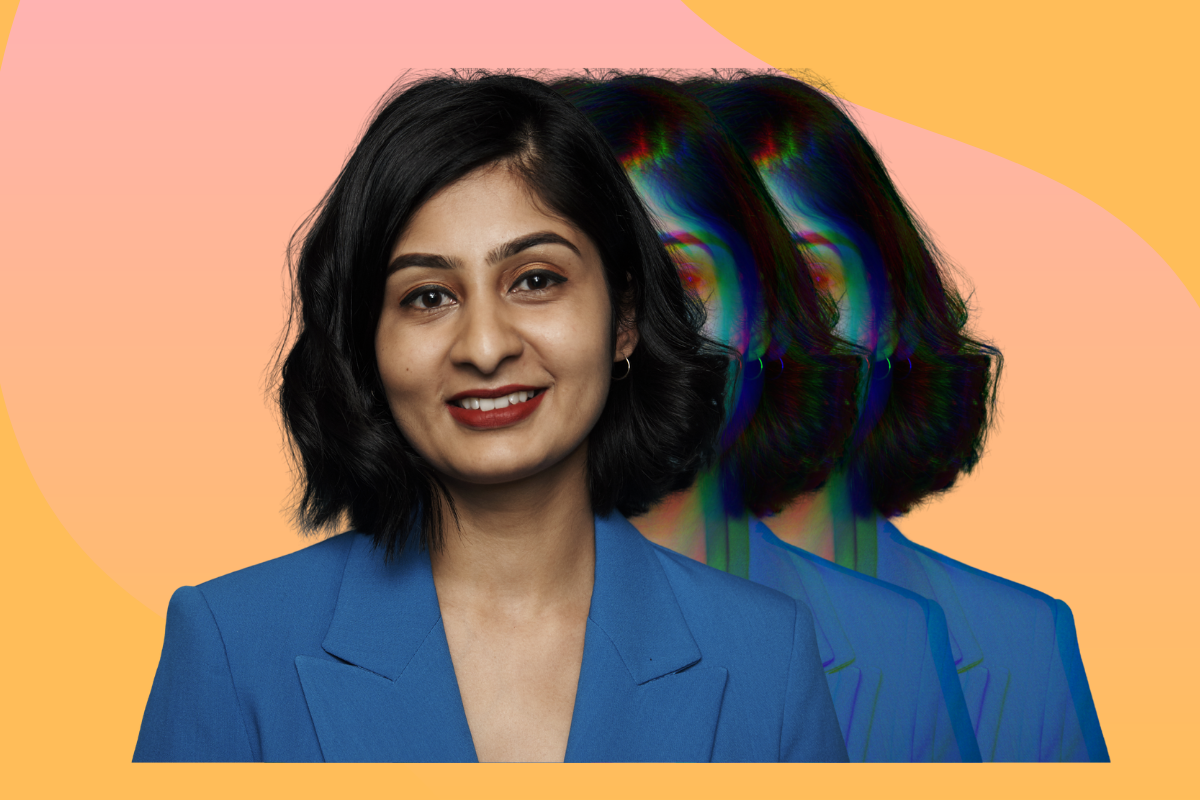

Annie Laymond

‘The future is ours – it has to be’: MP Zarah Sultana sets out her mission for change

Labour's MP for Coventry South explains how her West Midlands childhood set her on the course to fight for a better world.

Zarah Sultana

23 Jan 2020

Photography by Anne Laymond

When I was 14, a senior police officer said that every child in my school was able to name a gang they were going to join. In a few years, he said, the teenagers currently sitting in classrooms would be having gun fights in the city centre.

I grew up in a multi-racial working class community in inner-city Birmingham, part of Labour’s forgotten “heartlands”. My first political memories are the Iraq War, the War on Terror, and their impact, both at home and abroad. For us, it meant surveillance cameras on our streets and rising Islamophobia.

My family moved from Kashmir to the West Midlands in the 1960s. My grandad was one of the workers who helped make the region a booming centre for the motor industry. But during my teens, his old factory closed its doors. The bosses blamed cut-price competition from China and India. This was deindustrialisation in action and my region was hurting.

By the time I left school, the Tories and Liberal Democrats were in power. The student movement was defeated, tuition fees were trebled, and austerity became the order of the day. I went to university and was in the first cohort of students to pay yearly tuition fees of £9,000 (today, my student debt is nearly £50,000).

David Cameron and George Osborne – two Bullingdon boys who had enjoyed every privilege in life – made it their mission to attack the public services that working class communities like mine relied upon. It was class war, but no one called it that.

When I thought about politics, this is what I knew: illegal war, deindustrialisation, austerity and defeat.

The powerful have always told my generation what we couldn’t have. No free education, no secure work, and, fundamentally, no alternative to Margaret Thatcher’s economic settlement.

That meant accepting a system rigged for the rich, privatisation, unaffordable housing, and mountains of student debt. We were told these grievances were a fact of life. Power was for technocrats and big businesses, not us.

I got into politics because I refused to accept this.

That’s why in my first speech in Parliament, I said I wanted to end 40 years of Thatcherism.

Because there’s 40 years of damage to reverse, not just 10.

Don’t get me wrong, I know New Labour did many good things – my own family benefited from Sure Start and the national minimum wage. But even by its own account, New Labour didn’t want to transform the economic order for the working class. It accepted the basic tenets of Thatcherism.

As New Labour grandee Peter Mandelson said, they were “intensely relaxed about people getting filthy rich”. In 2002, he laid out New Labour’s stance in the plainest of terms, saying: “we are all Thatcherite now”. Tony Blair himself admitted that he saw his job as “build[ing]” on things Thatcher did, “rather than reversing them.” And let’s not forget that New Labour went along with scapegoating migrants and people of colour.

That’s not good enough for my community, my generation, or my class.

And now the climate emergency means that we have no choice but to raise our ambitions: If we want to save the planet, we have to break with the old order.

“The answer couldn’t be clearer: the climate crisis is a capitalist crisis”

This winter, we have seen Australia burn. 29 people have died, more than a billion animals have perished, and an estimated 10 million hectares of bush, forest and parks have been destroyed. At the same time, at least 66 people have lost their lives in floods and landslides in Indonesia. Entire neighbourhoods of Jakarta have been submerged in floodwater. Thousands have been forced to evacuate.

This is what climate breakdown looks like.

The science is clear: If we don’t act, then by the time I reach middle age, it will be too late – the climate emergency will become the climate catastrophe.

To stop that from happening, we need to name what’s driving the crisis. And the answer couldn’t be clearer: the climate crisis is a capitalist crisis.

It’s caused by the 100 companies responsible for 70% of global emissions, by billionaires who have got rich polluting our rivers, and, at root, by an economic system that puts the profits of the rich above the needs of the people.

Call it Thatcherism, neoliberalism, or free market capitalism if you want. Whatever we call it, if it has a future, we don’t.

The climate crisis will hit the working class hardest, wherever we are – be it Coventry or Canberra, Doncaster or Delhi – while the rich will build ever higher walls to protect themselves. That’s why the climate struggle is a class struggle without borders. It pays no attention to state boundaries. And in our solidarity, neither can we.

The only answers are radical.

Our future depends upon us uniting working people, in all our diversity, taking on the billionaires, the press barons and the big polluters. Brought together in our shared interest to achieve a global Green New Deal, we can create a better world.

“I want to look teenagers in the eye and say with pride: my generation faced 40 years of Thatcherism and we ended it”

This is how we rebuild Britain and save the planet – bringing green industries to the Midlands; providing good, unionised jobs; democratising the economy and eradicating poverty.

Ten years ago I was sitting my GSCEs at school. I never dreamed I would be an MP. In ten years time, at the beginning of the next decade, I want to look teenagers in the eye and say with pride: my generation faced 40 years of Thatcherism and we ended it. We faced rising racism and we defeated it. We faced a planet in peril and we saved it.

It’s not going to be easy, but I believe together we can do it. I hope you will join me.