Photography via ihartericka's Instagram

The world according to Ericka Hart

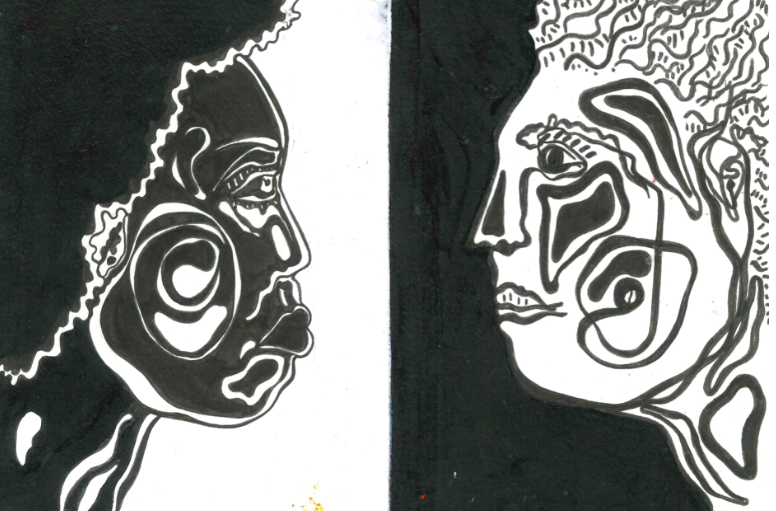

The activist-slash-educator is encouraging you to decolonise your mind and relearn everything you thought about sex, gender, and health care

The Triple Cripples

11 Mar 2020

Ericka Hart’s eyes glisten, as they sweep over the audience in the Library Lounge at The Standard, London. We are all present for their conversation with gal-dem’s founder Liv Little, waiting eagerly to hear their insights on sex and relationships. “PENIS!” Ericka calls and the audience tentatively responds, in kind. “VULVA!” and the staff in the venue, exchange looks and smirks. “PERINEUM!” we all call out, swept along by the defiance of Ericka’s enthusiastic and lighthearted warm-up to the discussion. Ericka has a bright aura, their curvy frame wrapped in rich blue denim. Their waist-length, golden box braids cascade down to their patent, cream, knee-length boots. Everything about Ericka is present and makes a statement.

Perhaps this is an after-effect of the path they found themselves upon after famously appearing topless at Afropunk in 2016. Ericka was thrust into the public eye. They did what no femme-presenting, black body should do – exist outside of the rigid, suffocating, dehumanising constructs defined for them by a white supremacist societal gaze.

Ericka Hart is a black New Yorker, sexuality educator and race, gender and social justice disruptor, amongst many other things. Their critiques of the medical industry, sexuality, social theory, gender and race, have gained respect in social justice circles and media. For those of us who live entangled within the margins, Ericka’s work has been instrumental in creating the necessary visibility, representation and understanding of our existence. It is not an exaggeration to say that them taking up space, and “being” boldly in their skin, has given rise to many activists and movements in online spaces. Indeed, were it not for Ericka and their partner Ebony’s unapologetic online presence, platforms like The Triple Cripples, may not have been as well understood or widely received. Ericka and Ebony are being themselves and refusing to bend or mould into preconceived ideas of gender, black love and black scholarship.

We interviewed the bold and beguiling Ericka, hoping to capture some words of wisdom, in the plush settings of The Standard hotel. Here, they unpack everything from sexuality and decolonising gender, to what it’s like to face a health crisis when you’re black:

On realising difference in childhood

“I’ve been thinking about young Ericka a lot, these days. Young Ericka was very inquisitive. Things that are not a big deal to a lot of people, were a big deal to little Ericka. Why does my hair stand up and the white girl’s does not? Why is my nose large, but theirs is not? My belly button – I used to have an outtie and I used to question even that. Like, that was racialised for me, because no one else had an outtie. I just had a lot of questions that I would ask. And I was always asking them, so that was me as a kid. Just very inquisitive.

I grew up with two acres in my backyard. I would just be in the woods for most of the day. I would just be back there with the trees and all the plants, picking berries, it was my own little imaginary world. Which was a break from living in a predominantly white neighbourhood.”

On whether homophobia is a black issue

“White people are [also] homophobic. White people [may] not talk about sex in their families. So, the thought that they do is a function of white supremacy –here they get to not talk about it, but it is also perceived that they do. It has a lot to do with black people being underneath a microscope, and it being like, ‘Oh, y’all are very homophobic’. Because a few people on maybe television, have been homophobic, that now means that black people are homophobic? No, no, no. Just because there’s a lot of white gays on TV, does not mean anything about the ‘white community’, if you will. Is there even a ‘white community’, anyway?”

On breast cancer and medical bias against communities of colour

“The way that people talk about how black people die at higher rates from breast cancer than white people, is as if there is a gene that kills black people faster from breast cancer than white people. No –lack people access mammograms just as much as white people. However, the mammograms that we access will be wrong –doctors will tell us wrong. They won’t give us the pain meds that we need or the care that we need.

For so long people told me when I was in my twenties, ‘You don’t need to get a mammogram just because your mum had that history –you don’t need it’. Could you imagine if I didn’t actually find a lump? There’s no gene that’s different for us. It is all about access. It is all a function of a social issue that keeps us from living, not a biological one.”

On systems of oppression and sexual expression

“Systems of oppression directly impact our pleasure and our sexual life. I think if people actually understood that racism, classism, ableism, transphobia and femmephobia, directly impact our sexual expression – then they would actually understand sex. I think people try to put the cart before the horse. You have to talk about how your body has been regarded as a black person, before you fuck, before you start talking about who you’re attracted to. My sister said to me the other day, ‘I’m sorry, Ericka, but I’m attracted to white people’. I said, ‘you don’t have to say sorry. Just understand that you’re attracted to white people because everything around you says that you should be attracted to white people, Okay?’. So understanding that.

I was married to a white person – if I would have had that understanding, I would understand my body so much better. Through the lens of blackness, rather than through the lens of whiteness. And I think that that would free so many people. It’s not separate. It’s not a Sex Ed curriculum ‘…and then here’s the chapter about black people’. It’s [needs to be] throughout the whole thing.

On decolonising gender

“I think it’s important for black people to explore gender on our terms. [For] people descended from the slave trade, it’s put on us [by the white gaze] that if you’re a black femme – you’re strong, you’re supposed to give, you’re supposed to be a caretaker/mammy for everybody. If you’re a black cis man – you’re supposed to fuck everybody and have a large penis.

There’s a great article written in Afropunk blogs, it’s called “My Gender Is Black”. It talks about how somebody [seeing] them is always going to relate to them as black [regardless of] their expression of their gender. So, I think that us talking about that and exploring what that means, as a paradigm for gender, rather than using what white folks have said is gender, would actually be decolonizing.

This interview has been edited and condensed