UK universities are adopting controversial IHRA antisemitism guidelines – but it’s putting Palestinian solidarity activism at risk

The UK government has threatened sanctions for universities that don’t adopt the IHRA definition of antisemitism, placing students and academics fighting for Palestinian freedom under attack.

Hadeel Himmo

23 Aug 2021

Diyora Shadijanova

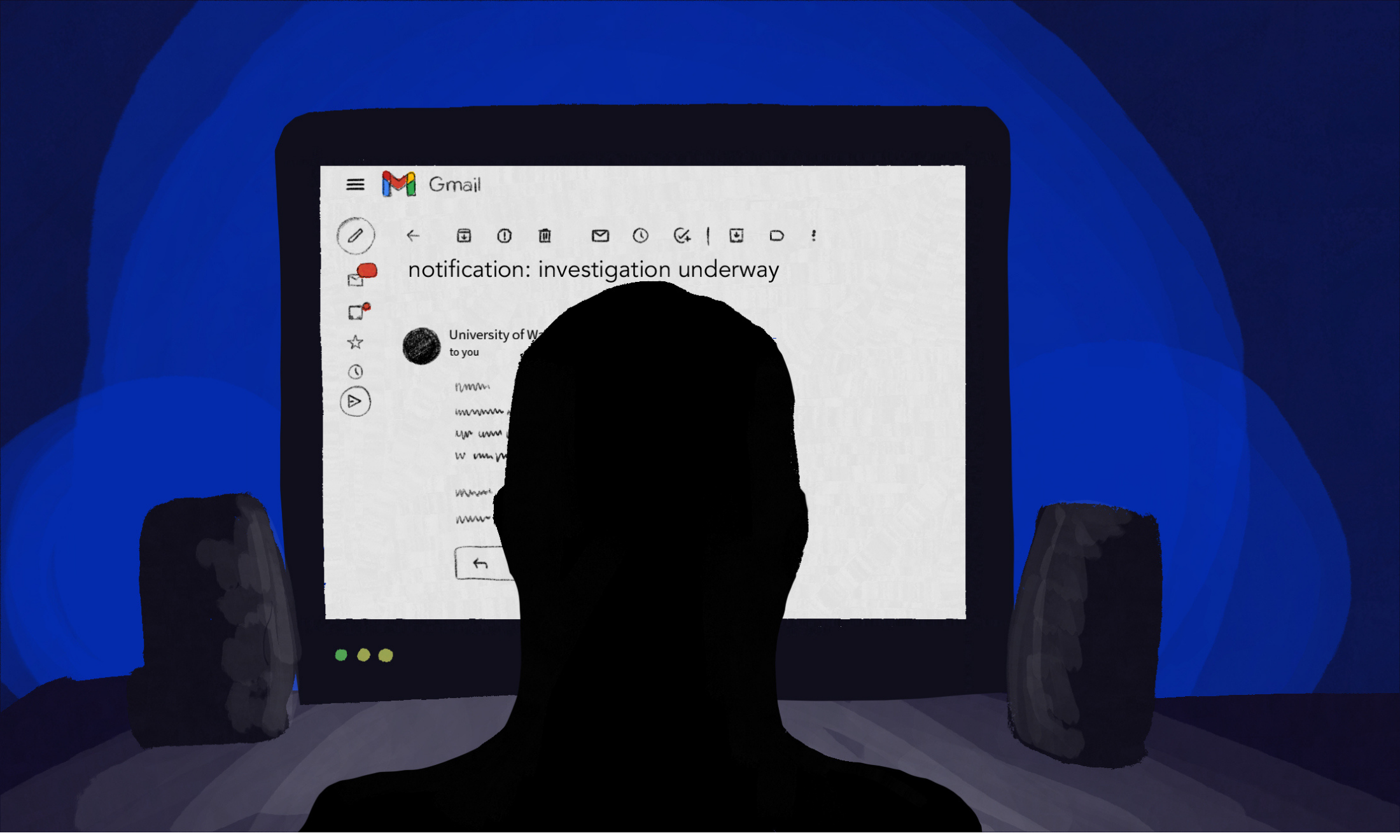

When 21 year-old Yasaman* became involved in student activism at the University of Warwick, they were hoping to make a change and meet some like-minded people. Over the course of their studies, they duly threw themselves into meetings, organising campaigns and events. But just before their third-year assignments season began in May 2021, Yasaman opened an email from university authorities.

They were being investigated for antisemitism, the missive informed them, for a post they’d ‘liked’ on Twitter in 2017 reading “Palestinians declare Washington DC as the capital of Israel”, a satirical tweet mocking Donald Trump’s then-declaration that Jerusalem was capital of Israel. The university did not provide any explanation as to why ‘liking’ the post was antisemitic, but did reveal that the complainant was a fellow student. Yasaman had their suspicions about what might motivate their peers to go digging through their historic Twitter activity: because they were an active member of Warwick’s pro-Palestine movement.

Since 2020, universities in the UK have been under pressure from the government to adopt a contentious definition of antisemitism, penned by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. Forty-eight universities have adopted it in some form at last count, including most of the institutions making up the ‘elite’ Russell Group. Warwick chose to adopt the definition in October 2020. The mode of adoption has varied; some universities have chosen to implement the definition as formal policy, others as guidance, and some with the examples suggested by the IHRA.

The problem with the IHRA definition of antisemitism, say critics, lies in the fact that its conflation of Zionism and Judaism stifles critique of the state of Israel. While the definition initially defines antisemitism as “a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred towards Jews”, it is accompanied by eleven ‘illustrative’ examples, some of which focus on Israel – and much of the controversy surrounding the definition focuses on the adoption of the definition with all of its examples included.

According to the IHRA’s associated examples, it could be antisemitic to claim the “existence of the state of Israel is a racist endeavour” or “[apply] double standards by requiring of [Israel] a behaviour not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation”.

In defence of the definition, in May 2021 a coalition of Jewish students wrote in The Guardian that the IHRA guidelines “protect” them and that the definition does allow critique of Israel – so long as it is on a similar level to that of other states.

However, in an open letter published in the same outlet in November 2020, 122 Arab and Palestinian academics, journalists and academics outlined the pernicious ways the wording of the definition could be used to stymie critique of Israel and its racist structures. They also highlighted how the IHRA definition had been disproportionately deployed to silence leftwing pro-Palestine groups, while ignoring blatant antisemitism and the rising threat from the white far-right in Europe.

“There is a huge difference between a condition where Jews are singled out, oppressed and suppressed as a minority by antisemitic regimes or groups, and a condition where the self-determination of a Jewish population … has been implemented in the form of an ethnic exclusivist and territorially expansionist state,” they wrote.

Antisemitic incidents on campus have seen an increase in recent years; a 2020 report from the Community Security Trust (a group that supports the IHRA definition) found that there had been 65 instances of antisemitism reported in the academic year 2019/2020, compared to 58 in 2018/2019. The majority of incidents took place online. However, questions have arisen about the IHRA’s effectiveness in tackling campus antisemitism without conflating it with anti-Zionism and costing another group of oppressed people their voice.

Surveillance culture

Upon opening the email from the university and reading that they were under investigation, Yasaman was filled with dread. “It felt like all forces were already set up to be against me,” they tell gal-dem. “I had already struggled for the past three years to navigate an institution where the PREVENT agenda prevails. The investigation exacerbated these feelings; it feels like universities are becoming mini-surveillance states targeting people like me.”

The ensuing investigation against Yasaman lasted two months. During that period, Yasaman says they were “left in the dark” by the university about what the consequences would be if they were found ‘guilty’ of antisemitism for ‘liking’ the tweet.

Yasaman’s dissertation, which was comparatively studying settler-colonialism in Palestine and Kashmir, was due soon and they felt they had to begin censoring themselves in essays for fear of further investigation. Though they ultimately decided not to give into self-censorship, Yasaman could not shake off the feeling that they were being surveilled from all angles.

Not only did Yasaman have to continue preparing for their end of year assignments with the investigation hanging over them like a dark cloud, they also were left shouldering the extra burden of finding legal support to help fight the accusations.

Eventually, the investigation against Yasaman was dropped; Warwick authorities ruled it was moot because they had ‘liked’ the offending tweet before becoming a student at the university. But the decision was of little comfort to Yasaman who knows timing is all that prevented them from being tarred with the brush of antisemitism. Now they fear how the IHRA definition can be used to silence fellow students active in support of Palestinian rights or speaking out against Zionism. And, judging from testimony filtering in from other UK institutions, this fear is not unfounded.

“I feel gaslit about my family history. The Nakba isn’t some purely political and historical event, it’s a personal reality for all Palestinians”

In May 2021, Cambridge University Labour Club expelled a member who had published an article criticising the IHRA definition. The piece, the CULC said in a statement, was “grossly detrimental to the club’s reputation”, with the organisation adding they had been “proud” to adopt the IHRA guidelines.

At no point did the CULC actually clarify what the offensive comments had been and academics spoke out in defence of the penalised student, with Oxford historian Marc Mulholland writing: “Whether one agrees or not with everything in this article, it is obviously written coolly and with due scholarly consideration. There is nothing inflammatory in it. It’s quite incredible that it led to the author’s expulsion from Cambridge Labour Club”.

Amal*, a 22 year-old Palestinian postgraduate studying at Queen Mary, University of London says that “honest discussions around the Nakba [the displacement of Palestinians in 1948] have been set aside” as a result of the definition.

“I think that people are uncomfortable hearing about the Nakba and Zionism now,” Amal adds. “I feel gaslit about my family history. The Nakba isn’t some purely political and historical event, it’s a personal reality for all Palestinians. My father is 83 years-old and yet I can’t openly talk about his experiences of Zionism or draw any conclusions – like call Zionism racist – without it being overridden by this definition.”

For Palestinian students in particular, many have reported feeling that this effectively prevents them from discussing the oppression and violence facing Palestinians, even with the attacks by Israeli forces claiming the lives of 200 Palestinians in just one week in May.

Since the IHRA definition was introduced at Queen Mary in 2020, Amal has been afraid to speak up about her family’s experiences in Palestine. “I feel as if there’s a greater risk to me speaking out,” she admits. “I feel as if Palestinians are placed under a microscope when it comes to antisemitism and that is quite scary.”

One of the IHRA definition’s authors, Kenneth Stern, has said that “it was never intended to be a campus hate speech code”, yet growing concerns over its implementation in the UK suggest otherwise.

The IHRA definition’s impact on the Palestinian movement

The battle surrounding the IHRA definition, and attempts to paint Palestinian solidarity activism as antisemitic, force Palestine activists into a constant state of defensiveness, say those on the ground. Such weighty accusations keep individuals and groups stuck in the never-ending cycle of having to react to and defend themselves against being smeared as antisemitic.

Joseph, a Jewish activist at the University of Birmingham, emphasises this effect of the IHRA definition: “In the eyes of many, the freedom of Palestine cannot be spoken about without pre-fixing with, or centring, antisemitism,” he says, adding that the IHRA definition “hinders an unapologetic resistance to racism, settler-colonialism and apartheid”.

Activists who spoke to gal-dem reported that adoption of the definition is limiting political action against Israeli settler-colonialism on campus. In 2020, Yasaman was involved in a successful attempt to pass a divestment motion through Warwick Students’ Union – committing the Union to lobby the university to end investments in environmentally harmful corporations, alongside arms and construction companies, such as BAE Systems and JCB.

However, the motion is being challenged by UK Lawyers for Israel (an organisation currently under scrutiny for their role in causing a statement of solidarity for Palestine being removed from a Manchester gallery) for violating the IHRA definition because it cites Israeli apartheid. Since then –– an entire academic year later –– the motion’s proposers have still not been able to launch divestment campaigns against the mentioned companies due to ongoing threats.

“As a member of the Jewish community I feel I have a duty to resist a weaponisation of antisemitism that is used to delegitimise any support for the Palestinian struggle”

Targeting Palestinian solidarity activism through legal threats against BDS/divest motions in UK universities is not uncommon among pro-Israel campaign groups. “Although such legal challenges are weak, student unions will follow suit because they are worried about the word ‘discriminatory’,” says Yasaman. They also noted the contradiction that, when the issue is discrimination against Palestinians, universities “are actually all stakeholders in this discrimination, as we can see through universities’ investments in companies violating Palestinians’ rights.”

For some Jewish students and groups like Jewish Voice for Peace who support Palestinian freedom, the IHRA definition also poses problems, as it perpetuates the idea that the Jewish identity is synonymous with support of Israel and its political policy. For Joseph, the definition “masks the reality that a fight against antisemitism is a fight against all forms of oppression and discrimination” and “manifests a divide between Jewish and Palestinian solidarity”.

“It is appalling that my experiences of antisemitism and my Jewish identity are homogenised by Zionists to fuel a supposedly ‘moral’ justification for an illusionary ‘democracy’ premised on the ongoing ethnic cleansing of Palestinians,” says Joseph.

“As a member of the Jewish community I feel I have a duty to resist a weaponisation of antisemitism that is used to delegitimise any support for the Palestinian struggle”.

Academic freedom under threat

It’s not just pro-Palestinian students at risk under the IHRA definition. Nicola Pratt, an academic teaching a module on Palestine in the University of Warwick’s politics department, said that fears around being accused of antisemitism for critique of Israel are affecting university educators.

“I have become anxious about discussing particular topics in my module, such as an article that compares Israel and Apartheid South Africa,” she says. “The IHRA definition gives students a license to complain against staff and other students who express critical stances on Israel and Zionism.”

Regardless of whether complaints lead to adverse rulings from the university, the result is a “chilling effect” and “will undoubtedly lead to self-censorship, particularly amongst students and early career academics who do not yet have a permanent job,” says Nicola. Right-wing campaigners have successfully created a panic surrounding supposed infringement on their academic freedom – yet when it comes to Palestine, they actively support censorship measures.

Perhaps doubly worrying is that the IHRA definition is coming into force on UK campuses at a time when awareness of the Palestinian struggle among young people is higher than it has been in recent years, as evidenced by the massive protests that erupted in May 2021 in support of Palestinians in Jerusalem and Gaza. “[The definition] is a shield of impunity for Israel on university campuses at a time when more and more people and organisations are recognising that Israel is a settler colonial state and is practising apartheid,” Nicola says.

Academics and students alike fear the silencing application of the definition will obstruct both accurate historical and political analysis in the educational sphere, and negatively affect the pro-Palestinian causes within student activism spaces.

Resistance in the lecture halls

Of course, in the wake of increased pro-Palestine awareness, attempts at IHRA-backed suppression are being resisted by many students and academics. In January 2021, a group of UK lawyers objected to Gavin Williamson’s attempt to impose the IHRA definition on universities, writing that the threat of sanctions was “legally and morally wrong”. Last year also saw hundreds of UK students add their names to a statement by the Palestine Solidarity campaign, outlining the issue of Palestinian students and allies being silenced by the adoption of the definition.

Over the last year, there have been debates over adopting the definition at universities across the country, including University College London, SOAS, City University, and at the University of Warwick. Students – and, in some cases, academic staff – at all four universities in these cases voiced opposition to the definition. At several institutions, student unions have voted to reject adopting the guidelines; in some cases – such as at City – university authorities decided to impose them regardless.

And the IHRA definition is not the only option for tackling antisemitism on campus. Alternatives are being offered; scholars in the fields of Holocaust history, Jewish studies, and Middle East studies have drafted a different definition to adhere to, called the Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism. Though some have critiqued this version, others feel it is a much better attempt at tackling structural antisemitism without infringing on the freedom of those who oppose Israel’s regime and/or Zionism.

Though many universities have adopted the definition, the situation is still unfolding as academics and students continue to organize to resist this suppression of the Palestinian and solidarity movement.

What is crucial is that opposition to the IHRA definition’s censoring elements continues to be voiced. “Most importantly, the Palestinian movement must reject falling into a discourse that is merely reactive to, and centred around, antisemitism allegations,” says Amal, firmly. “The movement must set the terms of engagement that center Palestinians in exile and the Palestinians living under occupation in Palestine”.

*Names have been changed to protect identities

If you have been affected by the issues in this article, The European Legal Support Center specialises in providing legal support and advice to Palestinian rights advocates across Europe and the U.K.

This article was amended on 24 August. An earlier version misstated that according to a 2020 report from the Community Security Trust, there had been 65 instances of antisemitism, according to the IHRA’s examples. While the Community Security Trust’s data includes entries that would only be considered antisemitic according to the IHRA examples on Israel, not all 65 instances necessarily fall into that category.

Like what you’re reading? Our groundbreaking journalism relies on the crucial support of a community of gal-dem members. We would not be able to continue to hold truth to power in this industry without them, and you can support us from £5 per month – less than a weekly coffee!!

Only by abolishing colonialism will Palestine be free

Shireen Abu Akleh: the voice of Palestine who refused to be silenced

Turns out the West understands boycotts, sanctions and divestment when it comes to Russia