Bookmark this: Why we’re fed up of weak excuses from anti-imperialists accepting MBEs

How should we respond when people of colour who've spent a lifetime cussing the empire start curtseying to it instead?

Prishita Maheshwari-Aplin

17 Jun 2021

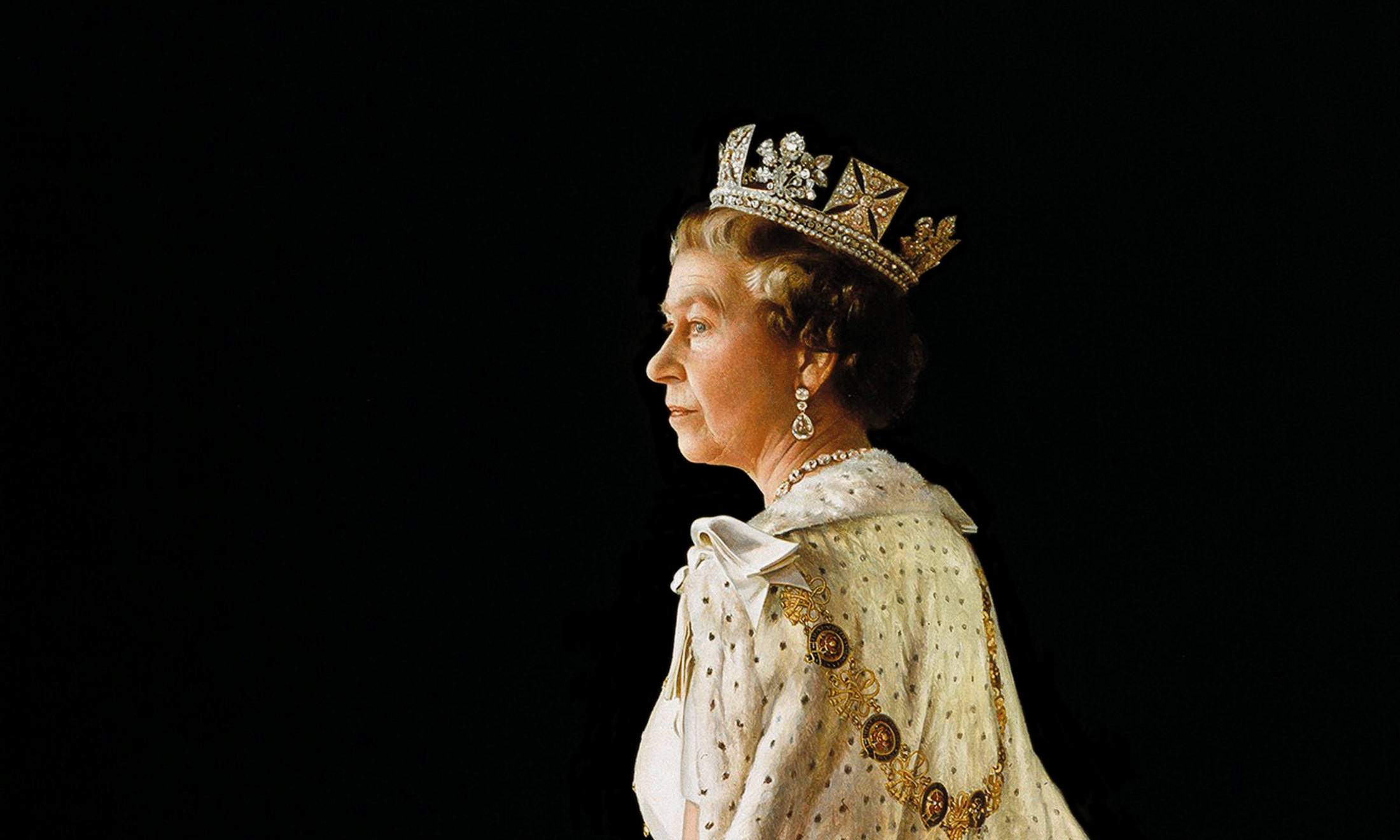

Instagram/Wikimedia Commons

Each year, the release of the Queen’s birthday honours list marks the return of a demoralising discussion around accepting Order of the British Empire awards. This isn’t discourse most of us enter into willingly; instead we’re dragged along, kicking and screaming, by those in our communities who insist on highlighting their sudden disregard for previously-professed principles. Founded by King George V in 1917, the Order of the British Empire represents a time when the empire had violently colonised more than 412 million people and covered a quarter of the world’s land mass. The clue is in the name. Therefore, it’s unsurprising that the decision by some people of colour to receive a shiny new sign-off, forever attaching the word ‘empire’ to their names (the five classes of honours include becoming an Officer (OBE) or a Member (MBE) of the British Empire), raises some eyebrows.

Of course, people of colour don’t automatically represent or hold a great responsibility to change the political landscape for their entire communities. But when those who have made their names from challenging the lingering evils of the empire jump at the chance of being superficially validated by it, the hypocrisy is extremely grating.

From singer Ms Dynamite to author Bernardine Evaristo, musician MIA, and most recently Amika George – founder of the Free Periods campaign – this pattern has been repeated countless times over the past decade. “Is the acceptance of an honour linked to the empire a betrayal of those ancestors and that history?” asked historian David Olusoga in a 2019 Guardian piece written to explain his own acceptance of an OBE. This U-turn by Olusoga, who only three years prior had written Black and British: A Forgotten History, highlighting the impact of colonialism and slavery in particular, stung especially.

“When those who have made their names from challenging the lingering evils of the empire jump at the chance of being superficially validated by it, the hypocrisy is extremely grating”

These individuals will always find a selfless excuse. Olusoga claimed his acceptance was to make a “tiny breach in the wall of racism” by acknowledging Black people’s contribution to British culture – as if a pat on the back by the state for one Black person will erase the long-lasting impacts of Britain’s violent colonial past. The previous year, Ms Dynamite defended her decision to receive a MBE despite “long-held, deep, negative feelings about empire, establishment, colonisation, the suffering it caused and the suffering that continues today”, because she wanted to “honour her Windrush grandparents and their sacrifices”. MIA – whose music has been described as “anti-imperialist” – gave a similar reason, saying she accepted her award “in honour” of her mother.

Bernardine Evaristo announced her 2020 “upgrade” from MBE to OBE by posting on social media that she believed “full participation in this country includes the national gongs, even those with anachronistic titles”. Along with the ridiculous suggestion that the only issue with these awards is the title, the notion that people of colour need to compromise their principles in order to ‘fully participate’ in the state aligns uncomfortably close with historical ideas around integration. It simply isn’t progress to place people of colour within white supremacist environments – and it certainly doesn’t liberate the masses. As for Amika George, she ‘exclusively’ explained in Vogue that she had considered rejecting the MBE, admitting that the word ‘empire’ “conjures horrific images of racist exploitation, economic extraction and a continuing legacy of global division.”

Just a few paragraphs later however, George confessed she’d ultimately decided to accept the (dubious) honour because doing so would “reframe” the MBE and show “the next generation of young British Asians that they hold just as much political power as their white friends”. When Priti Patel is the most powerful woman in the country, surely this demonstrates that political representation of people of colour is not, and never will be, enough to liberate those who have been historically oppressed?

“The notion that people of colour need to compromise their principles in order to ‘fully participate’ in the state aligns uncomfortably close with historical ideas around integration”

“So, perhaps, as a young person of colour, I don’t have the luxury of rejecting this MBE,” George continued. “The opportunity to represent my community and my family, to draw attention to the lack of colonial history in our education system, and highlight the stark underrepresentation of young people in political spaces, is one I can’t let slip by.”

This doesn’t make sense. What does it mean for George to not have the “luxury”, or privilege, of rejecting an MBE? Surely, the alternative would not risk her wellbeing or plunge her into poverty. The bastardisation of intersectionality by neo-liberal feminists has led to the co-opting of terms such as “privilege” to excuse individualism and self-interest. Let’s face it: awards of empire going to individual people of color don’t do anything to change the (racist) status quo. Countless people of colour have accepted the awards over the years, yet the material reality for Black and brown Brits is still one of institutional racism.

Besides, other people of colour have rejected awards of the empire. Poet Benjamin Zephaniah turned down an OBE in 2003 with the words: “It reminds me of slavery, it reminds me of thousands of years of brutality, it reminds me of how my foremothers were raped and my forefathers brutalised.” The awards have also been rejected by the likes of footballer Howard Gayle and more recently, author Nikesh Shukla. White people too have challenged the morality of accepting something so intrinsically linked with the bloody stain of empire; in 2016, former BBC presenter Lynn Faulds Wood refused the offer of an MBE saying: “I would love to have an honour if it didn’t have the word ’empire’ on the end of it. We don’t have an empire, in my opinion”.

“Accepting an award from the literal head of the empire reeks of disingenuity for those who ‘educate’ others on ‘doing better’ when it comes to anti-racism”

Rather than a bold political action, the rejection of an Order of the British Empire award is the bare minimum. Especially for so-called activists who have garnered support by challenging racial injustice on public forums, only to sell out at the first sign of a gold star from the Queen. Accepting an award from the literal head of the empire reeks of disingenuity for those who ‘educate’ others on ‘doing better’ when it comes to anti-racism. It would be far less insulting for honourees to be upfront about their desire for the status that accompany a Queen’s birthday honour, than to claim to be making some great personal sacrifice for the sake of representing their communities.

“Affirmation, acceptance or award from the colonial legacy of the British empire, be it the Queen or colonial-era titles is not validation of hard work,” tweeted ‘Vote Leave’ whistleblower Shahmir Sanni who is someone with first-hand experience of being used by the state to ‘brownwash’ nationalist institutions. “It is a weaponisation of your work in order to twist the branding and identity of that colonial legacy.” Sanni’s words cut through Amika George’s claims that accepting this award will provide her with more opportunity to continue the good work. While the empire requires participation by foot soldiers of colour to rehabilitate its violent image and make it relevant within the modern landscape, the reverse is not true – we must distance ourselves from the idea that people of colour require this validation to be heard.

We need to criticise the systems that teach communities of colour that ‘success’ looks like proximity to whiteness and affirmation by the British state. But we should also seek consistency by those positioned as leaders of movements. Ultimately, the acceptance of an Order of the Empire award is a personal decision – but those whose successful careers are woven into the fabric of anti-racism advocacy must accept that it will be accompanied by a loss of credibility within these spaces.

We can only hope that self-interest and the lure of state recognition doesn’t overwhelm future generations of supposedly anti-imperialist Black and brown creatives, academics, and activists, so much so that they allow themselves to become tools for the empire’s PR machine. But – in the likely circumstances that history will repeat itself for yet another year – bookmark this for the next time one of your faves gives a weak excuse for accepting an MBE.