Photography by @heardinlondon

Today, Black Lives Matter protestors have blocked the motorway leading to Heathrow, and, despite ongoing police brutality and deaths, there still seems to be some confusion as to why the movement is so important in the UK.

Philando Castile’s death has been watched by thousands of people. He is sitting in his car in Falcon Heights, Minneapolis, white t-shirt blooming red with blood, arm held crookedly, head thrown back in pain – leaning, it seems, almost as if to get further away from the man who has just shot him, police officer Jeronimo Yanez. Sitting next to him his girlfriend Diamond Reynolds, filming, is eerily calm but seconds away from hysteria. She narrates the scene which she is live-streaming to Facebook. “Please officer, don’t tell me that you killed him,” she begs Yanez who’s breathing heavily in the background, gun still pointing at Castile, “He was just getting his licence and registration.”

It’s a modern tragedy, but one we’ve seen all too often in a country where, according to a study by the University of California, “the probability of being black, unarmed and shot by police is about 3.49 times the probability of being white, unarmed and shot by police”. In the past few weeks I have been unsurprised at the subsequent protests that have littered parts of America under the Black Lives Matter banner – a campaign group which organises against police brutality and racism and which has also spawned the eponymous hashtag on social media.

While as an ethnic minority in the UK my experiences of racism are not quite as brutal, I can still relate to the fear and anger that systemic prejudice can bring. I am used to small instances of trouble – being called a nigger on the bus, a paki (yes) in the street, feeling out of place at work, being told by an accquaintance that she believes all black men are gang rapists – but there is little more terrifying than realising that people like you are actually dying in state-sanctioned violence because of stereotypes associated with the colour of our skin. However, along with the inevitable cries of “don’t all lives matter?” from those who struggle to make the distinction between being “pro” black lives and “anti” white, even amongst black people there has been some surprise that the Black Lives Matter movement has travelled to the UK.

Protests have happened in Manchester, Nottingham and Bristol since the deaths of Castile and Alton Sterling (who also died at the hands of the police in early July), whilst in London thousands of protesters actually brought traffic to a standstill. Chatting with 18-year-old Capres Williams, who organised the biggest London protest, she says that she was spurred on by watching the video of Castile’s death. “I thought, why hasn’t anyone done anything in the UK? London is such a diverse city, and I was so shocked that no-one had thought to set it up. I understand that police brutality isn’t as bad over here as it is in the US at the moment, but racism still does exist. I personally believe the police force in the UK is a racist institution.”

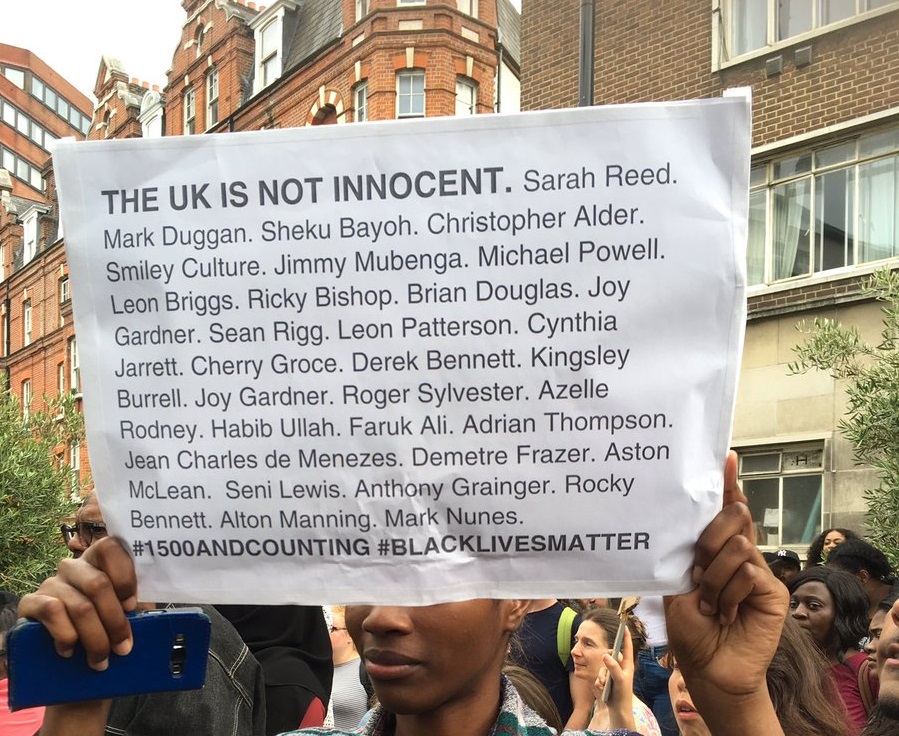

And in reality, while some people might be confused by Black Lives Matter protests occurring in the UK, demonstrations and riots caused by racial tension have been ongoing since the 20th century. In 1958 rioting broke out after a crowd of white men attacked a Swedish woman because she was married to a black Caribbean man. In 1981, Brixton, over 300 people were injured during riots caused by the police using stop and search tactics on more than 1,000 people in six days. In 2001 British Asians clashed with racists in Bradford. 2011 saw the death of Mark Duggan, a black man who was shot by police in Tottenham, and I remember the subsequent English riots that took place during that swampy summer before I started university; punctuated by the heat of riot-fires in Liverpool, Bristol, Croydon.

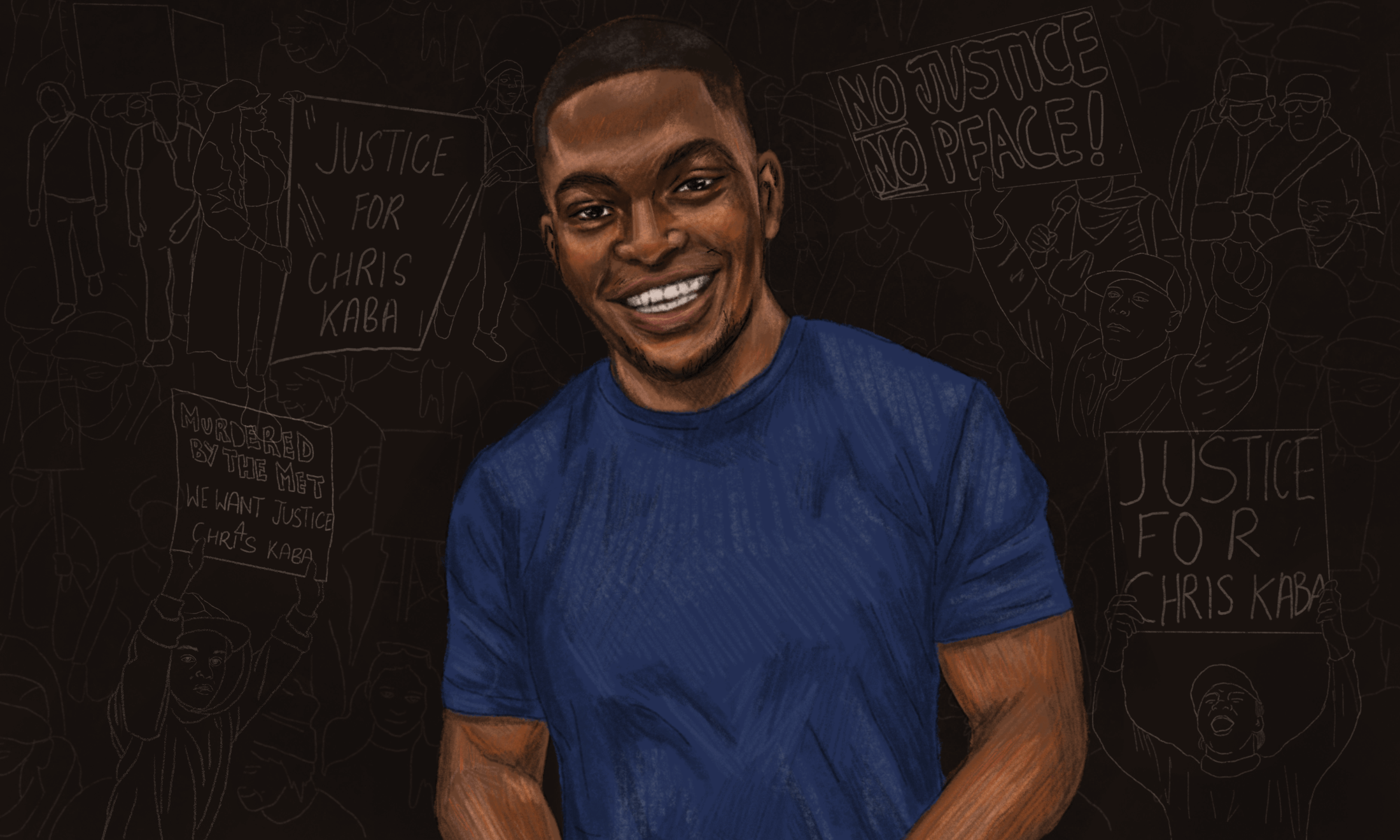

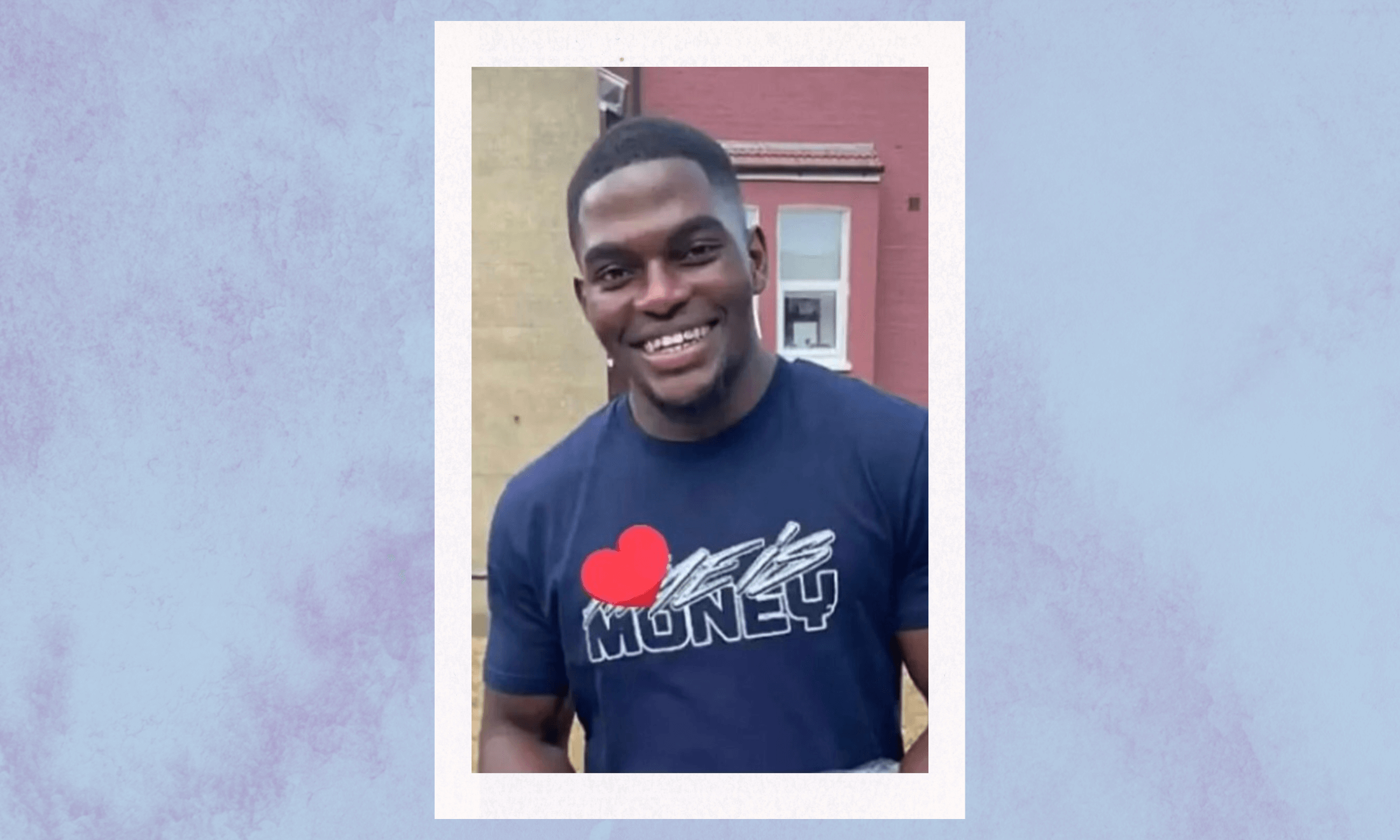

Apart from riots, a black family friend has been stopped and searched more than 50 times since he was a teenager. 2014 figures found that we make up 10 percent of those incarcerated, despite only being 3 percent of the population overall. More recent injustices have seen investigations launched into the deaths of Sarah Reed, who died in Holloway prison after having been the victim of a terrible police brutality case in 2012; Sheku Bayoh, who died in police custody under suspicious circumstances in 2015, and Mzee Mohammed, who died only a few weeks ago after being restrained by police officers in Liverpool. All three were black, and in a video which shows Mohammed handcuffed, laying prone on the ground, a police officer bids the person filming to stop. “Given the history of the police with black people I think I should be filming, that everyone should be filming,” comes the reply.

Sadly, in a post-Brexit world which saw a wave of racism endemic of deeper problems in our society, I think the time couldn’t be riper for Black Lives Matter to take up the mantle in the UK. Because the racism here is so insidious, even I sometimes get surprised when I hear my friends mention how they’ve been treated by racists. As well as violence against black people, we have the Prevent agenda and anti-terrorist legislation making life difficult for ethnic minorities from visibly Muslim backgrounds.

One point that has been raised is that, seeing as black people are such a tiny minority in this country, shouldn’t there be another slogan that encompasses people – say – of Asian heritage as well? “When we say Black Lives Matter we are not saying that people of colour who aren’t black are not experiencing racism,” Imani Robinson, a social justice campaigner at Matters of the Earth, tells me. “But we are saying that black people experience a particular kind of racism.” It makes sense. Unlike the visibly south Asian kids at my school I didn’t ever have the indignity of being labeled a “terrorist”, just as they are able to empathise but not relate to the racial prejudice I suffered.

It seems like there’s a new video coming out each day of a black person being shot by the police (just a few days ago Korryn Gaines was killed and her young son injured during a standoff with police), but the video that has stayed with me most is Castile’s. It’s too traumatic to be watched more than once, but the sound of Reynold’s 4-year-old daughter, Dae’Anna, who was in the car at the time of the shooting, saying “it’s okay Mommy. It’s okay, I’m right here with you,” is one of the most heart-breaking things I have ever heard and reminded me of the humanity that lies at the source of the Black Lives Matter campaign. They exist so no little girl is ever forced into a situation where they are protecting their mother like that again; and that sentiment is global.

As the Black Lives Matter team said in a recent statement: “The US, UK and our Black family all over the world are standing together, as we always have. It is our Black diasporic radical tradition. It is how we will win.”