Wikimedia Commons

10 years on from the London riots – how much has police violence changed in Britain?

Black Lives Matter UK reflect on a decade of policing and resistance, and their vision for racial justice in the years ahead.

Black Lives Matter UK

04 Aug 2021

This week marks 10 years since the seismic London riots, the most prolonged and widespread unrest seen in the city since 1780. The uprising was sparked by a distressingly familiar scene in the long-running story of Black dissent in Britain: the police killing of a young Black man. His name was Mark Duggan, and he was fatally shot in his hometown of Tottenham, north London on 4 August, 2011.

Mark’s case exposed police incompetence on a number of counts. Rather than the London Metropolitan Police informing Mark’s family of his death in the hours after his death,, the Independent Police Complaints Commission disseminated false and misleading information of a “shootout”, claiming to the media that he had fired at police first. It was later revealed that the 29-year-old hadn’t shot at officers at all, but rather a police officer had accidentally shot one of his colleagues, and tests showed no forensic evidence that Mark had held a gun at the scene.

After violence erupted between police and protesters during a community protest led by Mark’s family at Tottenham Police Station on 6 August and violence erupted, dissent soon started spreading to other areas in London and beyond. From 6 – 11 August, over 60 locations reported disturbances in cities and towns across England, making them the largest wave of riots across the UK since the 1981 ‘Brixton riots’.

Today, there might be a temptation to eulogise the events of 2011 as those of a bygone era. In many ways this is unsurprising; Britain’s then-Prime Minister David Cameron went to great lengths to frame Mark’s killing as a failure of an otherwise functioning police force (suggesting that the solution was “more police on our streets”), and distanced the uprisings from politics. Most notably, he claimed the riots were “used as an excuse by opportunist thugs“, and went on to declare a racialised “all-out war on gangs and gang culture” in response. As part of this punitive performance, Cameron ensured that the consequences for the disproportionately young working class people of colour detained in the 2011 uprising were extreme – the unrest resulted in more than 3,000 arrests and countless raids, increased stop and search and other instances of police violence and harassment.

“Following a decade of protest against the state-sanctioned murder of Black people, the events of 2011 were not happenstance. On the contrary, they were a response to deeply violent material conditions”

But the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement in the years since Duggan’s death tells a very different story to that of politicians and pundits. Following a decade of protest against the state-sanctioned murder of Black people, the events of 2011 were not happenstance. On the contrary, they were a response to deeply violent material conditions.

In 2011 and 2021, Black people in England and Wales have found themselves the disproportionate targets of Tory austerity, and of police harassment, violence and killings. Casting our lens further back into British history, the through-lines persist – just as the 2011 riots took place against a backdrop of the racist use of stop and search and Section 60 powers, the Black communities involved in the 1981 Brixton Rebellion were partly rebelling against the infamous ‘sus’ laws, which were disproportionately applied to Black people under Margaret Thatcher. This pattern of oppression and uprising recurs for virtually every generation living under racist state violence in Britain.

Of course, some things have changed in the last decade. While news of Duggan’s death was circulated on platforms like Facebook and Blackberry Messenger, the exponential increase in smartphone and social media use has continued to change the way we document and circulate instances of police violence. Now, it is faster and easier to disseminate information and to galvanise people on the ground. In the US, Black Lives Matter protests have been further fuelled by footage of the deaths of Black people including Eric Garner in 2014, Philando Castile and Alton Sterling in 2016, and George Floyd last summer– although the trauma this can represent for Black social media users should not be underestimated.

The 10-year period since the riots have also seen a significant movement-building effort in the US, the UK and globally. From the first use of the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter in 2013, to the founding of Black Lives Matter UK in 2016, the flames of resistance were lit in the last decade, and now continue to blaze. The Black Lives Matter umbrella – which comprises many independent groups and approaches – has also been crucial for consciousness-raising and political education; it has provided many with the analysis and language to connect the dots between different forms of racist state violence across history and across borders. This includes the murder of Mark Duggan, whose life mattered.

“This week, as we remember the 2011 riots, we are conscious that the racist state violence that sparked these uprisings is still very much with us, and has intensified”

There are also deeply harmful legacies left by David Cameron’s response to the riots. Under Theresa May and Boris Johnson, the Conservatives’ “all-out war on gangs” has continued, with gangs databases filled with young Black men’s names. Armed police officers also more frequently use tasers, spithoods, firearms and other weapons in a context in which Black people are more likely to be on the receiving end of police violence. So-called ‘gang injunctions’ limit freedom of movement and association, specifically targeting young Black musicians as politicians, and police criminalise Black culture. Here, there are clear echoes of the policing of the blues dances of the 1970s and 1980s, of Notting Hill Carnival, and of grime raves. Nearly twice as many people are imprisoned today as they were during the 1981 uprisings, and the Lammy Review in 2017 found that Black Britons are now more likely to be imprisoned than Black people living in the US.

This week, as we remember the 2011 riots, we are conscious that the racist state violence that sparked these uprisings is still very much with us, and has intensified, exacerbated by an social context that still sees many Black and brown individuals treated like second-class citizens, unless they have been anointed a footsoldier of the establishment. We also remember that as long as the state continues to brutalise Black people, criminalise our way of life and repress resistance, we cannot let them divide into those who protest using the ‘proper’ channels, and those who do not. Even the most peaceful methods of Black protest are subject to intense scrutiny by the media and the state. The mobilisations in the summer of 2020 were met with the same riot cops, police horses and tear gas as the 2011 riots.

Now – in response to the protests of 2020 – organisers face the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, which proposes a clampdown on our right to protest, and to once again expand the racist policing Black people have been resisting for decades. In the face of an increasingly racist Conservative government, the outlook may be bleak, but since 2020, Black Lives Matter UK has only continued to build coalitions, to raise hundreds of thousands of pounds to give to other Black-led grassroots groups, and to work towards strengthening a mass anti-racist movement in the UK.

Standing alongside groups like Sisters Uncut, Gypsy, Roma and Traveller Socialists, 4Front, Northern Police Monitoring Project, Sistah Space, African Rainbow Family and B’ME Cancer Communities, our vision for racial justice is anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist, feminist, and disabled, queer and trans inclusive. Crucially, it centres Black communities, who are still seeing the impacts of the London uprisings ten years on. If, as Martin Luther King Jr. said, a riot is the language of the unheard – then it is our duty to reflect on these voices, and to organise a movement that cannot be ignored.

To be ungovernable: on the history and power of Black anarchism

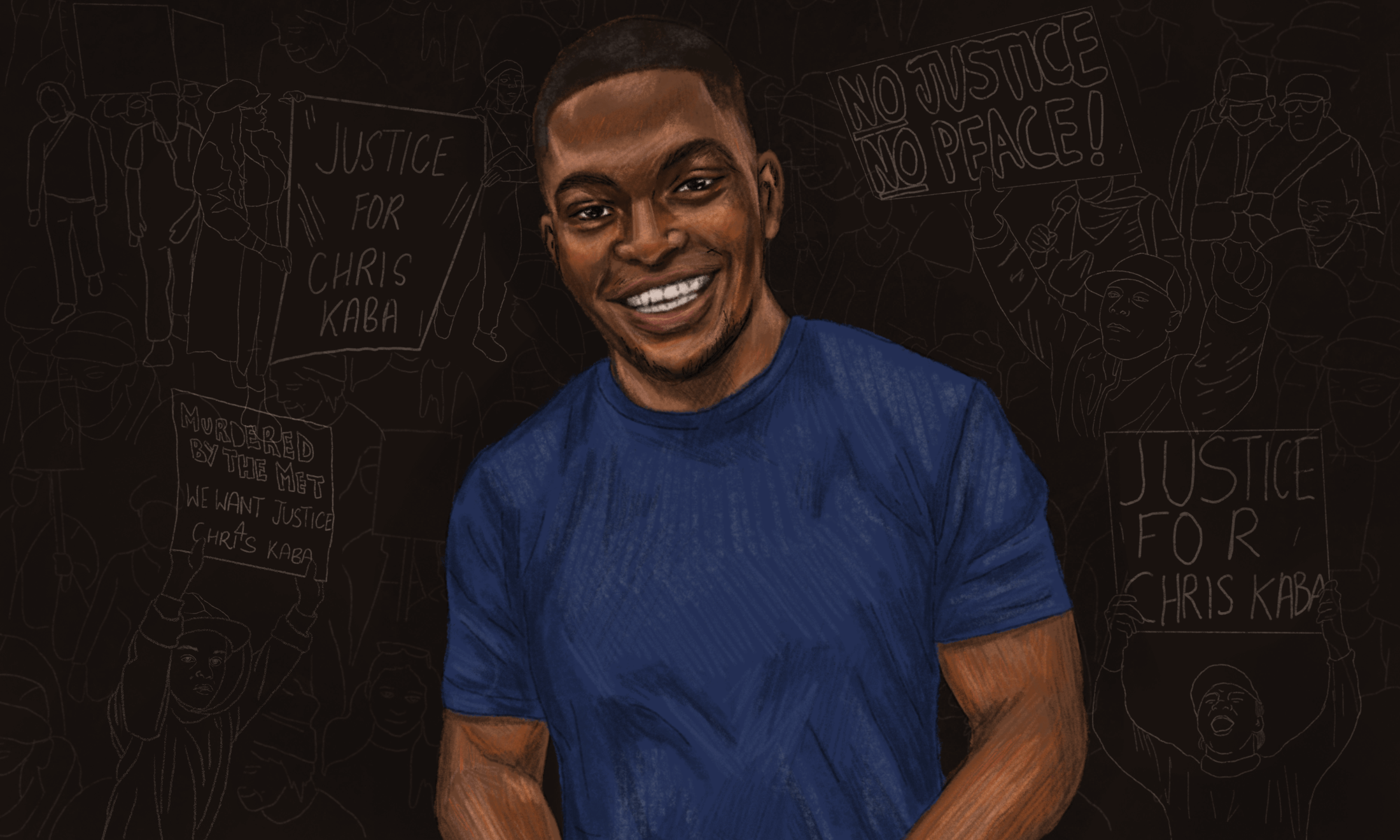

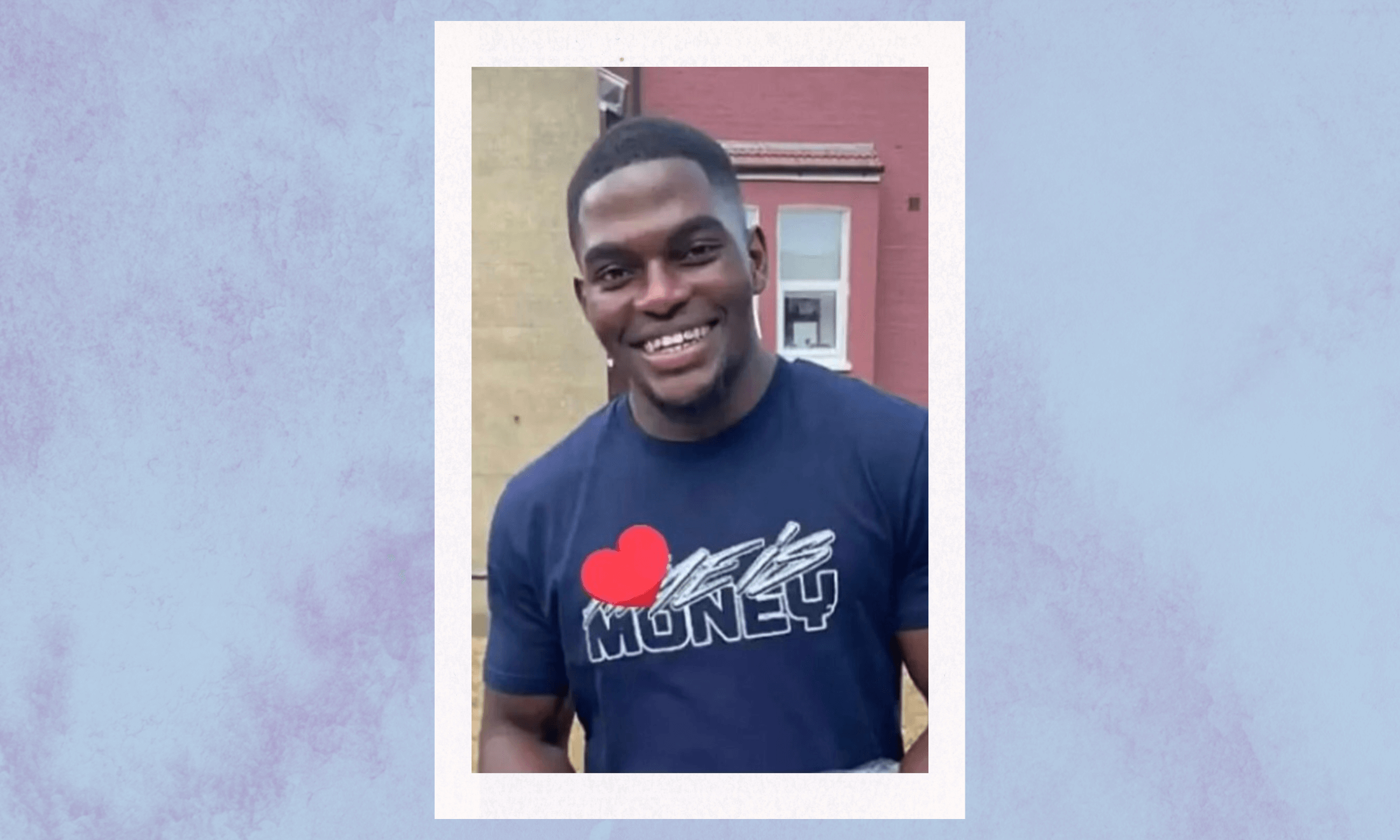

‘He showed and valued love’: Chris Kaba’s family and friends continue their fight for justice

Bell Ribeiro-Addy MP on grieving Chris Kaba, and holding the Met Police accountable