Last month Donald Trump lifted the ban which previously prohibited the remains of endangered animals from being imported to the US, and it seems not much has changed in the game of ‘trophy hunting’ since European men landed on the continent of Africa.

Once upon a time, ‘explorers’ and colonisers studied the land; they mapped it, catalogued various exotic species, set up institutes of African anthropology and tropical medicine, wrote extensively about the ‘savages’ of the land (and of course of the wild and wonderful animals they lived beside). As industrial technology developed, they traveled further into the ‘dark continent’, with their binoculars and guns close at hand. They were here to explore, to discover, to civilise.

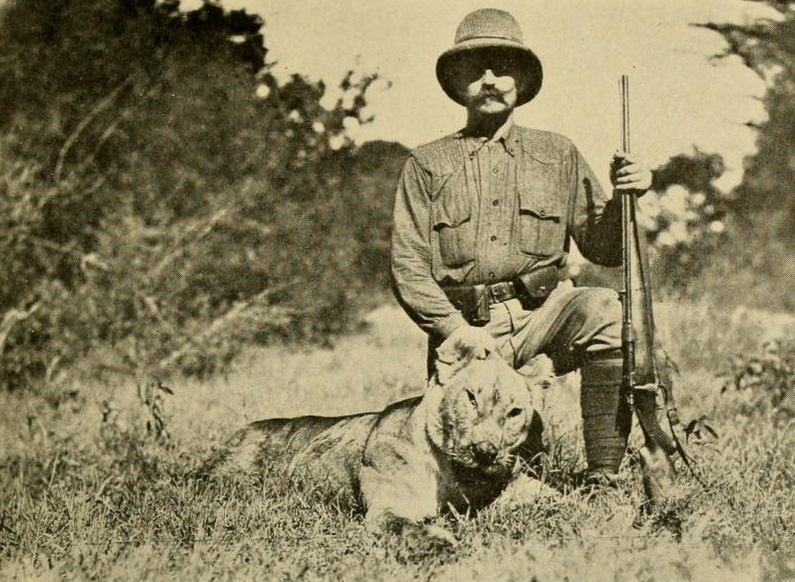

Soon, these ‘explorers’ began to kill man and beast alike. These trophies were stuffed, photographed, catalogued, and sent home to the “oohs” and “aahs” of the metropole. Some were displayed in museums, magazines and trade shows. Others were shipped off to historical universities or to the homes of the wealthy and powerful; in the former dissected and analysed, in the latter displayed with imperial pride. This was progress.

Trophy hunters relished in their experiences as men of the bush, they wrote extensively about the value of savage reconnection, of how killing an animal unleashed a carnal thirst for blood and the innate hunter instinct of man. Later, they retired to a country cottage home, had a cup of tea, and felt awash with pride as they gazed at the stuffed artifact of their experience as a savage man, ready to be shipped home to a more polished surrounding. Of course, they had black servants to clear up the dishes and stoke the fire.

Fast forward to 2016, and a report by the Humane Society of the US found that a key motivation for trophy hunting was that “hunters glamorise the killing of an animal so as to demonstrate virility, prowess, and dominance.” It’s a familiar image – people clad in khaki and other jungle attire squat by their ‘prey’ proudly, as if to recall the familiar “man vs. beast” battle of their imaginary predecessors.

But this story has never been about man vs. beast alone – it has been also a story of man vs. men. A story of a European man whose ego hunches and beams at the foreground of an image – whilst the background depicts a wild savannah open and ready for the conquering – a ‘no man’s land’ which, by the bang of a bullet, becomes a white man’s land.

Arguments for trophy hunting are often premised upon the high monetary value that the legal ‘industry’ brings to indigenous lands, and of how wages paid by hunters fund conservation initiatives in those countries. However, this is a massively decontextualised picture – it leaves out the fact that the impoverishment of those lands often stems from the very same countries from which ‘charitable’ trophy hunters come in the first place.

This narrative also glosses over the reality that conservation efforts are necessary in part because of ongoing conflicts between local populations and the wild – conflicts which are exacerbated by the fact that many of those local populations had been displaced from their ancestral lands by the appropriation of colonial land. Local populations are continually disenfranchsied by the ongoing disregard for their native economies, a toxic collusion between the ‘world’ (i.e. western-ruled) economy and local complicity and corruption – often trickling down from central government. The story goes that trophy hunters fund conservation efforts, but how can a ‘remedy’ be part and parcel of the disease itself?

Trophy hunting is not about man vs. beast, nor is it about a benevolent past-time. Trophy hunting is about the exploitation of a precious resource used to light the fires of egos that feel so far removed from their authentic humanity that they feel they must kill to gain some carnal essence that has long been lost in a society of empty comforts. It is a drain on the vital force of nature, downed in a gulp by the greedy throats of wealth and power.

This idea of the ‘benevolent’ western ‘explorer’ adding value to African property by their extradition thereof must be killed. There is no monetary value that can be ascribed to a precious resource that has dwindled so quickly since the ‘scramble for Africa’ began. 5-10 million African elephants existed in 1930. Less than 1% of that number remained in 1989. Those deaths have resulted in a large part from the combined evils of hunting and land displacement – legacies of colonialism which continue in the trophy hunting ‘industry’ we hear of today. We must wake up to the reality that the lives of our wildlife far outweigh any dollar figure in the hands of another greedy ‘tourist’.

Whether we like it or not, Africa is vulnerable. I speak from the perspective of a Kenyan, where the combined fault lines of an underfunded Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS), a kleptocratic government, a colonial power with abundant influence, and the creeping power of the pernicious Chinese poaching industry meet at a seismic junction which will shake the existence of our precious wildlife to the core. We cannot allow trophy hunters to gain more of a foothold because we simply will not live to see our elephants, rhinos and lions survive that.

In truth, trophy hunters are not, and never have been, benevolent. They are exploiters in every sense of the word, and if we continue to believe that something so precious as the lives of animals unique to an African ecosystem can be quantified with dollar and pound signs, we leave open yet another floodgate for the richness of the African continent to be drained, irreversibly. Conservation will not be bred from the bosom of further western ‘benevolent’ exploitation.

Trophy hunting bangs the drums to signal that Africa is, still, here for the taking. But what happens when we have nothing left?

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?