Wikimedia Commons

As cities adapt to rising temperatures, some are deepening the climate crisis

In Qatar, eight World Cup stadiums have fully-functional air conditioning to keep players and fans cool during warm November temperatures.

Leila Sackur

15 Nov 2022

Dubai – the ultra-modern city-state beloved by influencers and property developers everywhere, famed for its underwater hotels, indoor ski slopes and chronic exploitation of migrant workers – has an innovative new offering for tourists hoping to escape the heat. City Walk, which was completed in 2016, is a 900,000 square metre, outdoor shopping development, roughly double the size of Vatican City in Rome. Replete with upscale gourmet restaurants, plush hotels, and luxury boutiques, those strolling through this desert Disneyland for shopaholics are unlikely to break a sweat.

Located on the beachfront Jumeirah district, it’s not the cooling sea breeze or particular access to shade that keeps the district chilled, but the addition of outdoor air conditioning jets atop each storefront, maintaining perfect temperatures across the slick, private streets. But along the back of the precinct – where visitors arriving by car or complimentary shuttle are unlikely to venture – buildings are lined with the air conditioning generators. Spitting out hot exhaust, these make the climate even more inhospitable for those who don’t have the fortune to live in one of City Walk’s 34 serviced apartment buildings, or funds for luxury hotels.

This year’s record breaking temperatures worldwide have prompted popular discourse on how cities should adapt to the climate crisis. Though many nature-based and passive solutions exist and could be implemented, harmful short-term solutions seem to dominate global adaptation practices. In Qatar, for example, eight World Cup stadiums have fully-functional air conditioning to keep players and fans cool during warm November temperatures.

However, investment in air-conditioning is a climate control solution that is not only financially inaccessible to most people, but also accelerates the extreme weather it is designed to mitigate, due to its obscene consumption of energy. The International Energy Agency predicts that globally, energy spent on air conditioning will triple by 2050 – an amount equivalent to all of China and India’s current electricity usage put together.

“The International Energy Agency predicts that globally, energy spent on air conditioning will triple by 2050”

It seems that artificially manufacturing the perfect local climate can even accelerate climate breakdown. As it stands, urban places are not only ill-prepared for heat catastrophe, they’re also a major contributing factor in the climate crisis. In particular, cities – where the majority of businesses operate and goods are produced, transported and traded – consume 78% of the world’s energy and produce 60% of greenhouse gas emissions. They’re also up to 10C hotter than neighbouring rural areas, due to the urban heat island effect, where the dense concentrations of pavements, roads and buildings absorb and retain heat.

In poor and working-class areas, this effect can be even more pronounced. They’re disproportionately likely to be located along polluting main roads and face public disinvestment in parks and tree cover (which provide shade and store less heat than concrete sidewalks and buildings) – the result of which is even higher rates of air pollution, heat-sickness and mortality.

‘Passive design’

So how can we make cities that are better-prepared to withstand extreme temperatures without exacerbating their cause? Rosie Murphy, the Diversity and Solidarity Officer for Architects Climate Action Network (ACAN), a UK-based group taking action on climate breakdown within the architecture and construction industries, suggests passive design could provide sustainable solutions.

These might look like designing buildings to utilise elements of the environments that they’re in, lining them with windows and vents instead of using air conditioning devices, and positioning the building to maximise the sun’s warming potential as an alternative to radiators. The Goldsmith Street development, built by Norwich City Council, is one example.

The collection of airtight houses – arranged around tree-line squares and featuring roofs designed to maximise sun in winter and shade in summer – is proof of social housing’s potential. But given that 80% of the houses that will exist in 2050 have already been built, there is also a need to retrofit existing housing stock for sustainability. Since most private and social tenants have little choice over the physical conditions of their housing, retrofitting has become a central campaign of branches of organisations such as the London Renters’ Union and Manchester’s Carbon Co-Op, as well as architect-led activist networks such as ACAN itself.

It’s not just housing that people can use to activate their environments against the climate crisis. In New York City, community gardens – which trace their roots to Black and Puerto Rican guerilla garden movements – continue to be maintained. They give their surroundings some protection from extreme weather in the form of tree cover and stormwater absorption.

Addressing inequality as a key priority

Across the world, the problem is that inequality – including unequal access to land and housing – is the byproduct of capitalism, whereby the poor pay for climate crisis with their lives. Geographer Neil Smith writes that there is no such thing as a natural disaster; that the causes, vulnerability to and scale of response to calamitous “natural” events are in fact the products of tangible social realities.

“We’re expecting property developers to care about our lives when they don’t”, says Adam Almeida, a senior data analyst at Common Wealth think tank. Corporate-sponsored urban greening projects such as New York City’s Highline or London’s Marble Arch mound monstrosity “are made in the language of community assets and family run businesses because [corporations] know they can’t continue to market in the same way, but realise how valuable of an asset land is,” said Almeida.

“Climate adaptation plans created in the interests of capital, not in terms of the needs of people, produce spaces which are socially partitioned and materially unsafe for those living on or outside the margins”

Nearly 6,000 miles from Dubai’s planned location for the Mall of the World, construction work on the new fortified suburb of Eko Atlantic in Lagos, Nigeria is also ramping up. The city, designed to be “energy-efficient and [with] environmentally-friendly materials,” according to the development’s website, is being surrounded by a sea defence barrier of 100,000 concrete blocks to protect against rising sea levels. Those who build and service it – construction workers, chauffeurs and chefs – live outside the walls of the parameter and are made more vulnerable to sea level rise and extreme heat by the sea walls that lock them out.

Though the project is green-building certified by the International Finance Corporation, the construction work required is itself inherently unsustainable. Equally unsustainable is the dispossession of nearby island and slum dwellers whose homes are threatened by being outside the sea wall, which causes higher tides outside the block. As a suburb only for the wealthy, Eko Atlantic goes no way to address Lagos’ actual housing need.

Climate adaptation plans created in the interests of capital, not in terms of the needs of people, produce spaces which are socially partitioned and materially unsafe for those living on or outside the margins. Priti Mohandas is an urban researcher focusing on state-provided transitional housing for informal dwellers and people experiencing homelessness in cities such as Cape Town and Mumbai. She told gal-dem that governments’ “cheap and rapid housing delivery programmes result in poor building fabrics, inadequate shading, lack of ventilation, high densities, and cramped living spaces.”

In poorly ventilated homes, such as those provided under the Slum Rehabilitation Act in Mumbai, spending further time in the home and cooking with kerosene gas also produces gendered health implications, according to Mohandas. In both examples, where long-term financial investment is figured only as a luxury for the rich, the end result is climate apartheid.

Community-first design

Murphy and Mohandas agree that there is a need to greater involve residents in the decision making of urban design and in the process of house-building itself. Addressing the climate crisis must be done in tandem with addressing the multidimensionalities of poverty and trauma. Governments chasing cheap contracts with developers are doomed to fail, no matter the quality of housing, if they don’t take networked approaches with grassroots local organisations that address the community’s long-term climactic, social and psychological needs.

“I personally hate this resilience narrative that has been emerging,” said Mohandas. “The vulnerable are already resilient, they don’t need big institutions trying to make them ‘more resilient’. What is needed is iron clad policy that acknowledges their vastly complex realities and takes responsibility to break the structural systems that create and perpetuate them in the first place.”

“Cities are unsustainable when controlled by speculators and developers”

Murphy focuses on public education and inclusion in architectural design. “The [lack of] skills, knowledge and access for people to get involved in the built environments around them has led to a disempowered society. Not only disempowered, but exhausted of yelling for necessary changes.”

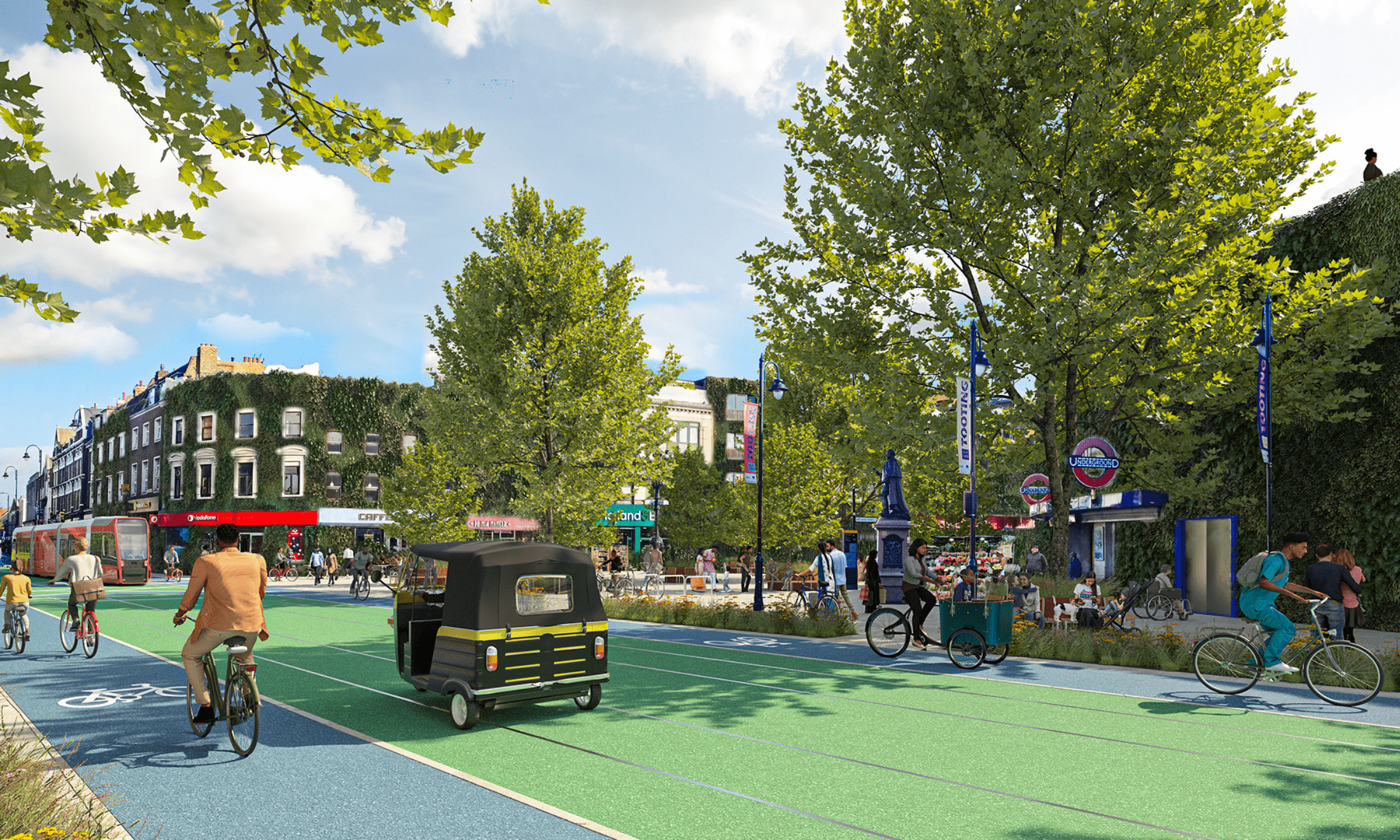

Public self-build projects, such as Nubia Way in Lewisham, a collection of houses built by African Caribbean activists and community members built according to the DIY principles of architect Walter Segal, are examples of how communities can cheaply create safe environments for themselves as resistance to racism and housing discrimination. In Tottenham, Save Latin Village won a campaign resisting the demolition of the historic Seven Sisters indoor market and its replacement with luxury apartments, and have received support from Haringey council for their own community-driven regeneration plan.

Cities are unsustainable when controlled by speculators and developers. They eat up land to churn out endless luxury high rise, asphalt roads and guarded shopping malls, making heatwaves more intense, surfaces less permeable for flooding, and polluting the air we breathe. Despite the vulnerability of cities, the climate justice movement – founded upon feminist and anti-imperial movements both past and ongoing – will be built out of connections made on city terrain. On urban ground, defending ourselves and our communities against climate breakdown is to rebuild our own housing, to resist demolition in favour of repair, and to prioritise the public ownership and control of resources in our campaigning – from housing, to transport, to land.

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?