Nobody warns you how difficult it is to step into and find your footing in diaspora. I emigrated to Canada from Patiala, India with my family in 2003. I was 10 years old and, in many ways, not yet ready to let go of the safety of my home and childhood. We settled in Winnipeg, whose Prairie-flatness resembled and often filled in for the Punjab of my feelings. Growing up as an immigrant in predominantly white communities, I wrestled with my identity and sense of place. In recent years, I have been able to sift through my internal diasporic storm by coming into contact with the creative work of other women, who have lived with their own histories of displacement and movement.

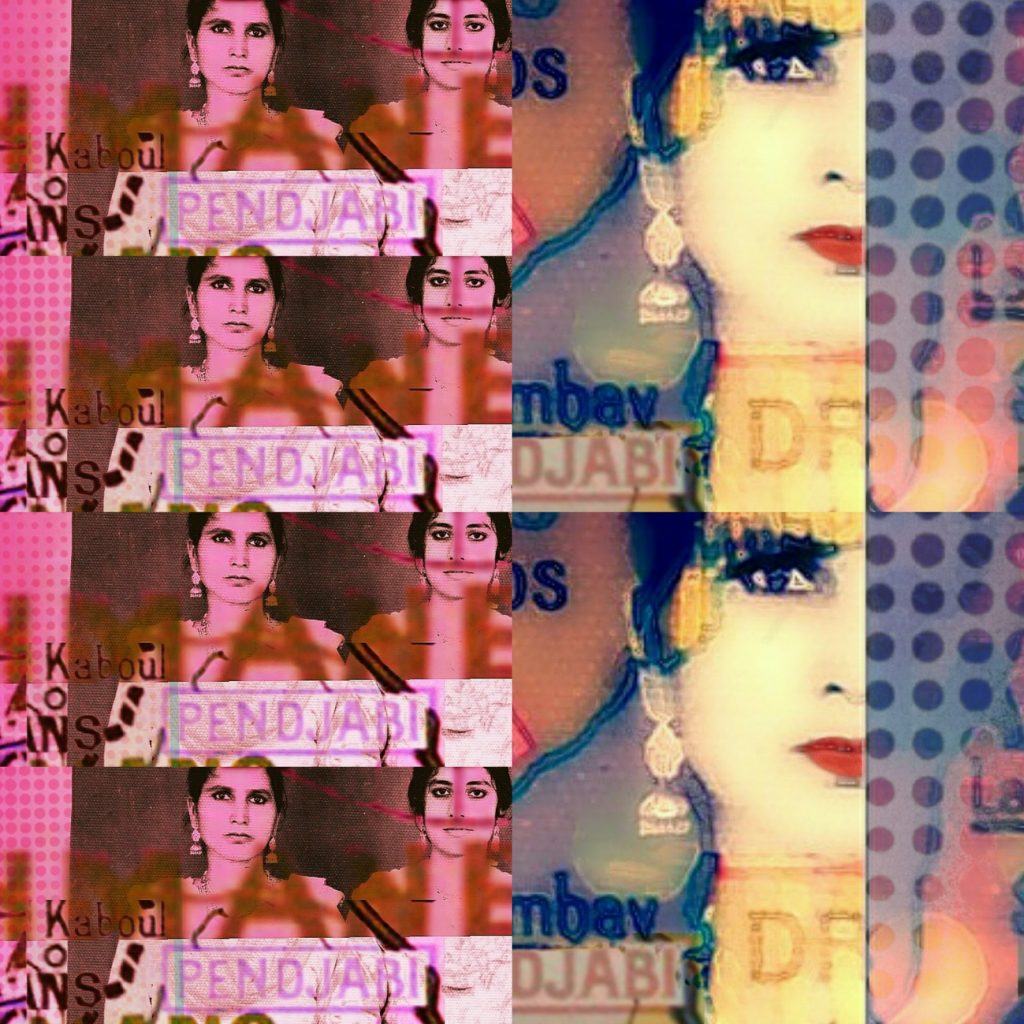

Angela Aujla is a Toronto-based artist working in drawing, digital collage and mixed media. I’m particularly drawn to her digital collages, which feature the bodies of Sikh women, sometimes floating and at other times secure in Canadian history. She takes up the project of archival rummaging through the appropriation of black-and-white family photographs. Following the advice of the Sikh poet, Amrita Pritam, she brings up stories, “not written on paper, but [those that] are written on the bodies and minds of women.” Bodies of Sikh women in the 1960s are abstracted, filled in, built upon, or coloured in for contemporary audiences, especially Sikh women like myself, so that we can see ourselves, “reflected in her portraits”.

Artists and communities of colour’s desire to repurpose familial and cultural objects can be tied to a broader “archival impulse”, (a phrase coined by American art historian Hal Foster). Appropriation and repurposing of found images, often from our own families as is the case with Angela Aujla, allows us to make “lost or displaced” historical moments “physically present.” This archival rummaging process helps us decolonise historical narratives passed down to us as immigrants and children of immigrants.

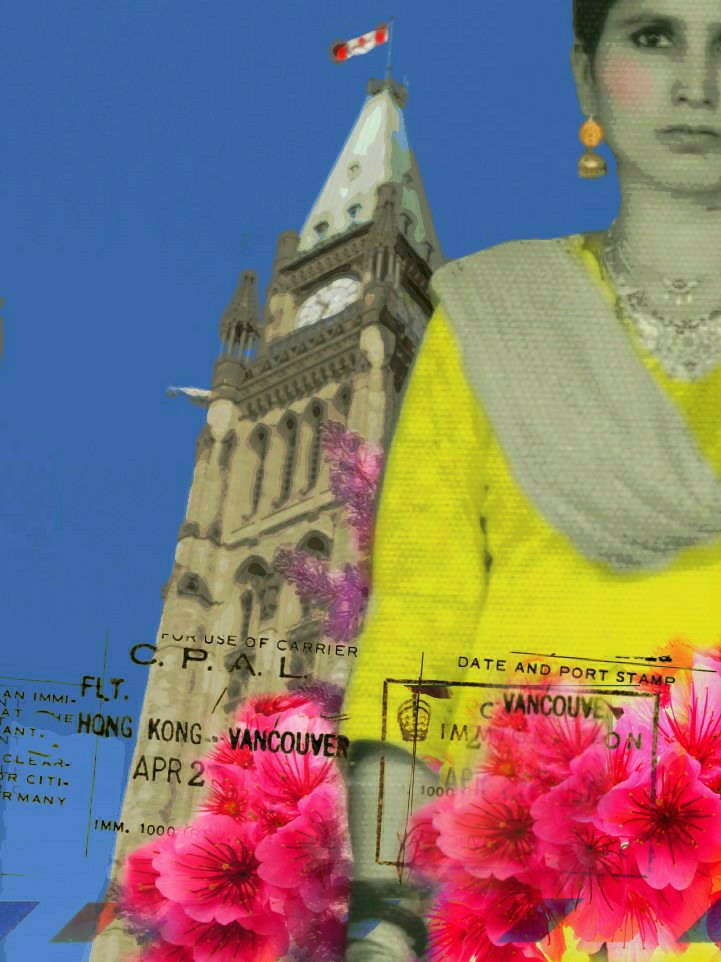

Becoming Canadian Revisited (2016), Angela Aujla, Digital Collage

Becoming Canadian Revisited (2016), Angela Aujla, Digital Collage

Through her work, Aujla visually guides us through our own histories rather than asking us to take a stand against them. In other words, we are put into dialogue with instead of in opposition to Canadian history. The work, Becoming Canadian Revisited…, frames a woman’s body, identified as the artist’s grandmother’s, through a pixelated street-view of the Parliament Hill in the background with additional stamps of passage and immigration in the foreground. The stamp in the bottom right hand corner reads April 25, 1967, referencing this woman’s entrance into Canada, and also commenting on the broader changes in Canadian immigration policy around this time period.

Canadian immigration from British colonies, located in what was then referred to as the “Far East”, began in the early twentieth century. Even in the beginning, the settlement of South Asian “others”, particularly the female “others”, was coloured by racial discrimination. In this cultural climate, it was not surprising for the editor of Vancouver Sun to write of the Indians: “They are not assimilable people… We must not permit the men of that race to come in large numbers, and we must not permit their women to come in at all”. The decision to create work centering on the South Asian female body is radical because it gives space to these women and, also, for its elaboration on Canada’s racist history. Aujla’s return to 1967, the year when immigration policies were amended to become more open to South Asian women, transforms this recorded moment into an open gulf where her departure into the past collides with her grandmother’s arrival into this new country.

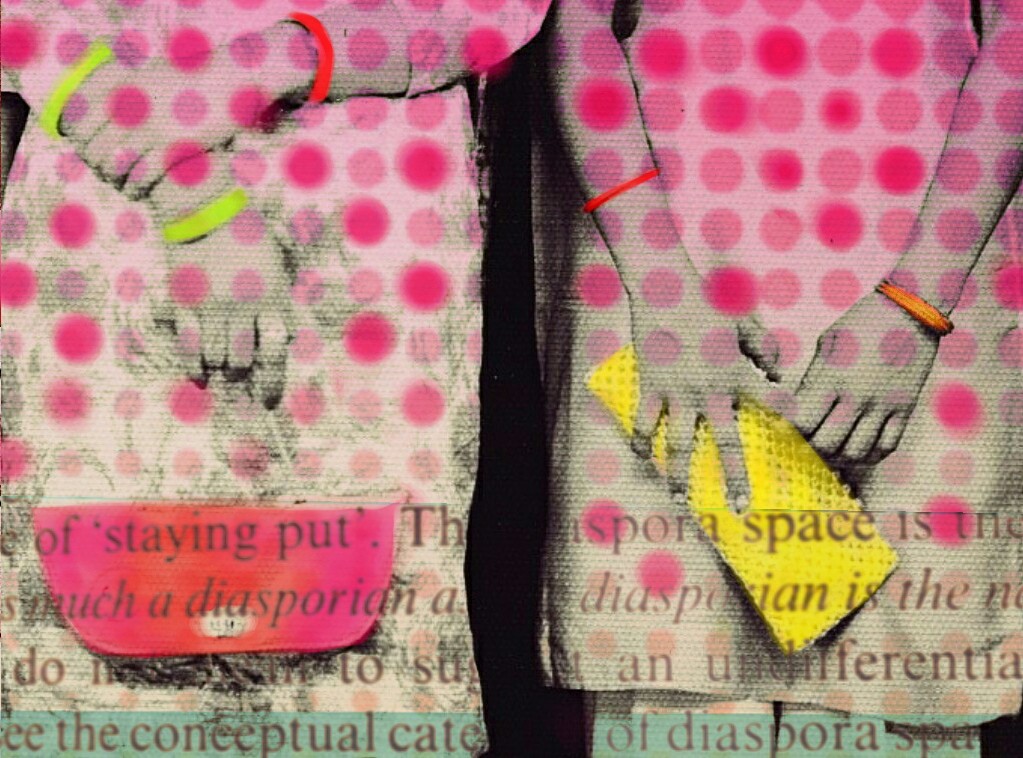

These collisions between the past and the present, here and there, are made productive through the medium of digital collage. In Aujla’s hands, the cut and-paste style reinforces the feelings of brokenness. Her work Pendjabi is particularly rich. A Punjabi is one who belongs to Punjab, an Indian state and my home. The name is formed from two Persian words, “panj” meaning “five” and “ab” meaning “rivers”. Through this formation, Punjab becomes the land of five rivers. In her image, Aujla breaks up this full-bodied word and re-joins “ab” with “pend”, which for immigrants is linked to the endless period of waiting before the gift of immigration or citizenship.

Pendjabi (2016), Angela Aujla, Digital Collage

In the left half of Pendjabi, the double portrait of two women is repeated and stamped with a white stripe declaring their location in the watery depths of waiting. In the right window, Aujla focuses on her grandmother again to halve and colour her in order to exaggerate the broken nature of being an immigrant. In my own reading, Aujla’s mode of splicing through digital collage and creative word formation suggests that we become fractured and put together in unpredictable ways in our movement from nation to diaspora. The method of digital collage helps Aujla connect disparate parts of her history while broadly interrogating the ways in which some bodies are left out of history and made to wait for inclusion.

The point of going back in time to these moments and focussing our gaze on these women is to speak to their specific place in history and allow their agency to emerge through the visual pastiche. Diaspora will always be tricky and we could always be wandering at the borders of nation and history, anxiously waiting for inclusion. Angela Aujla offers us a way out of our despair: we don’t have to wait; we can cut and paste our way into the fold.