I was silenced when I spoke out about the abuse I faced in underground music circles

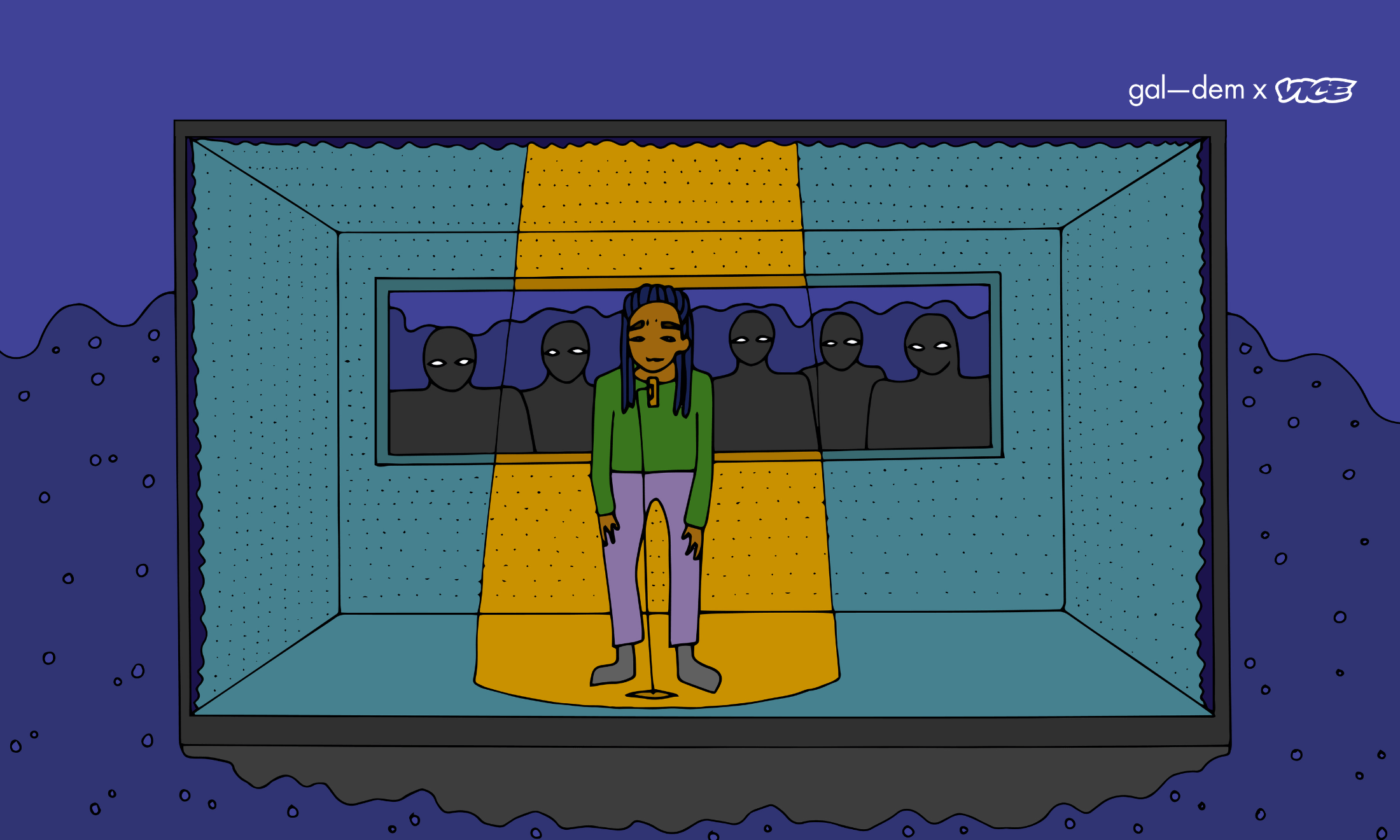

When they were starting out in music, this DJ was assaulted by someone else in the scene. But upon reporting it, they were left feeling even worse.

Anonymous

25 Jul 2022

Aude Nasr

This article is part of Open Secrets, a collaboration between gal-dem and VICE that explores abusive behaviour in the music industry – and how it has been left unchecked for too long. Read gal-dem’s Open Secrets articles here, and read VICE’s Open Secrets articles here.

Content warning: This article contains mentions of suicide and sexual assault.

Healing after trauma is the goal. To be free of your past, to start anew, with a fresh beginning somewhere and just chill. But I can’t because the cause of my pain is all around me. I try and shake it off and I fail.

When you’re sexually assaulted, a common silencing tactic is your abuser telling you no one will believe you. We live in a society where the word of a man is believed over that of marginalised genders, and the word of a white person is believed over that from a person of colour. The general consensus is that if you’re raped as a Black woman or femme and the perpetrator is white, you’re a liar and you deserved it. Even though the historical origins can be traced throughout slavery, those with power are the ones who dictate who matters and who doesn’t.

At this moment, you’re reminded your place in society is at the bottom. And no one gives a shit. What happened to me isn’t unique. It’s the result of hundreds of years of violence and continuous mistreatment of bodies that look like mine to preserve the status of those who are the direct opposite. In society’s eyes, I can’t be a victim. I’m not small, I’m not blonde, I’m not cisgender, I’m not white, I’m not straight and I’m not middle class – I am so far removed from the binary that most of the people who engage with me on a daily basis don’t know how to.

“In society’s eyes, I can’t be a victim”

Black bodies are seen as a commodity – we’re either an enslaved labour source or fetishised. We’re not seen as people, but bodies of material matter to be consumed. Through this process of dehumanisation, abuse towards us is normalised. It becomes so entangled with daily life that no one blinks an eye – it’s just something that happens by chance rather than the result of structural inequality. So when the conversation surrounding abuse in music resurfaced in summer 2020, at the same time as the Black Lives Matter movement, naturally the intersection came to a head. Both the #MeToo and BLM movements were started by Black women. We’re seen as the saviours – it’s our role as women and femmes to be the mammy, to save society under any circumstances, despite being the most affected, and despite the abuse and suffering we go through.

I vaguely remember how I ended up in an ambulance to A&E. I called a friend of mine in a panic after swallowing as many antidepressants as I could and she came from wherever she was and called 999. This was the first of nine attempts that would take place over the next seven months. I remember every single second before trying to overdose and not much after. The endpoint was calling out my abuser, someone also involved in music, on social media. Though there had been a period where women were demanding to be heard, to be listened to and for accountability for the actions of abusers, soon after, I had several messages from strangers calling me a liar, telling me I deserved to be raped; most were saying I should kill myself, some claimed I invented the whole relationship and I had a personal vendetta.

“Black bodies are seen as a commodity – we’re either an enslaved labour source or fetishised. We’re not seen as people, but bodies of material matter to be consumed”

When you’re in your early 20s and just starting out in music, it is terrifying enough. I’m generally shy and awkward but I love to party and that’s all I wanted to do. But clubs, despite their perceived counterculture and resistance against white heteronormativity, are currently unsafe for marginalised people. Add this to masses of people creating fictional stories, adamant I was lying and using every single stereotype of the Angry Black Woman they could, it was clear the abuser and their friends weren’t going to stop till I remained silent.

Having people call me a liar, some even writing false police statements or shouting at me in public, is enough to cause anyone a breakdown. But there is something particularly insidious about abuse in underground music circles. Those controlling and owning the spaces, booking artists and controlling the discourse are those with power and privilege. They look and act exactly like those controlling the overarching structures, but cloaked in trendier clothes and neo-liberal buzzwords. Once I spoke out, I was automatically blacklisted. A lot of people I cared about deeply stopped speaking to me and I couldn’t attend events without people staring, gossiping about me within earshot – so I stopped going out.

“There is something particularly insidious about abuse in underground music circles”

I had not been DJ-ing for long at this point and I was pushed to quit for my own safety. Even at clubs with safe space policies, I’ve been harassed. I’ve played gigs where I’ve been groped behind the decks, shouted at by the promoters’ friends and been told to “agree to disagree”. Sometimes, I’ve simply not been allowed in because I “don’t look like a DJ”.

Marginalised bodies are the targets and subjects of abuse. Navigating the world simultaneously as both hypervisible and invisible allows for emotional, physical and sexual abuse to happen seemingly unnoticed. This unnoticing is intentional. I’ve been in clubs and I’ve had men put their hands up my skirt, white women grab my chest and laugh with their friends, gay cis men grab any part of me they can get hold of and then get angry when I ask to be left alone. There are layers to this violence. There is no one to protect you. Bouncers do nothing but shrug it off and ask if you would like to leave – as if you’re the inconvenience. Very few promoters stand by their own policy because it’s a “vibe ruiner” for their friends and the crowd follows the lead of those around them. The police are particularly dismissive – historically, barely any rape / sexual assault cases are referred to CPS for review but, while the numbers for convictions are low, in reality, the abuse is high.

“There are layers to this violence. There is no one to protect you”

As soon as I reported the abuser, I was subjected to police questioning. This was essentially uniformed men and women severely gaslighting me and my experiences. One of the officers called me a “liar”, a “bitch”, saying I was “making it all up and trying to ruin a good white man’s life”. I had no desire to even report the assaults to the police but with large groups of people adamant their friend was innocent, despite other women coming forward, I had to. The abuser’s behaviour became so part of my routine, I was already numb and distant most of the time. So when the situation, which was public, unfolded and I was mostly left unsupported by a community who prided itself on protecting each other and championing the marginalised, I retreated more into myself and couldn’t find any reason to keep on living.

Every day I’m reminded of his actions and those of the people who knew what was happening and chose to remain silent. Of the people who profited off Black culture, while turning a blind eye to the abuse carried out by their friends. This is how the collective lack of accountability is maintained – it manifests itself in everyone around you and the harm caused becomes the norm. Every violation against you is normalised when no one speaks up. One of the most painful realisations is the feeling of loss. The loss of agency, the loss of nearly eight years of my life, the loss of my inner light that guided me throughout childhood. The end result for me was a diagnosis of Complex PTSD, depression, agoraphobia and crippling anxiety. I still struggle daily. But the feeling I can’t yet overcome is the sadness and disappointment I feel in every person that could have prevented this and didn’t for the sake of their careers over my own humanity.

For a full list of resources related to this article and the Open Secrets Series, visit our Open Secrets Resources page here.

Our groundbreaking journalism relies on the crucial support of a community of gal-dem members. We would not be able to continue to hold truth to power in this industry without them, and you can support us from £5 per month – less than a weekly coffee.