Belgium has apologised for its abuse of mixed race children – it’s time for Ireland to do the same

Charlie Brinkhurst Cuff

11 Apr 2019

Image via Métis Association of Belgium / Facebook

The apology from Belgium’s prime minister, Charles Michel, for the segregation, kidnapping and trafficking of as many as 20,000 mixed-race children in the Congo, Burundi and Rwanda, is long overdue. Forcibly taken from Africa to Belgium between 1959 and 1962, métis children born in the 1940s and 50s were left stateless. If you’re not aware of the atrocities of colonialism (Belgium was responsible for the deaths of between 10 to 15 million Africans), this type of identity-destroying abuse might feel hard to comprehend – especially situated in such recent history. But in the UK, we have our own unresolved issues with the treatment of dual heritage children slightly closer to home: in Ireland.

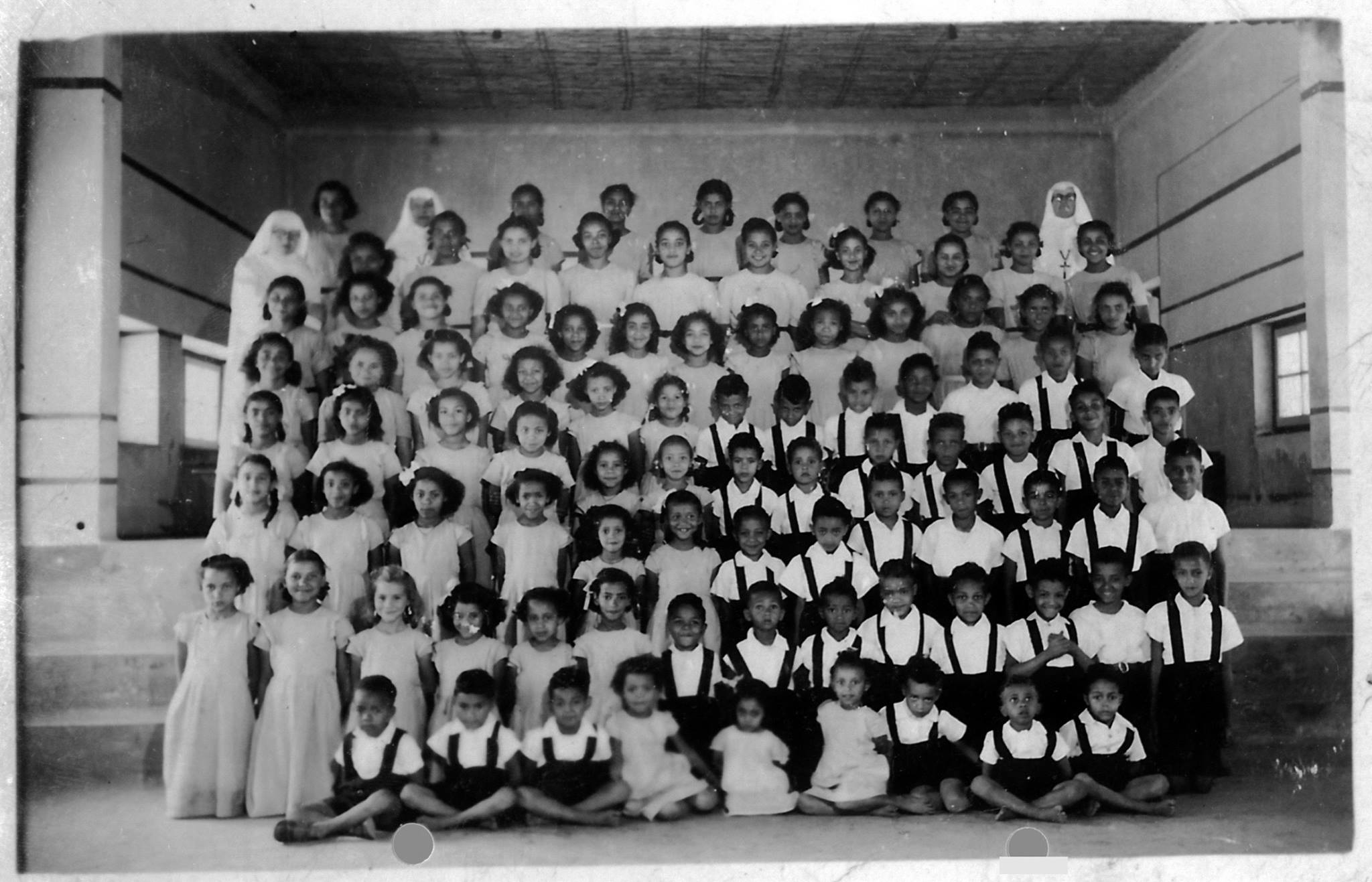

The correlations between the cases are striking. In Belgian colonies, many métis were brought up in Catholic institutions or orphanages, away from family and sometimes removed from where they were born. “These children posed a problem. To minimise the problem they kidnapped these children starting at the age of two… The Belgian government and the missionaries believed that these children would be subjected to major problems,” Francois Milliex, the director of the Métis Association of Belgium, told RFI.

Similarly, in Ireland, it has been documented that mixed-race children were left to rot in mother and baby homes and industrial schools in the 1940s to 60s. The Catholic Church was involved – nuns and priests would often run the homes and schools. “To be Irish was to be Roman Catholic. To be Roman Catholic was to be Irish,” says Rosemary Adaser, who co-founded the Mixed Race Irish campaign and support group for victims of the homes and schools. “It wasn’t uncommon for the Roman Catholic Church to send over its priests to the Irish community in London and give them lessons in morality.”

According to The New York Times, documents show that métis children, born to black African mothers and white Belgian fathers, were viewed by the church and state as undermining official segregation policies. They were a threat that might overthrow the colonial establishment, and so it was decided that they must be divorced from the black community. Snipped and thrown away from their mothers permanently. In Ireland, the situation was somewhat reversed: white women who had children out of wedlock, and specifically those who did so with black African fathers, were systematically forced into giving their babies up.

“Special attention seems to have extended to racist assaults which served to compound the physical, sexual, emotional and mental abuse”

Emma Dabiri

Ireland in the mid-20th century was a deeply racist place and even today it does not have effective hate crime legislation. Unlike their white peers, there is evidence that mixed race Irish children left in homes were never offered up for adoption; never given a second chance at life with a loving family. As Irish-Nigerian academic Emma Dabiri writes in her new book, Don’t Touch My Hair, “Mixed-race people I met, certainly those who were any older than me, had grown up in institutions… According to the alumnae of these abhorrent facilities, this ‘special attention’ seems to have extended to racist assaults which served to compound the physical, sexual, emotional and mental abuse many of the children were subject to.”

Rosemary has spoken in depth about the racism she suffered in a mother and baby home and subsequently at an industrial school. The subject of a Guardian documentary in 2017, she explained that she was called “blackie”, “nigger”, “golliwog” and “rubber lips”, made to go without food and wouldn’t be allowed to wash because they said her “dirty skin” would muddy the water. Her experiences aren’t unique: as Emma highlights, racist slurs, physical abuse and sexual stereotyping were all common.

“The Mixed Race Irish campaign is challenging the Irish government on the structural racism that was in play 60, 70 years ago,” says Rosemary. “Long before people knew what structural racism was even about, Ireland effectively had removed our rights to such an extent that we were denied our identity both as members of the African diaspora and also Irish people.”

It took years of campaigning from The Métis Association of Belgium for the métis to receive an apology from the church in 2017, and this more recent apology from the government has happened at least in part due to UN pressure. At the moment, Mixed Race Irish, who have identified over 100 victims but estimate figures to be much higher, are putting some of their hopes into an ongoing commission investigating mother and baby homes. Almost everyone from the campaign has submitted evidence to the commission, but at present, the government is yet to hint at making amends. The commission was originally set to report in 2017 but it has been pushed back to February 2020.

“I have to be optimistic that the rightness of our cause will be recognised by the mother and baby commission because us mixed race infants were treated very differently to white Irish children,” Rosemary tells me, explaining that Ireland doesn’t like to see itself as a country that has a problem with race relations. “This will be a very new position for Ireland because unlike Belgium or any of the other European countries, Ireland was never a colonial power. There’s a certain tension along the lines of that ‘the Irish were colonised by the Brits for 800 years’. But although it was not a colonial power, it had a symbiotic relationship with the Roman Catholic Church.”

“This will be a very new position for Ireland because unlike Belgium or any of the other European countries, Ireland was never a colonial power”

Rosemary Adaser

As Rosemary points out, the mixed race Irish community is the oldest living community of people of African descent in the country, and it’s crucial that they get recognition, an apology, and access to records held by the institutions they were once mistreated by (access to official records is something the métis are also still campaigning for). She also believes that if the commission were to agree with how the Mixed Race Irish campaign sees past events, “it would really help the current generation of mixed race and black African children in Ireland”. There’s no doubt it would be a validation of the issues with racism still suffered by young mixed race and black people, especially as both in the UK and Ireland, we don’t always know or have access to the traumatic, but relevant, aspects of our history.

Beyond Ireland, after WW2, the Telegraph reports that thousands of mixed race children born to black American GI’s stationed in the UK were given up by British mothers and sent across the Atlantic after the Home Office decided that “the child will have a far better chance if sent at an early age to the US than if it brought up in this country”. This wasn’t as honourable a decision as the Home Office made it seem: it was clear that mixed race black children were unwanted on British shores and cruelly separated from their loved ones. The UK is not an innocent party when it comes to systemic abuse either.

But back to Ireland, is an apology from the government at all likely? “We’re holding our breath, Charlie,” Rosemary tells me. “We’re holding our breath.”