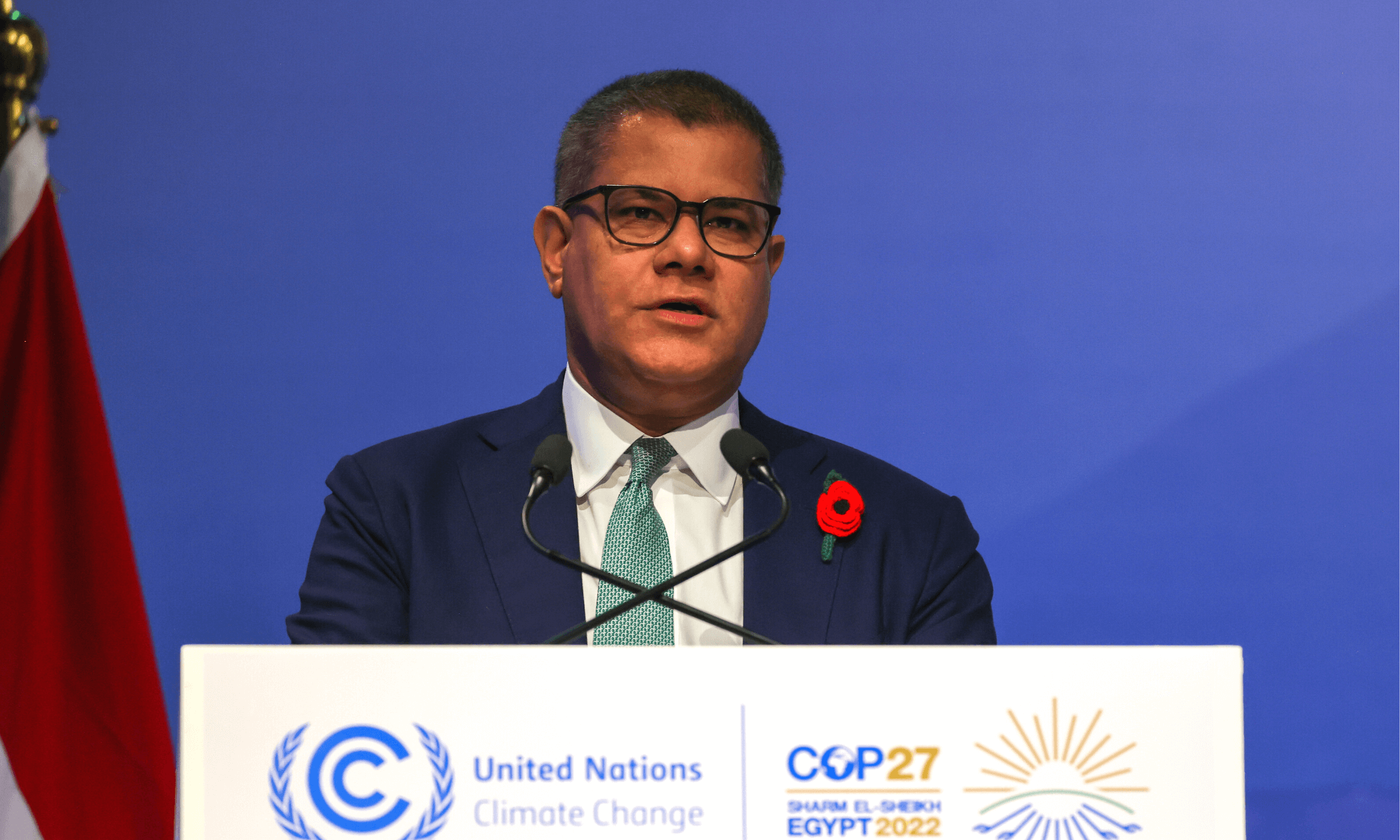

Rory Arnold / No 10 Downing Street

Err, so what just happened at COP27?

A big win for Loss and Damage and a colossal disappointment for everything else.

DiyoraShadijanova and Editors

23 Nov 2022

The annual United Nations Climate Change Conference – also known as COP – is never as straightforward as you think it’d be. Surely, as the UN Secretary-General António Guterres makes a stern warning that humanity is “on the highway to climate hell with our foot still on the accelerator”, global leaders who have specifically gathered to solve the climate crisis would be desperate to enact policy that tries to save us all from extinction? Right?? Unfortunately, after nearly 30 years of these climate conferences and no tangible progress, even this seems too much to ask.

Despite numerous climate coalition groups pushing for radical action to stop the world from burning, fossil fuel lobbies have resisted the hardest. This year, a shocking 636 fossil fuel lobbyists gathered in Egypt, where the conference was held – forming the second-largest delegation after the United Arab Emirates. This is a 25% increase from last year’s COP in Glasgow.

So it’s no surprise that at the end of the two weeks in Sharm el-Sheikh, COP27 is largely being considered a failure. Despite the win for the Loss and Damage fund, everything else looks bleak against the backdrop of a rapidly warming and increasingly polluted planet.

ICYMI, these are gal-dem’s key takeaways from this year’s COP27 conference:

A win for Loss and Damage

COP27 saw through a historic ‘Loss and Damage’ deal, which is the first step to recognising that rich countries should provide money for vulnerable countries to deal with the disproportionate impacts of the climate crisis. It’s a breakthrough development and a win for all the pressure groups and campaigners calling for a Loss and Damage fund.

Friends of the Earth’s international climate campaigner, Rachel Kennerley, said: “The welcome decision to create a loss and damage fund was the only just outcome of COP27. This is an important step forward in re-addressing the balance between those that have done the most to cause climate change and those least responsible but who suffer the worst impacts.”

Still, the agreement could have been better – without a commitment to limiting global temperatures and phasing out fossil fuels, a Loss and Damage fund will only deal with the symptoms of the climate crisis, not the cause. And though more than 190 countries agreed to establish a fund, it’s unclear how much money the fund will need, who will pay in and who is eligible for compensation. Since rich countries have already failed to provide $100bn a year in financing climate-related projects in developing countries, questions arise about how tenable this policy is.

Keeping 1.5C alive (just), with no commitment to phasing out fossil fuels

Last year at COP26, countries agreed to focus on limiting global heating to 1.5C, but commitments were incompatible with this ambitious number on paper – despite countries’ climate pledges, the world was on its way to 2.4C warming. Negotiators agreed that COP27 would be a chance to revisit and strengthen commitments. In Egypt, not only did some countries try to go back on their promises of 1.5C, they also took out the resolution for emissions to peak in 2025.

Global leaders know that any fossil fuel expansion will make limiting warming to under 1.5C almost impossible. However, at COP27, talks to phase out all fossil fuels failed, with countries doing very little to strengthen the commitments they made during COP26. As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the global energy crisis dominated negotiations, oil and gas-rich countries undermined negotiations and watered down commitments. In the final text, negotiators added a provision to boost “low-emission and renewable energy”, which critics worry is just a nod to natural gas as it is considered cleaner than oil and coal, but still is very much a fossil fuel.

A mention of tipping points with no action points

The COP27 decision text mentioned tipping points and “nature-based solutions” for the first time, explaining that the climate crisis will be self-sustaining and irreversible if tipping points – such as the collapse of the Antarctic ice sheet, permafrost collapse or Amazon dieback – are triggered. Though the negotiating countries have now formally recognised tipping points, there have been no significant policy actions to avoid them.

A resounding failure, but not a reason to give up

Everything else feels like hot air without a serious commitment to reducing emissions. And as it stands, current commitments will make us reach 1.5C in the next five to 10 years, which will be disastrous for the most vulnerable countries in the world. A recent report shows that the world is on track to produce double the amount of emissions in 2030 than it should to meet the 1.5C target. The COP27 conference did not address the widening gap between climate science and policy.

Still, it’s never too late to hope and push for radical climate justice, because giving up now is the worst thing we could possibly do. Everything is worth fighting for – whether in conference rooms or on the streets.

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.