand the severity of the pain I’m describing?” These are just some of the things that would go through my mind. I used to get really stressed about this because I found it embarrassing (except when it came to parents’ evening, when I’d absolutely take pleasure in translating lies to my mum so I didn’t get in trouble for talking in class).

It’s quite upsetting looking back at school reports as almost every single one of them notes how ‘mature’ I was. I had to be sensible because there was a family at stake. I couldn’t get in trouble at school because a detention after school would mean I’d miss my sister’s doctor’s appointment, which of course I had the responsibility of translating. One time, I had my baby sister on my lap as I was explaining how she was getting on, and the doctor referred to me as ‘mum’ and my actual mum as her grandma. I remember the sheer embarrassment I felt at that point, and resented my mum for not being able to do the simple task of speaking for herself.

But as an adult, I totally understand why I needed to do it – because the state had failed to provide this essential help. What we also really needed was mental health support to process what we had been through as refugees. On top of that, my mum was traumatised from the war in Afghanistan, so is it any surprise she didn’t want to go outside and learn English? In Kabul, as a woman and a religious minority, she was expected to stay indoors for her own safety. She would tell me that the outside world was a dangerous place for women. This fear was made worse by the fact that almost every time we went outside in England, we were faced with racist abuse, so staying indoors became the safer option for my family.

“My mum was traumatised from the war in Afghanistan, so is it any surprise she didn’t want to go outside and learn English?”

The thing I struggled translating the most was racist abuse, but even my mum would catch on and not ask me to translate. I appreciated this small unspoken understanding we had between us. Not everything needed to be reiterated.

As an adult, it breaks my heart to see the loneliness of not being able to speak the language of the country you’re in. My mum often wishes she had the chance to learn English and thinks it’s too late to learn now, as she’s already survived the last 20 years without it. But without the language skills, she also gave up a huge portion of her independence. Even a trip to the local shop by herself is terrifying: “What if someone says something and I can’t respond?” she’ll often ask me.

I was in a constant state of anxiety as a child – something that continues to deeply affect me now – the idea that my parents (and later on my younger sisters) were dependent on me really scared me and crushed me. Parents often want to conceal hardships from their children, but I was exposed to them all because I had to translate our family’s reality to various authority figures – whether it was the housing officer, immigration officer, teachers or GPs – I dealt with them all. Being my family’s lifeline to the outside world was essential to our survival, but it also shaped me in ways I’m only beginning to grapple with.