‘Most of them come to see me because of their racial fetish’ – why being a sex worker can be very lonely

Wild Iris

04 Jul 2019

Illustration by Hannah Buckman

TW: This article contains description of rape

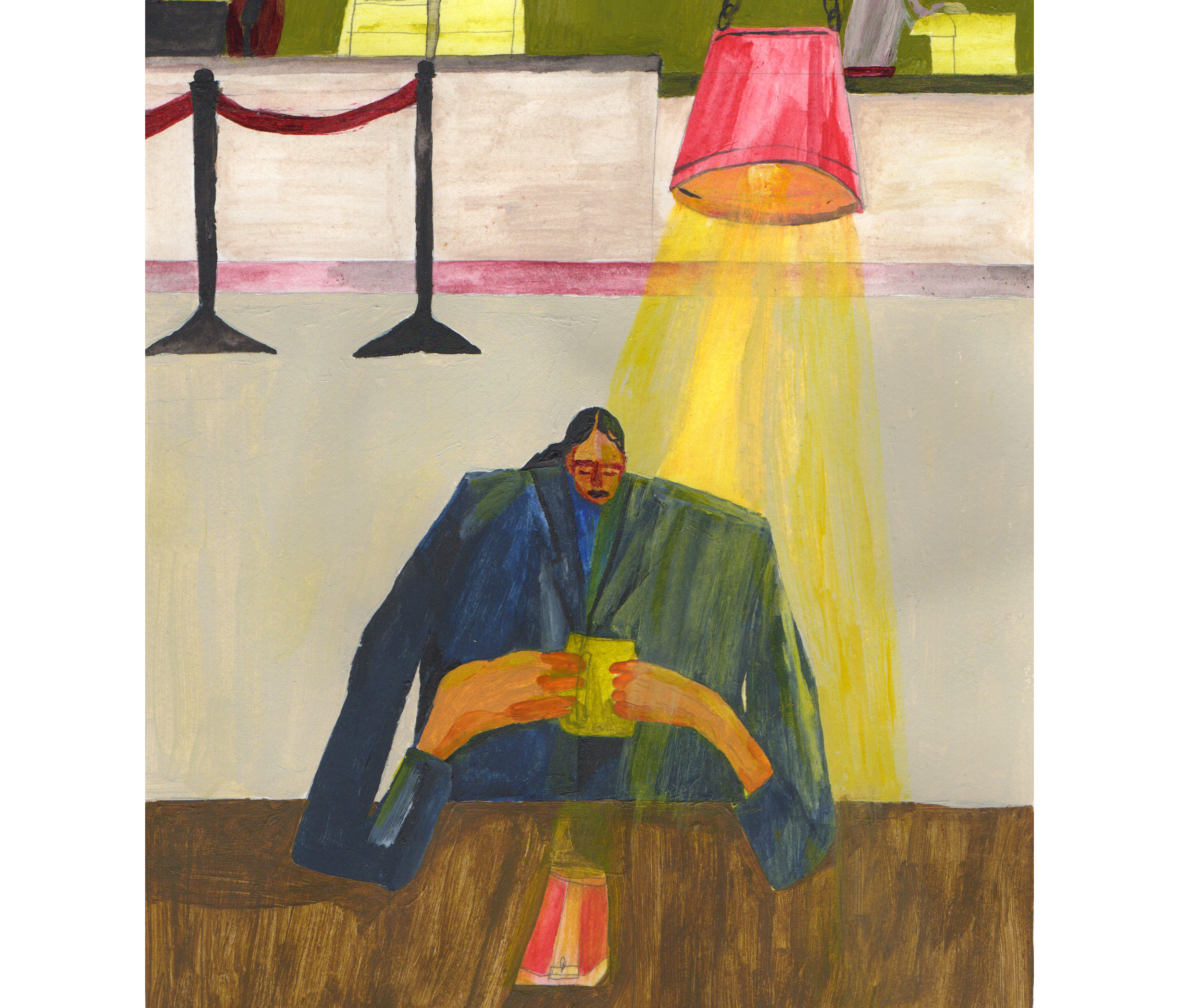

My job is lonely because I have to pretend to be a woman, and being a woman is lonely. In my job, I transform from being simultaneously Unseeable and Seen, to another kind of Seeable and Unseen.

Usually I am androgynous, my overhanging brown folds delineating me into a question mark in the mirror. Outside, I am the kind of UnWoman people are too frightened to fully look at but also can’t get enough of. But at home, I am simply with myself in the mirror. My job then begins at the feet: stockings, then heels, lingerie, makeup, and a few extras. Each item puts a seal of air between me and body, until by the time I am fully dressed, I am the kind of woman people want to look at, an Acceptably Seeable Woman, but also completely hidden, and completely separated from myself – Unseen and alone.

My job is lonely because I have to extend this performance of simultaneously Seeable and Unseen onto every inch of myself. I spend hours online each week, marketing my persona as spontaneous, genuine and friendly. I answer the phone in my most impeccable white people voice. I open the door, I smile, I guide, I caress, I perform, I play all the right parts on my commissioned stage, of friend, therapist, and mother. I am seen so convincingly in these roles that when the praise gets heaped on me for being so genuine I have to stop myself from internalising it too far. I am looked at and touched so much in my actorship that no one sees me, no one touches me. I disappear.

This loneliness is exacerbated by my brownness. I sell “myself” as a brown woman. Clients may not say so but I know that most of them come to see because of their fetish for my brownness and its associated characteristics of hairiness, submissiveness, and animalism. Recently, a white client spent a long time admiring my brown body. He looked me in the eyes with a desire I will never forget, simultaneously piercing me as his little coloured subject, and also rendering me opaque, non-existent.

“White anti sex work feminists see women of colour sex workers as dirty and aberrant”

When he suddenly started to rape me, I felt myself being overcome, not by the injustice of it, but by the loneliness of it. Of being UnSeen until I become an UnPerson like this. When you are an UnPerson, life is lonely because you are not human enough to connect to anybody else. I felt myself being thrown into a crevasse. Usually, I don’t associate work with sexual pleasure. The sex I have at work is completely different to how I conceive of sex in my personal life. This boundary is sacred to me, it keeps me mine. But I was so lonely from being touched all day and never being touched at all, that I broke the film of surface tension established between worker and client, between good victim and bad victim. I let myself enjoy what was happening to me, because at least someone was touching me.

My job is lonely because whatever I say will not be heard. For anti sex work feminists, if I express positivity about my job, I am a sex-positive liberal privileged person who has no right to talk about it (I am certainly not the first two things.) If I express negativity about my job, I am a “prostituted woman” who needs to be saved by abolition, or the Nordic Model. This is especially so as a brown woman.

White anti sex work feminists see woman of colour sex workers as dirty and aberrant, in need of being tamed – doubly so when their carceral, “anti-trafficking” feminist politics coincide with forcible deportations of migrant women. Simultaneously, they see us as voiceless and slightly stupid, their colonial project to be saved by notions of what is good sex and good work. Whatever actual complex thoughts I have about my own means of getting my resources in the world are irrelevant, because ultimately, in a very basic expression of misogyny, I am marked by the amount of sex I have and not by the whole person I am.

So my job is lonely because when I am not seen or heard, I cease to exist. Juno Mac and Molly Smith write about the origins of the word “prostitute” as connected to “putrid”. The prostitute’s body is historically considered to be a site of, but also a drain for, putridity. Clients, then, are not the only ones who extract from and deposit into my body at will. Anti sex worker sentiment, or whorephobia, comes from supposed feminists too, and revolves around making my brown sex worker body into a symbol of meaning, rather than seeing or hearing me as a person. In being spoken of as “prostituted”, I am already spoken out of existence, into the past tense.

These attitudes, supposedly designed to help me, alienate me further. I cannot tell people about my job, and people who know do not ask me how work is anymore. I think they might be frightened to reconcile the image of the putrid drain with the person they love. I notice people who do know touch me less. So I do not speak, to either the people I love or to professionals, about the good things, the bad things, the white man who raped me. I do not get support from therapists, the police, and healthcare. I cease to exist in material reality as a sex worker and become a husk in the shadows of people’s mouths and minds. I become simply a symbolic hole, a drain, an UnPerson.

“Two sex workers sharing a space together can be prosecuted as brothel work – this is lauded as an attempt to protect us, but is really about separating us from each other”

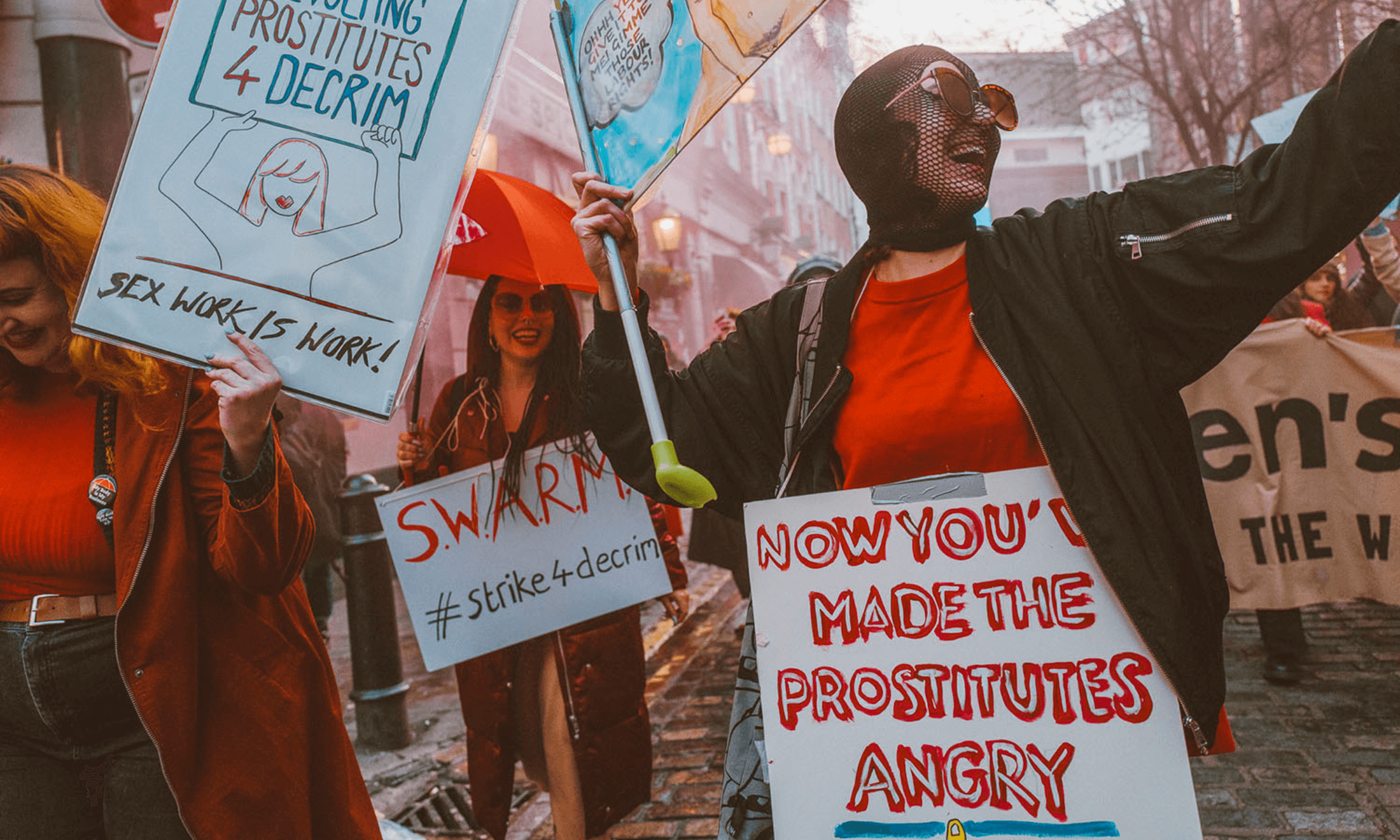

My job is lonely because whorephobia writes my loneliness into the law. When an UnPerson is disappeared by forcibly speaking over them, it is easy to create laws and structures that hurt them further. Despite sex workers’ cries for full decriminalisation of the sex industry so that we might work safely and legally, no matter our opinions on how we feel about the work itself, anti sex work feminists and the law work together to criminalise us, which further harms us. Under Britain’s laws of partial decriminalisation, working in brothels is illegal. However, any two sex workers working or even sharing a space together can be prosecuted as brothel work, even if they never cross paths within the space. This is lauded as an attempt to protect us, especially by proponents of the Nordic Model, but is really about separating us from each other into the dark.

Because of these brothel laws, I work alone, which made it ostensibly easier for that white man to rape me. I would have liked to have someone else in the next room for my safety, and simply to share a cup of tea with afterwards, but I knew that clients often use brothel laws against us. In the end, he did exactly that, emphasising to me that he knew the flat we were in had been used by another worker. I can now never report him without risking being arrested myself, which is exactly what happened to the two migrant workers recently jailed in Kildare. I was lonely when I got ready for that job, I was lonely during, and the law makes me lonely after.

My community comes from other sex workers, and my close friends who still ask me how work is going, who hold me as a person in my complexity rather than a blank symbol to stuff meaning into. Whorephobia towards sex workers, from clients, anti sex work feminists, and institutions, has far reaching ramifications of structural and chronic loneliness for sex workers, beyond what those who UnSee us can have the humility to dream of.