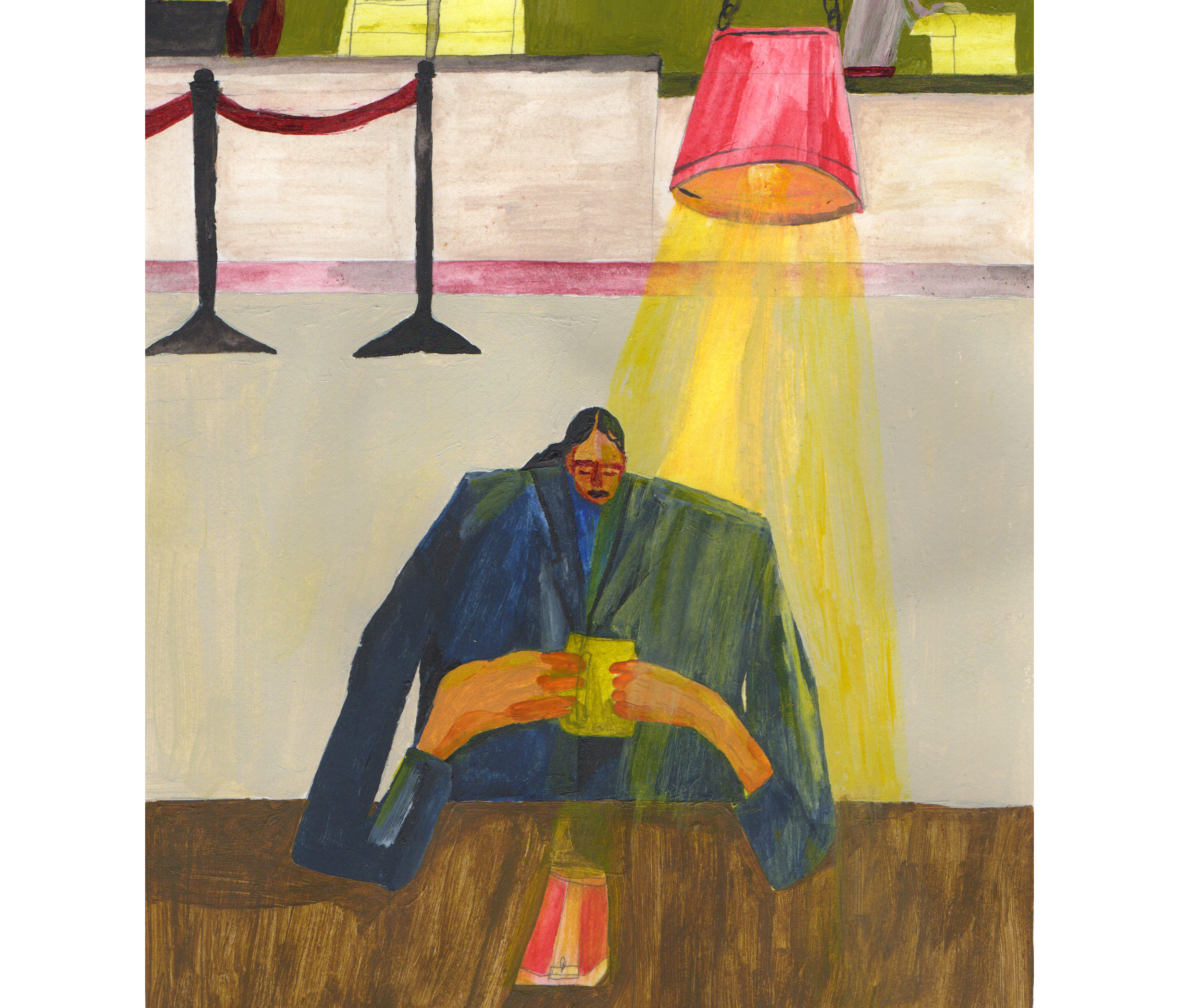

Tessie Orange-Turner

Why Black people in the UK are more likely to be lonely

One in three Black people in Britain report feeling lonely. What's going on and what steps can be taken to fix this?

Lakeisha Goedluck

20 Sep 2022

In the summer, Sheila Seleoane was discovered in her flat – two and a half years after she’d died. Her cause of death couldn’t be determined, her bills were left unpaid and her neighbours consistently reported a strange smell emanating from her home, yet the authorities failed to check on her. Only after one tenant signaled that there was storm damage done to Sheila’s balcony did they find her body – as if the state of the building was more important than her well-being. Sheila was a medical secretary, she was 61 years old, and she was a Black woman. Her story is not only tragic but illustrates alarming statistics that people like her are most likely to experience loneliness in the UK.

In May, the Mental Health Foundation released a report that stated one in three Black people experience feelings of loneliness. By comparison, one in four of the general population reported feeling lonely some or all of the time. After Seleoane was found it became clear that she had no close friends or family. Issues like racism and financial inequality are contributing factors to these worrying stats according to the aforementioned report and also Labour MP Rachel Reeves who went on to conduct her own research. “There are so many different barriers that face different ethnic minority groups in different ways,” Reeves explains to gal-dem. “We know those barriers can make health and social problems worse. We knew that already about loneliness, but the pandemic really exposed it further”.

The Campaign to End Loneliness is a public initiative working to alleviate the problem. In accordance with Reeves’ musings, the campaign published a report titled “Loneliness beyond COVID-19” in July last year, which outlined why Black people have felt increasingly lonely due to the pandemic. The report states that those from ethnic minorities were more likely to be on lower incomes and find it difficult to manage financially pre-pandemic, which the report highlights as “key risk factors for loneliness”. The UCL COVID-19 Social Study, which the report references, explains that Black people and those of Bangladeshi or Pakistani heritage were more likely to see their financial situations worsen as a result of the pandemic. It’s worth revisiting as we head into what many are predicting to be a challenging winter with the cost of living concerns and energy crisis fears looming. Winter months can already be isolating with colder weather and shorter days making it even more challenging to connect with others and adding additional roadblocks to socialising.

This is not the first time campaigners have sounded alarm bells about Britain becoming a country of lonely souls. Alongside fellow MP Seema Kennedy, Reeves has diligently continued the work of the Loneliness Commission founded by Jo Cox MP, who was assassinated in 2016. Cox set up the cross-party initiative, which she intended to run for one year, to tackle the rising cases of loneliness across the country. In 2017, Reeves and Kennedy brought 13 different organisations together and interviewed people from various factions of society on the subject to compile a lengthy report on the crisis. As a result of this work, former Prime Minister Theresa May outlined a governmental strategy for tackling the issue and appointed the first Minister for Loneliness in 2018. This role has been filled by four different MPs in four years and the proportion of adults saying they feel lonely in 2022 remains at 6% –– the same figure reported annually since 2017, suggesting the government’s actions have had little to no effect on the situation.

Obviously, the isolating nature of the last few years has had additional challenges. The report found that COVID-19 mortality rates disproportionately affected those of Black and South Asian heritage –– leaving surviving family members grappling with feelings of loss while, in some cases, newly living alone. Perhaps most disappointingly, the UCL study also found that 42% of people from ethnic minorities experienced discrimination during the pandemic, compared to 24% of white people.

“The racial upheaval and injustice, as well as not being able to see family members or go out during [the pandemic] definitely worsened the feeling of loneliness”, says Ngozi Cadmus, a mental health therapist and leadership expert who founded her own practice, Frontline Therapist, specifically to cater to minority patients. “The reality is, that when our people need help, it doesn’t exist. We need to be more acquainted with what to do when things go wrong.”

Due to lockdown restrictions, social connectivity outside a person’s household was nigh impossible. Those living in London during the pandemic may recall that green spaces were partially or completely closed to allegedly prevent COVID-19 transmission. As The Guardian reported in 2020, these measures predominantly affected those from poorer and BAME backgrounds. This is because a third of all land in the wealthiest 10% of London wards is taken up by private gardens, while in the poorest 10%, just over a fifth is taken up by garden space.

“There are issues that cannot solely be blamed on the pandemic. Our country was already on a path to erasing community spaces.”

But there are issues that cannot solely be blamed on the pandemic. Our country was already on a path to erasing community spaces. Our infrastructure has slowly been built in order to exacerbate loneliness. A protocol called Secured by Design, which was founded during Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s reign, grants the police governance over the design of public spaces –– meaning they can implement changes like the removal of benches and pathways as a means to tackle crime, supposedly. “Judging whether the benefits of an interconnected neighbourhood in which residents can meet one another, get around easily and build positive relationships outweigh the risk of a random burglary should be straightforward,” argues Phineas Harper, who wrote at length on the subject for The Guardian back in May.

In April, the government stopped a review of the right to roam in the English countryside, preventing the public from accessing 92% of the country’s privately owned land. In July, the charity Fields in Trust found that nearly 2.8 million people live more than a 10-minute walk from a public garden, park, or playing field. Fewer places to congregate means a decrease in social interactivity –– especially for the aforementioned groups. Then think about the disappearance of community centres and the closure of libraries and pubs. “English local authorities suffered an average cut of 35% to Cultural and Related Services spending over the period from 2010 to 2017”, says Habib Kadiri, the research and policy manager at StopWatch UK –– an organisation campaigning for fair and accountable policing. It paints a picture where Britain is running out of buildings to welcome people and where the outdoors is also off limits.

A prime example of this happened back in May when Westminster Council tried to bar pensioner Ernest Theophile and his group of friends from publicly playing dominoes in Maida Hill Market Square –– a popular game in the Caribbean, which is where Theophile’s family hails from. After complaints from local residents that the retirees were playing too loudly, Theophile was threatened with jail time; he took the case to court claiming that his racial equality rights were being ignored and won. “He says that access to the square is part of his community ties, where backgammon and dominoes are played and where informal support is given for those experiencing social isolation and issues with their mental health,” Judge Baucher said, who presided over his case.

To worsen the matter, Black people are also inordinately targeted by the police when congregating in said spaces. In 2021, there were 7.5 stop and searches for every 1,000 white people, compared with 52.6 for every 1,000 Black people. “The threat of being surveilled, judged, and accosted for simply existing in public is a constant worry for so many Black people”, says Kadiri. “This is driven by racist stereotypes of Black people’s behaviour which manifest as police ‘self-generating’ searches and acting overzealously on tip-offs by members of the public threatened by the presence of Black bodies in their midst”.

“As a woman of colour, it made me feel like no one was concerned or understood the hardships I was facing because my feelings and experiences weren’t a priority.”

As a Black person, the callousness of the state can exacerbate feelings of loneliness, which is what 27-year-old Karen François endured back in 2020. Originally from Miami, Florida, François moved to London with hopes of joining the creative scene. She was assaulted in her first month living in the city. François says to gal-dem that the way her assault was treated left her feeling lonely. “The police spent months holding my case and never once interviewed any of the witnesses and didn’t begin the investigation until months later when I filed a complaint”, François explains to gal-dem. “As a woman of colour, it made me feel like there was nowhere I could turn to for support in the city. It felt like no one was concerned or understood the hardships I was facing because my feelings and experiences weren’t a priority”. Hesitant to go out with anyone she didn’t know, François initially further isolated herself but eventually found solace by joining online groups.

Various organisations have sprung up to encourage community-based activities for Black people to combat loneliness. Lynne runs the Black Girl Sewing Circle in South London, which provides Black women with a safe space to bond over a shared creative hobby. “Being an African woman, whenever there’s a cultural event like a wedding, you’d usually go to a tailor [for an outfit], but it was just easier for me to make it myself,” Lynne tells gal-dem. “I would get people asking me to make stuff but I wanted to empower people to make their own [pieces] without going to a workshop that wasn’t culturally relevant, as Black people are usually the minority in those spaces”.

Lynne initially found it difficult to secure a space for her workshops but now has a regular spot at Peckham Levels. She says that a lot of the women who attend are highly experienced: “but they’re not coming to learn –– they’re coming to meet other Black women who are into the same things as them, and that’s really nice”. Lynne feels that several community-building initiatives like hers have cropped up for Black women recently but says, “I don’t see a lot for Black men” –– suggesting that there may be gendered issues when it comes to loneliness too.

While the drawbacks of social media for young people have been widely reported, connecting online has also allowed a lot of Black youths to foster a sense of community. A survey by the organisation Conscious Youth found that “Racism”, “Black Lives Matter” and “Bullying” were the most important topics to the young people aged 11-25 that were surveyed. “Social Media platforms have completely changed the way social movements form and grow,” Conscious Youth’s CEO and Co-Founder Serena Johnson told FE News. Of those surveyed, 75% said they felt more confident now than ever posting about causes they’re passionate about online, suggesting that social media can offer a safe outlet to find common ground. “Providing an online space has been life-saving for African heritage women”, Rose Lewis says about SISTAH SPACE’s social media platforms. SISTAH SPACE is an organisation that supports UK women of African heritage who have been affected by domestic and sexual abuse. “[Our] online presence gives Black women and our community a voice in [regard to] domestic abuse. It [also shows] them that they are not alone and that the wider community, options, and services are available”.

From economic disparity to racial prejudice, the reasons why Black people feel increasingly lonely in the UK are manifold. Reeves feels that the way to address this is through better mental health treatment. “We must guarantee access to mental health treatment in less than a month for all who need it because it is one of the most urgent needs of our time”, she says. “Labour’s plans to do this would see a radical expansion of the mental health workforce, resulting in over a million more people receiving support”. Mental health figures released last year indicated that Black people were four times more likely to be detained under the Mental Health Act than white people –– suggesting that Reeves’ concerns are not unfounded.

Despite this assertion, the conservative government released a report by the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities in March last year that claimed the “system is not rigged against ethnic minorities”. Unsurprisingly, the report was met with widespread criticism for being badly researched and lacking nuance. The Runnymede Trust also ran a report on race relations within the country last year and found that in some instances, the government’s approach to discrimination in the UK is making matters worse.

When Seleoane’s body was discovered, the company responsible for managing her building was asked for comment by the BBC. “We recognise that more could’ve been done”, said Ashling Fox, Peabody Trust’s deputy chief executive. It’s an understatement in Seleoane’s case, but a sentiment that the current UK government and our own communities need to take heed of.