The End of the Elizabethans: are we ready for a UK republic?

Is it time finally put an end to the long shadow of the Crown?

Kimberly McIntosh

16 Mar 2021

Diyora Shadijanova

On 1 July 1962, Jamaica’s House of Representatives is lively with dialogue. Like many of Britain’s colonies on the eve of independence, Jamaica is using a parliamentary system inherited from the Mother Country – the UK. But on 1 July they have been “betrayed”; the Queen has just given Royal Assent to the Commonwealth Immigrants Bill, making it UK law. It means an end to free movement within the Commonwealth, restricting it for members of the New Commonwealth, namely Black and brown people from majority non-white nations in the West Indies and later South Asia.

After 300 years of allegiance to the Crown, Mr Peart, an MP from the People’s National Party and Second World War veteran, is horrified at this “betrayal” of not only his military service for Britain but also Jamaican loyalty to the Commonwealth in its “darkest hour”. Jamaican Labour Party Member and future prime minister, Edward Seaga, says Britain is no longer fit to head a multiracial Commonwealth. One newspaper asserts that the Queen should not visit Jamaica and some political opinion even pushes for withdrawal from the Commonwealth altogether.

This crisis didn’t dissolve the relationship between Britain and Jamaica, although it did reconfigure it. To this day, Jamaica still has the Queen as its head of state, as do 14 other former colonies and current dependencies including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Barbados, the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda and the Falklands (although Barbados aims to remove the Queen by November 2021). It is also still part of the Commonwealth, the Empire’s younger sibling that’s steeped in the same fraught histories of imperialism, enslavement and the fight for abolition and self-determination. Only two of the 52 members of the Commonwealth are not former British colonies. The Head of the Commonwealth – a symbolic role – is Queen Elizabeth II.

The blockbuster Oprah interview with Prince Harry and Meghan Markle, Duchess of Sussex that aired in the UK on Monday, has made the Commonwealth the talk of the town.

Racism is smelly, and once there was a whiff of suggestion that Harry and Meghan might talk about it, the Commonwealth was used as a post-racial, post-imperial shield against the stench. Speaking to The Times, a “palace source” took umbrage to the suggestion royal household staff resented Meghan’s African American heritage and defended themselves by saying:

“Because of the Queen’s links with the Commonwealth, and her desire to represent all Britons, they have bent over backwards to be inclusive. It is absolutely wrong to say the Palace is institutionally racist.” It is worth noting that there has been a public accusation of racism involving the Palace, where a Black former secretary for Prince Charles alleged racial abuse from white staff.

Meanwhile, Paul Burrell, Princess Diana’s disgraced former butler told TV presenter Lorraine that the Queen is not racist because: “Her Majesty’s greatest achievement is the Commonwealth – she doesn’t see colour.” It is worth noting that during their interview, neither Meghan nor Harry suggested the Queen is racist or had done or said anything racist.

“Racism is smelly, and once there was a whiff of suggestion that Harry and Meghan might talk about it, the Commonwealth was used as a post-racial, post-imperial shield against the stench”

However, they did sketch an unsavoury outline of life in “The Firm”. The pair alleged they were left remarkably unsupported as racist tabloid commentators ripped into Meghan and racist trolls threatened their lives, driving her to consider suicide. Meghan was surprised by the lack of support, specifically citing the nature of the Commonwealth and the pressing need for the royal family to remain relevant to overseas populations. “[It’s] a huge part of the monarchy,” she said, “[About] 60-70% are people of colour.” Meghan couldn’t understand how having her, a biracial duchess, wasn’t seen by the ‘Firm’ as “an added benefit”. It speaks volumes to the blinkered prejudice of other royals that they couldn’t put modernising – and a refreshed claim to relevancy – before their bigotry.

But the Commonwealth isn’t suddenly “a voluntary association of 54 independent and equal countries”. just because that’s how it’s being presented by the Palace. The children of the Mother Country haven’t been elevated to an equal footing with their former coloniser. Last Friday, Kenyan MP John Kiarie said a proposed UK-Kenyan trade deal would “slide [Kenya] back to the colonial period,” due to what lawmakers believe are unfavourable terms. You cannot tell the contemporary story of the Commonwealth without the Empire and exploitation. You cannot understand the history of the Empire without the history of a racist monarchy. Meghan’s mistake was believing this history was consigned to the past.

The monarchy and the Empire

England’s first slave trader was a favourite of one of our most famous monarchs. After several lucrative slave expeditions in the late 16th Century, including a violent capture of 300 Africans in Sierra Leone, Queen Elizabeth I began to sponsor the journeys of Sir John Hawkins. She supplied ships, guns and other materials, as well as a unique coat of arms bearing a bound slave. His three major slavery expeditions in the 1560s prepared the path for the triangular trade of enslaved Africans, raw materials and manufactured goods between England, Africa and the New World. It also signalled a symbiotic relationship between the Crown, enslavement and later the Empire (Sierra Leone would formally become a British colony in 1808).

By 17th century, King Charles II and his brother James, Duke of York, helped establish The Royal African Company (RAC) of England, whose Latin motto translates to: “by royal patronage commerce flourishes, by commerce the realm.” The company, which had a monopoly over the English slave trade until the early 18th century, sold enslaved Africans that were branded with the initials ‘DY’, standing for Duke of York, the company’s largest shareholder. This period coincided with the colonisation of the Caribbean, and a burgeoning “scientific”philosophy of races that justified the enslavement of Africans, and later imperial expansion. During this time, the Barbados Slave Codes were passed: racist laws that legalised slavery, described Africans as ‘a dangerous kind of people’ and allowed the most violent punishments for supposed “deviance”.

Fast-forward to 1799 and the campaign for the abolition of the slave trade is gaining momentum. But Prince William, the Duke of Clarence (and the future King William IV), gave an impassioned and widely circulated speech in the House of Lords defending the slave trade. His efforts helped ensure the abolition movement failed between 1780s and 1790s. Prince William Frederick, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh, was an anti-slavery campaigner, but an exceptional case.

The rapid expansion of the British Empire in the 19th Century was also closely associated with the monarchy, most famously with Queen Victoria. During her reign, she became the symbol of the British Empire and was a strong supporter of Britain’s imperial ‘duty’ to spread “civilisation” to the “darkest corners” of the globe. In 1877, she assumed the title of Empress of India. “The idea of ‘civilising’ the people they ruled was very important to the Victorians,” Sarah Richardson, professor of history at the University of Warwick, told History Extra magazine.

This may seem distant history to some. But in the interview, Harry recalls a conversation with a member of the Royal Family who expressed concern about how dark their son Archie might turn out when he was born. Racism within the monarchy runs deep because their position depends upon it. When the Princess Michael of Kent wore a Blackamoor brooch to her first Christmas lunch with Meghan Markle and claimed she meant “no malice”, it was more of the same.

Prince William told reporters on Thursday that “[the royals] are very much not a racist family”. But a dynasty that is built on the premise that some are born to rule, and Black and brown people are to be subjugated, cannot be truly modernised. But is there yet the public sentiment necessary to remove it altogether? And if not – why?

The British Republic?

“Face to face with globalisation, the internationalisation of music, art… people still want to know – am I rooted anywhere? Am I rooted in anything?”, the late cultural theorist Stuart Hall told Radio 4 listeners in 2011. “The question is: how do you find somewhere to stand and do you imagine this will be the same as it used to be?”

This is a question we are still in the process of answering. Keir Starmer’s Labour party is plagued by it. The Tory-driven culture wars seek to imagine it’s “the same as it used to be.” Brexit was in part driven by it. The Royal Family chose the past over the patina of progress and the sheen of modernity that, for minimal effort and materially little threat to the status quo, could have been theirs. All they had to do was accept Meghan, a racially ambiguous, biracial African American actress, into the family. Her children – with their “threat” of “dark skin” and “exotic DNA” – would never be in danger of ascending the throne.

“In 1997, a televised debate titled The Monarchy – The Nation Decides aired, with Trevor McDonald hosting. The queen reportedly tuned in after her dinner”

Has the royal rejection of Meghan heightened republican tendencies among generations? Good question. It’s not like we’ve not been here before. From Edward VIII’s abdication to Princess Diana’s ostracisation, the 20th century was littered with royal crises that ostensibly threatened the future of the monarchy. In 1997 (prior to Diana’s death), a televised debate titled The Monarchy – The Nation Decides aired, with Trevor McDonald hosting. The queen reportedly tuned in after her dinner and the final result was 66% in favour of preserving the royals.

Flash forward to 2021 and in a YouGov snap poll, nearly half of 18 and 24 year-olds feel more sympathy for Harry and Meghan, with only 15% more sympathetic to the senior royals. Britons aged 25 to 49 years-old are split 28% for team H&M to 24% for the senior royals. The future of the royal family lies here, and for these generations, the majority either back Harry & Meghan or don’t know. This, it’s worth noting, comes after allegations that Prince Andrew raped a teenage girl and recent reports in The Guardian that the Queen politically interfered to hide her “embarrassing” private wealth from the public.

The royal family is arguably experiencing its darkest hour since Diana’s 1995 interview with Martin Bashir – but this time there’s no tragic event for them to rally round. However, there is a next generation of royals waiting to take up the crumbling mantle helmed by Prince William, who is bafflingly the most “popular” member of the family.

Frankly, it is unlikely that we will see the demand for a republic become mainstream political discourse anytime soon. But that is exactly why we should push for it; Brexit was once a pipe dream of a few cranks on the right and now it’s the defining political event of our generation. The argument for throwing out the royals can appeal to left and right but for us, we need to focus on how the continued presence of the decaying dynasty is poisoning the entire well.

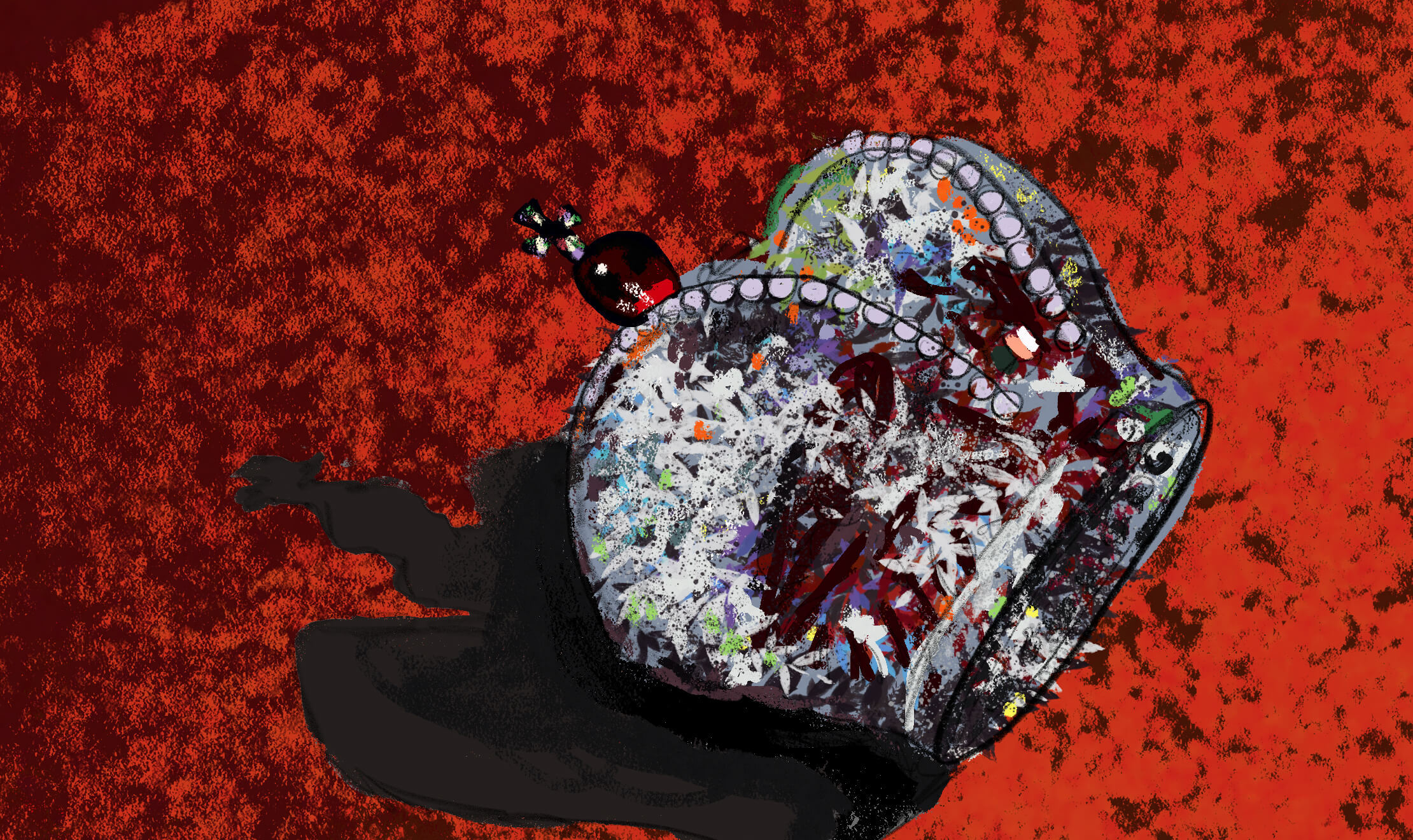

The Windsors are the ultimate emblem of elitism, mediocrity, unearned wealth, privilege and power, as well as being a physical reminder of the brutality of colonialism. As long as they persist, we cannot move forward; they are a bejewelled albatross around Britain’s necks, dragging us into a past that no longer exists. Finally ridding ourselves of the monarchy would spark real questions around what sort of state Britain wants to be and how we build that.

Symbols matter. By dint of existing the royal family says the quiet part loudly: know your place, suffer silently and be grateful.

We’re capable of moving forward, to remake definitions of glory and greatness. We can turn palaces into museums as has been done at the Palace of Versailles in France and the Winter Palace in Russia. The Commonwealth could have an elected head of state, if it must continue to exist. Maybe even a leader from a developing country that isn’t white.

For Britain to become a functioning democracy would take more than ending the line at Elizabeth II. But we should start here.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?