Khadija Said

‘He showed and valued love’: Chris Kaba’s family and friends continue their fight for justice

The Met Police killed Kaba on 5 September. In their calls for justice, his family grieve a loving son, friend and father-to-be.

Faima Bakar

26 Sep 2022

Content warning: This article contains mention of racism.

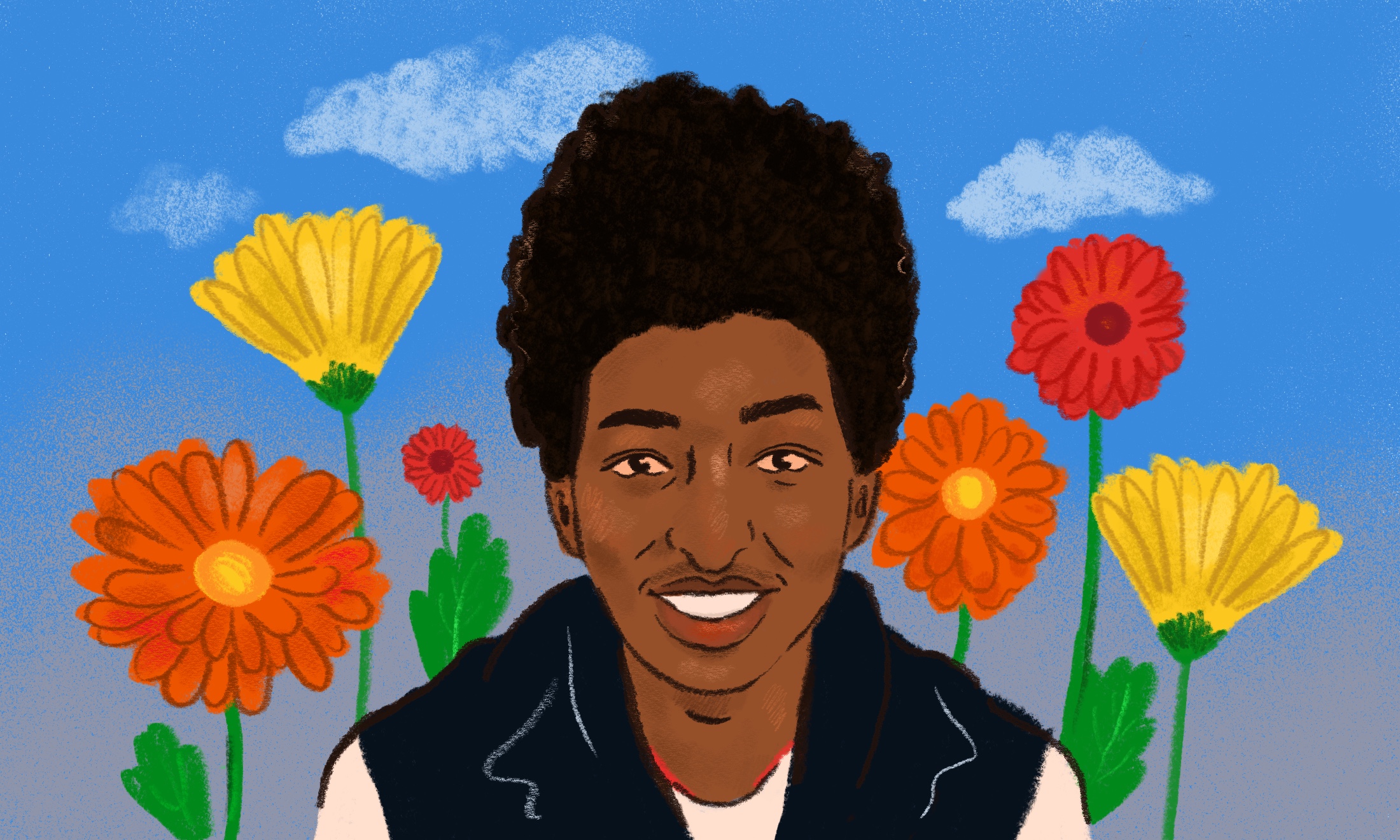

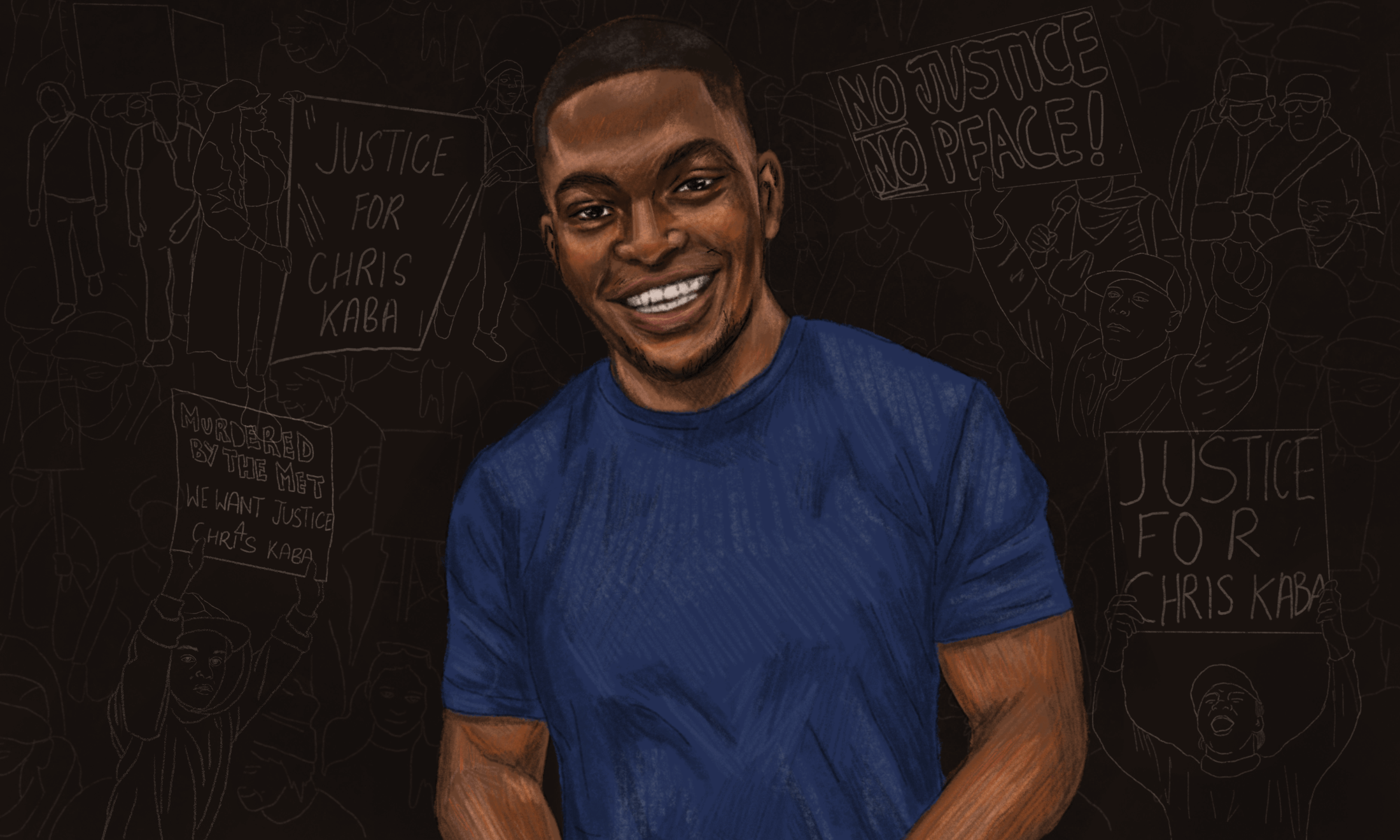

Crowds of mourners fill Westminster’s Parliament Square, surrounding a grieving family in the centre. Helen Nkama and Prosper Kaba, parents of 24-year-old Chris Kaba who was killed at the hands of the Metropolitan Police, sit clasping their palpable distress. Those who knew him wear a crisp white T-shirt, with a picture of his beaming smile.

Just a week prior, on Monday 5 September, Kaba was driving an Audi in Streatham, south London, which was flagged by Automated Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) for being involved in a firearms incident. Police officers chased the car, boxing it in. A Met officer then fired a single shot through the driver’s side of the windscreen, killing Kaba.

The Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) later confirmed Kaba was unarmed, and the car that had been flagged previously was not owned by him.

Since the shooting, the officer who fired the gun has been suspended from frontline duties and the IOPC has ruled it a homicide investigation. The killing has again called to question the oppressive mechanisms of police brutality as Kaba is now the fourth Black man to be shot and killed by police while unarmed in the past two decades. He joins the tragic list of victims who lost their lives in a similar way, including Mark Duggan, who was shot dead in Tottenham in 2011, Azelle Rodney, killed in 2005, and Jermaine Baker who was fatally shot in 2015.

In England and Wales alone, there have been at least 1,833 deaths in police custody or following police contact since 1990; a figure that disproportionately impacts Black and minoritised communities. “Policing […] inflicts immeasurable harm and trauma on Black communities every day,” says a spokesperson from 4Front, a youth empowerment organisation. “We see this from surveillance tools (such as gang databases), to strip searching, to the use of force – Black people are disproportionately targeted and impacted.” In the UK, Black people are nine times more likely to be searched by police than white people.

Through their grief, the family continue to call for accountability for the Met’s failings. They say it took 11 hours for the police to inform them of Kaba’s death, and that the officer was only suspended after facing pressure from the public.

The protests that have taken place in London since Kaba’s death two weeks ago, have seen thousand-strong crowds march outside Scotland Yard. In their demands for justice, friends and family also want to remember the person he was, not only the circumstances of his unjust death. gal-dem spoke to Kaba’s loved ones who want the world to know that he was so much more: he was a father-to-be, a fiancé, an eldest child, a joker, a dancer and rapper.

“Chris was the life of the party. When he walked in, he was immediately the centre of attention”

Jefferson Besola

Kaba’s cousin Jefferson Besola, 27, says the ordeal feels like a nightmare, one that he expects to wake up from.

He recalls a poignant memory of his youth spent with Kaba. “One of my favourite moments with Chris was when I hadn’t seen him in a while,” Besola explains. “When he saw me at a party, he just lifted me up, my feet were off the air. He didn’t need to tell me that he loved or missed me but from what he did, I could feel that love.”

Besola tells gal-dem he can’t believe that the bubbly and adored little cousin is no longer here. “Chris was the life of the party. When he walked in, he was immediately the centre of attention. He was very comedic. He was always playing around with people. He had a really good sense of humour.”

Besola adds: “One thing about him is that he knew how to make people feel special. I think that’s a very important trait. Chris was the type of person to show and value that love.”

Kaba grew up in Croydon’s tight-knit Congolese community. “In childhood, Chris was a tough person, but he had a soft centre,” Besola says. “At gatherings and parties, he would always be found on the dance floor, always dancing. His parents loved him. That’s a given with most parents, but his parents absolutely adored him. You’re not supposed to have favourites, but you can tell Chris was the favourite.”

Kaba was to get married soon, and according to Besola, absolutely doted on his fiancé. “Chris was so in love. He was really soft with her, so tender. I knew he would be a good dad because he was a good family man, the way he treated his cousins and their children.”

To the people who knew Kaba, he was a talented, passionate artist and friend. A childhood friend, the artist Still Shadey, 26, from Croydon, says Kaba was more like a brother. “Chris was bold, someone in the room who would make you smile,” Shadey says. “He was smart, talented and had a bright sense of humour and character. Chris was an entertainer at heart. He would lift your mood, he was passionate, he was strong.”

“Chris loved his child, but just never got the chance to be a father”

Still Shadey

But just as with his death, Chris’ life as a young drill artist was politicised. He was part of MOBO-winning group ‘67’ who spoke of the resistance they faced from police, as drill was, and continues to be, dubbed a ‘dangerous’ genre. In 2018, Dimzy, part of 67, called out the police’s use of this genre as a scapegoat to pin the blame for rising crime in the capital. Even now, as Streatham MP Bell Ribeiro-Addy pointed out, Kaba’s past has been referenced unfairly in the reporting of his death.

For those who knew him well, Kaba was a leader in the community. “He knew who he was in a world where people don’t acknowledge or recognise that about themselves; he was honourable. It was inspiring to see someone his age have that sense of love for his people,” says Shadey. “His baby is going to come into this world not knowing Chris’ brightness, his talents, his joy. Chris loved his child, but just never got the chance to be a father.”

The police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Tony McDade two years ago exposed the severity of police brutality and the systemic racism of the justice system in the US. But the UK is not innocent either. At Kaba’s protest, signs also honour others whose lives were cut short at the hands of the police, including Sarah Reed, Jimmy Mubenga, Dalian Atkinson, who died due to the state’s mistreatment of people with mental illnesses, and the force’s overzealous use of heavy restraint.

‘An inherently racist institution’

It took the police watchdog almost two weeks to ask whether race was a factor in Kaba’s killing, while his loved ones question whether it was really the car the police were chasing, or a Black man at the wheel. When Black people are more likely to be surveilled, arrested and detained, it’s hard to separate racial discrimination from policing. It’s no wonder then, that the community has little trust in police.

“Policing is an inherently violent and racist institution,” says 4Front. Crucially, it’s not about a ‘few bad apples’ within the system, but an institutional problem, they say.

4Front and other campaigners say the reliance, funding and trust in policing in the UK should be reallocated, as we saw in the demands for abolishing the police following the killing of George Floyd.

“As long as policing institutions have resources, tools and powers, we will continue to see Black people treated as disposable by this system. We need to divest resources from policing and invest them into the kinds of infrastructure that can repair harm, provide opportunities for healing and the type of support required for those most impacted by violence and trauma.”

The 4Front spokesperson added: “Defunding the police is one solution to preventing the harm inflicted upon our communities. Defunding means preventing police from obtaining militarised equipment and instead reallocating funds to community-based services and alternatives that nurture healing rather than criminalising and murdering us. Defunding is about reducing their power and reinvesting into a world that no longer depends on the dehumanisation of Black people.”

On 21 September, Kaba’s parents were shown bodycam footage of the incident in a meeting with the Met Police commissioner, Sir Mark Rowley, and the IOPC director general Michale Lockwood. In a statement, his mother described the meeting as “hard, very hard… As I’ve said before, my heart is already broken. What I want is justice for my son and I want the truth.”

The fight to bring justice for Kaba is not over, with many more demonstrations planned in the future. And in the chants for justice and peace, his loved ones want Chris Kaba to be remembered as a son, brother, cousin, friend, partner and father-to-be.

An inquest into Kaba’s death will open on 4 October.

Follow the Justice for Chris Kaba campaign here.

Our groundbreaking journalism relies on the crucial support of a community of gal-dem members. We would not be able to continue to hold truth to power in this industry without them, and you can support us from £5 per month – less than a weekly coffee.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?