Karis Crawford

‘This ain’t a thing we do round here’: Travis Alabanza on lipstick, shame and growing up

In an extract from their new book, None of the Above, Travis Alabanza recounts a pivotal moment from their teenage years.

Travis Alabanza

04 Aug 2022

Content warning: mentions transphobia and homophobia

I am 15. My version of 15 means by now I have already smoked too many cigarettes, thrown up six times on four friends’ couches and had enough sex to think I’m an expert sex advice columnist. At 15 my face has started to look a lot older, I feel more confident swearing, and sneaking into gay bars underage means that I am starting an accelerated process in figuring out who I am.

Also, most importantly to this part of my story: I have accepted I am someone who was assigned a boy at birth – a Black boy at that – but who enjoys wearing lipstick and trying on dresses. The shame that surrounded me at 14 is disappearing. I note this because I think it is important to tell you that in the moment I am writing of, I am 15, not 14.

Fourteen was different. At 14 I was writing poems in my diary about trying to disappear. I was struggling with what wearing make-up and dresses meant to my morality – and mortality. I spent hours screaming into the mirror that my life was over because of my urges to replace my tracksuit with a sequinned jumpsuit and gold hoop earrings. I was never brave enough to buy my own lipstick, yet spent hours fantasising about stealing my mother’s ‘special occasions’ dark red Mac lipstick in her bedside drawer. Fourteen was a time of agony. But that was 14, and I am telling you now that I am 15.

“I was never brave enough to buy my own lipstick, yet spent hours fantasising about stealing my mother’s ‘special occasions’ dark red Mac lipstick in her bedside drawer”

At 15, I have stopped screaming into the mirror. I have bought that black jumpsuit with the first pay cheque I received from the café I work at. My friends are starting to teach me the importance of eyeshadow, and what shades look best on my brown skin. I tell you this not because I am wanting to indulge in how or where I found my confidence. That is not the theme of this chapter: the theme, or rather the problem, in this chapter – the problem I had when I was 15 – is not self-acceptance, but others’ doubt.

Of course, this does not mean that self-doubt does not creep back in – I have my late teens to come – but 15 is a time I remember so vividly as holding little shame. Yet that did not stop others’ reactions to me. So often, the fixation with gender-non-conforming stories is whether or not we believe in ourselves. A neoliberal hijacking of gender politics has generated commercials and media interviews with us, giving our best tips on how to ‘love ourselves’, as if we can love ourselves out of systemic oppression.

This feeling at 15 had nothing to do with my lack of self-belief; I am 15: I have found at least some form of self-acceptance. Actually, self-acceptance feels too flimsy a word. Too many Instagram captions and blog posts have made the word feel like watered-down paint. At 14, I was wondering if I was possible; at 15, I knew I had to be. At 14, I was clinging to black and whites; at 15, I was embracing and stumbling into the richness of full, saturated colour.

‘What the fuck is that on your face?’

The shopkeeper, who has been at my local shop all my life, asks me this, in the middle of a busy store full of my community. Mothers, aunties, school friends, the girl who is always on her phone, the guy who works in the laundrette, who two years later I will suck off in the back room.

I grew up in one of those council estates where the corner shop is also the church, the meeting place, the babysitter, the vets, the hangout spot and the exchange centre all in one. The corner shop, in a place where the nearest grocery store is over 15-minutes’ walk, becomes a well-populated cross-section.

I have not been back to my council estate in years, and if I was more invested in the accuracy of this imagery than my own mental health, I would have walked back there for writing this book. I always thought I would. I imagined a cinematic homecoming where I return to take notes on the place I spent the first 18 years of my life. Dressed in a chic investigator’s outfit, I would ignore how hard that return may feel, so I could describe accurately how the bricks were more of a rusty brown than a bright orange. Or how the bus stop pole had a bit of graffiti that said ‘batty boy’ on it that you could not miss.

“At 14, I was clinging to black and whites; at 15, I was embracing and stumbling into the richness of full, saturated colour”

But unfortunately, I cannot do that. Maybe it is resentment, or fear, or something I haven’t yet identified – but there are too many things blocking me from returning. In my memory, it still looks like every other council estate you have seen. Maybe on my return I could have found the specific red within the brick, or remembered which letter was sometimes missing on the bus stop sign, or the particular mixture of smells that came through the neighbouring gardens.

There were the essential pillars holding up the shape of our council estate: a corner shop, a chippy and a green that I used to play on as a kid until I became too feminine to feel safe to do that. It took an hour to get into the centre of town, on a bus that would try to run every 30 minutes but would always be late. The estate housed a mixture of Black, South Asian and white families – in varying degrees of poverty – and the odd family that had been promised this area would be the next up and coming thing, which of course never happened.

We owned our council house, because my dad had bought it for us before he left. I think he fell into the category of people who thought the area would become something. Yet without a dad in the picture, and just Mum working as a receptionist to support two kids, we now sat in the varying degrees of poverty bracket that enclosed the estate.

‘What the fuck is that on your face?’

I remember I am 15 now. I am embracing the richness of my colourful paint. I am real. This is my corner shop, like it’s everyone else’s.

‘It’s lipstick. I bought it with my own money.’

He says the next phrase almost without missing a beat. Without any pause to remember he knows my mother, my neighbour, my school friends, the girl who is always on her phone, the guy who works in the laundrette, who two years later I will suck off in the back room.

‘This ain’t a thing we do round here, son.’

I have to pause, to make sure I have heard it right. I cannot believe a man I have known for so long would say this to me, in front of everyone. I am yet to be of an age where a man’s betrayal is like the background score to my life. Status works differently on estates, and I am working hard to try and survive the increasing number of heckles I receive whilst waiting for the bus, or the growing rumours that I am going into town to go to gay bars. It has been working because – until this point – no adults have been involved, which equals my mum not knowing any of this is happening. The ‘this’ here meaning other people’s anger, not my own identity.

I am not worried about my mum reacting to my queerness, more that she has enough on her plate to worry about, without adding my safety to it, so I have always assured her there is no danger with a confidence I have learned to perform – one that exudes ‘I am absolutely in control’. Secrecy, in my eyes, equals safety – and this shopkeeper saying this phrase feels anything other than secret.

‘This ain’t a thing we do round here, son.’

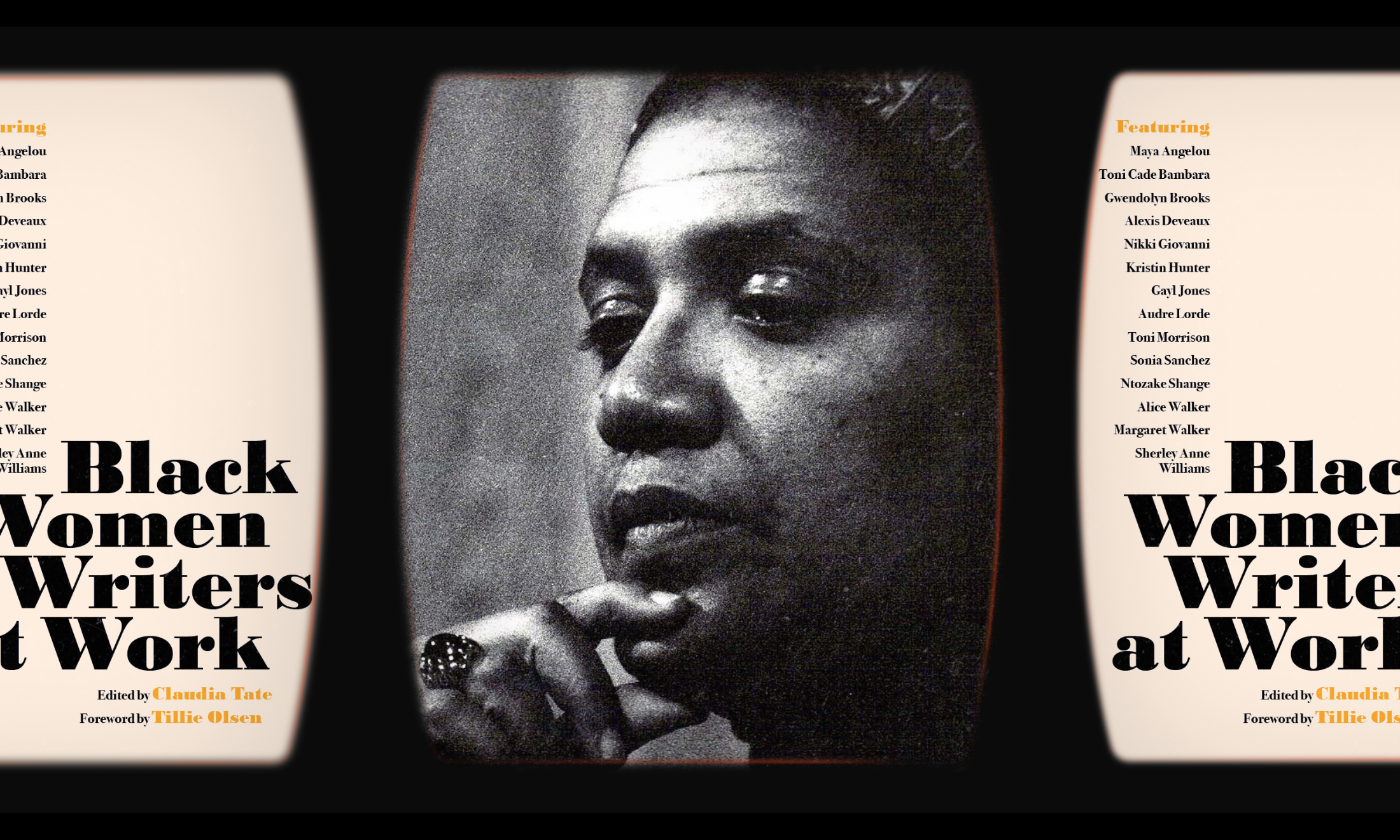

None of the Above: Reflections on Life Beyond the Binary by Travis Alabanza is published on 4 August by Canongate Books. It is available via Waterstone’s Online.