Canva

Why protesting as an immigrant feels impossible

When protesting can affect your immigration status, who really gets to have a voice?

DiyoraShadijanova

23 Apr 2021

I attended my first (and only) protest a month after I was granted a visa to remain in the UK. Previously, I spent half a year figuring out a way to stay in the county as I’m a transgender person from Brunei Darussalam, a nation on the island of Borneo, where queerness is punishable by law and may result in a death penalty. Going back was not an option for me. But neither is remaining silent on human rights issues in my new home.

During the visa application process, I was extremely careful about anything I said or did so as to not jeopardise my precarious position. I thought that once I had a more secure immigration status, I’d be safe to express my views in the country I lived in. And so, in March 2020, shortly before the lockdown began, I assembled alongside a small group of protestors to campaign against the gendered segregation of bathrooms and the denial of access to gender affirming healthcare to young trans people.

It was initially comforting to be surrounded by a group of people who felt that their rights were violated by a political status quo in the same way that mine were. It was nice to feel as if I was able to say something to make things better for trans and non-binary people. However at one point something turned for me. After a short high of being surrounded by other trans people, which I didn’t have a previous experience of in Brunei, I started to feel a strange distance from everyone else at the protest. The disruption we were creating triggered my anxiety, as though I was unsafe. I guess my instincts as an immigrant kicked in: don’t push too hard or you’ll regret it.

“I thought that once I had a more secure immigration status, I’d be safe to express my views in the country I lived in”

Unfortunately it seems my discomfort around protesting is well founded. Last summer, the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants (JCWI) and Black Protest Legal support (BPLS) published a resource providing immigration advice for protestors during the Black Lives Matter protests. They clarified some of the unknown fears I had about the circumstances in which deportation or cancellation of my visa would occur.

The risk of being deported was lower than I thought, as automatic deportation would only occur if I had a conviction of longer than 12 months or a history of criminal convictions. Still, I was right for feeling safer by having a secure immigration status because I wasn’t completely safe. I still can’t afford to be arrested at a protest, as it would affect future immigration applications and this would bear serious consequences to my personal safety.

Not only am I fearful of being sent back home where I will be persecuted, but I also fear losing many of the things I’ve gained by living in the UK. Here I have access to gender affirming healthcare, the legal possibility of changing my identification documents to reflect my gender identity, I have the right to marry the person I love and some protection against employment discrimination.

There’s an anxiety that most immigrants, especially BIPOC immigrants, share. Immigration policy is designed to extract financial and human capital and therefore we have to act to suit Britain’s needs – not our own. Misbehaviour isn’t tolerated. And with the new Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill set in motion, who knows what will happen to protesting immigrants? We can’t afford to be arrested at a protest as it could result in the cancellation of our visas, jeopardise future applications or worse, there’s a risk of immediate deportation. These fears are also how the Home Office controls our behaviour to be obedient and uncontroversial.

“Not only am I fearful to be sent back home where I will be persecuted, but I also fear losing many of the things I’ve gained by living in the UK”

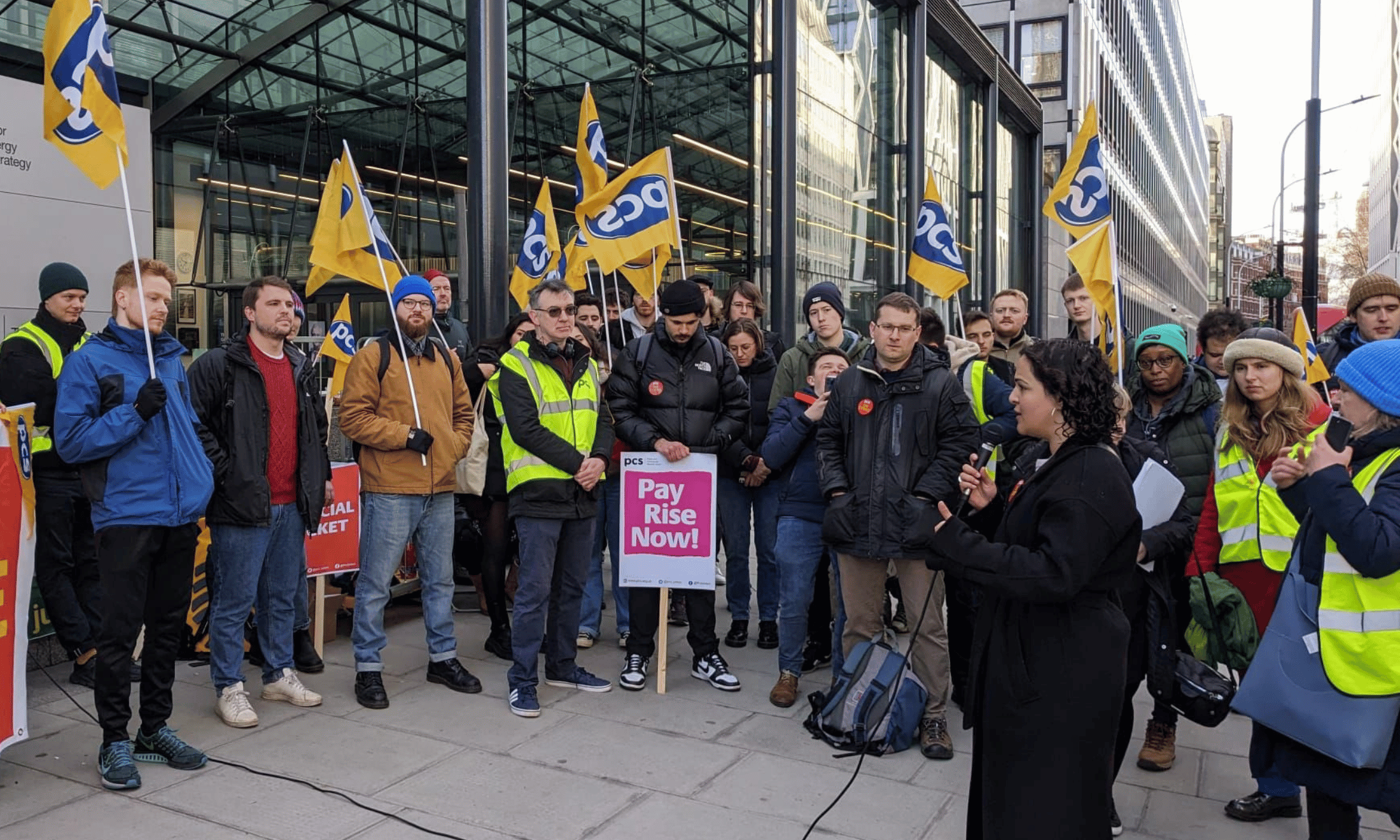

Fearing for my safety as a protesting immigrant, I decided to train as a legal observer with BPLS last November. As a legal observer I wouldn’t be a participant of the protest, but rather an independent observer monitoring police conduct on the ground. In a way, I wouldn’t be an actor within the sovereignty of Britain, but would be functioning to hold the police accountable to domestic and international law. At the time I thought this role resolved my concerns.

But even as a legal observer, I didn’t make it to my second protest. Police, despite what they say about their purpose in upholding the law, don’t seem to care about acting in accordance with it. In the past few weeks, legal observers from BPLS have been arrested and detained whilst volunteering at the #KillTheBill protests. There’s no doubt that their immigration status would have been checked while they were in custody.

“I find myself in the position that I have been for most of my life once again – being bullied into silence”

After lengthy deliberation, I decided it’s not safe for me to protest in any capacity at the moment. It’s extremely frustrating. I thought that since I experience an increased risk from the police, I should have the right to protest this bill in particular. But no, it seems only those who can afford to be arrested, those who will likely never experience the full terror of the police, get to have a voice on this particular matter.

My own lived experience gives me a specific insight into the atmosphere of fear and violence generated by the political establishment of this country. Staying silent as a result of this hostile environment is wrong, as I know that the discourse in many of these protests will dictate how I, among many other immigrants, will be treated in the future. But participating in protests also puts me in danger. It’s an impossible situation.

All I can do is stay at home, watch, and try to help from a distance. I find myself in the position that I have been for most of my life once again – being bullied into silence.

The identity of the writer is protected by a pseudonym