What are we missing in the fight against Islamophobia? Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan gets to the point

A new book by Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan looks beyond entrenched narratives of Islamophobia to offer a new thesis.

Mariyah Zaman

28 Mar 2022

Pluto Press

‘Great,’ I thought wearily, upon hearing about the upcoming publication of Tangled in Terror: Uprooting Islamophobia. ‘Another book on Islamophobia that likely dances around the semantics and doesn’t really do much to amplify the voices of Muslims.’

Over Zoom, I put this to the book’s author, writer and poet Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan, and we both laughed at my misjudgment of the work (by its literal cover). To quote the opening chapter, Tangled in Terror isn’t interested in definitions of Islamophobia or proving its existence (the world does that for us), but instead asks questions about its impact, and argues that “the only way Islamophobia can be uprooted is by sowing the seeds for another world altogether.”

At 170 pages, it’s a short but punchy work. Within, Manzoor-Khan manages to articulate the complexities of race, security, counter-extremism, secularism and violence concisely and in an accessible manner, without compromising her values as a Muslim. On a personal level as a Muslim woman, I finished the book, equipped with the ability to put words to micro-aggressions of Islamophobia I have experienced in my life, whilst also being able to better understand the insidiuous ways Islamophobia manifests in British society.

Born in Bradford, Manzoor-Khan achieved renown after her 2017 spoken-word poetry performances at the National Roundhouse Poetry Slam in 2017. Born to second-generation British-Pakistani parents, Manzoor-Khan’s thesis at university focused on how Muslims and Pakistanis are targets of the British surveillance state.

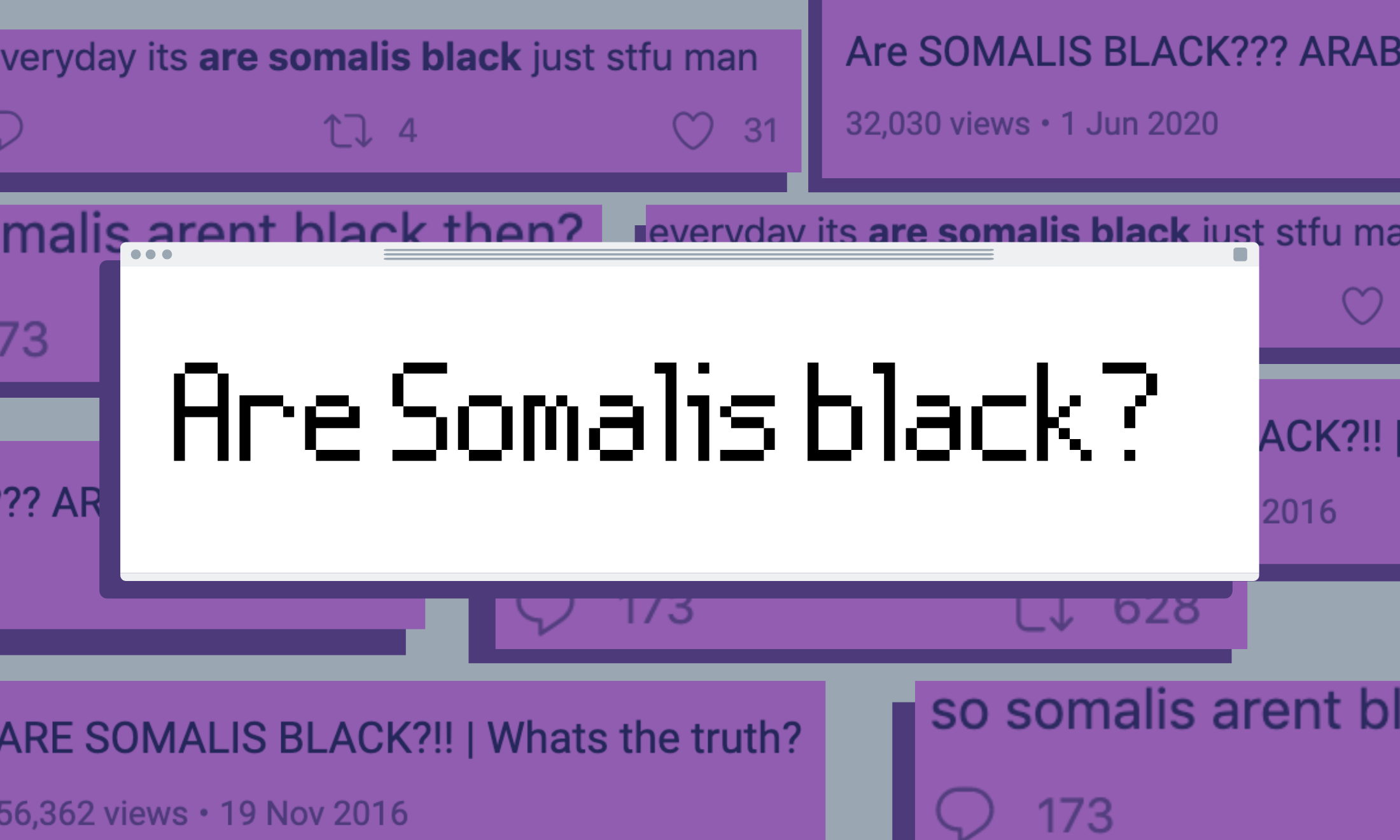

In her book, Manzoor-Khan acknowledges her positioning as a Muslim of Pakistani heritage which she admits may leave her to blind spots and particular erasure of the intersection of anti-Black and Islamophobic narratives. She makes it clear that Islamophobia cannot be uprooted without uprooting all forms of racism, providing a fresh perspective that breaks away from the over-representation of South-Asian Muslims in the conversation on Islamophobia.

Normally, I shy away from reading books on issues that are so closely related to my own identity, simply because so many get it wrong. But Manzoor-Khan didn’t. So gal-dem reached out for a chat about how she changed the record on the way we think about Islamophobia.

gal-dem: How do you feel this text is different from most texts that address Islamophobia?

Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan: When I was approached to write this in the first place, I was like okay; the conversations that I’ve seen around Islamophobia are either around defining it, or are just really academic. They’re not very accessible.

I would like to think that what makes this book stand out is that it’s more concerned with placing Islamophobia within a broader history and structure of racism in general and I think that to me is what is often lacking in our analyses.

This book is trying to say Islamophobia is a manifestation of something that has much deeper root causes and that those root causes are a world system. It’s not something that’s unique to Islamophobia. It’s colonialism, it’s racism, it’s white supremacy and all of that is linked to capitalism and all sorts of other oppression.

You mentioned that you were approached to write this book…

This book is part of Pluto Press’ Outspoken Series where they deliberately pick out authors who are activists in some way, or can speak to a broader audience as opposed to just academia. The series covers topics such as work, masculinity, feminism, borders, global warming etc and they always come from an angle of how we resist these things and radically conceptualise them.

If you weren’t approached, would you have written a book about Islamophobia?

I don’t think I would have, if I’m really honest. Firstly because, who is going to be interested in publishing that? It seems to me that the books that are published about Islamophobia tend to uplift a narrative that I feel often puts the onus on Muslims to do more to disprove certain myths. So firstly, I don’t know where it would have been published, and secondly, sometimes you just need someone to give you the idea.

In the book, you address how secularism invented the category of what we understand to be religion and what ‘counts’ as religious life. You mention the effect this has had on young Muslims you have worked with that have internalised the negative attitudes pitted against them. Why do you think that we don’t naturally interrogate the secular definition of what religion is today?

That’s a hard question, because when something becomes known to you it’s always hard to track back as to why you didn’t know before. Secularism isn’t pitched as a one alternative in a world of many different ways of thinking. It’s just pitched as the ‘best’, the ‘most neutral’, the ‘most modern’, the ‘most democratic’, ‘most egalitarian’ structuring of society.

Something that I wanted to explore in the book was how much our own understandings of Islam have actually been co-opted, where the discussions internally are now being centred around questions of “Is it legitimate to be violent? What are the rights of women?” That’s not to say these are questions that should not be asked, but it’s the fact that we are asking these questions on the terms of a non-Islamic world view that perceives Islam to already be ‘guilty.’ Thinking about myself growing up as a young Muslim, you don’t really get a chance to go and explore Islam on its own terms.

Throughout the book, you use inverted commas around the words ‘terrorist’ or ‘terrorism’. Why is that?

I think when we use the terms ‘terrorism’ and ‘terrorist’, we’re basically accepting that a ‘terrorist’ is a type of person and that ‘terrorism’ is a type of violence. If we unquestionably accept that, we already concede to a narrative in which non-state perpetrating acts of violence are seen as exceptional with an innate tendency to be violent.

I wanted to put quotes around it because when you put quotes around something you reinforce the fact that something is named, it is a label. It is not a natural thing. So when you do something like that with terrorism, it helps to question, “actually, what type of violence is not terrifying?’ A big question asked throughout the book is simply, what is violence? What does safety actually look like?”

There could likely be a backlash with all the people and think-tanks such as Micheal Gove and the Henry Jackson Society that you have named and shamed in the book for perpetuating Islamophobia. It has probably taken a lot of delving into trauma to write this. How do you navigate that?

I’ll be really honest, this is where being a Muslim is really the greatest asset in terms of perseverance. From the perspective of a Muslim, our protection comes from our creator. So as a Muslim you are as safe or unsafe as your creator decides for you to be. Islamically, it is incumbent upon us to speak out against injustice. I think writing a book like this is also a responsibility. The way I see it is that you have to either go hard or go home.

We all deal with trauma in different ways and I think for me, this feels like a purposeful use of those experiences in being able to say inshAllah, here is a tool, something others can benefit from, or even myself on a basic level to analyse those experiences and say ‘ohhh, this is why that happened.’ It makes it less personal and frightening.

Tangled In Terror: Uprooting Islamophobia is out now, via Pluto Press.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?