‘We’ve been here so long now – it’s all or nothing’: inside the Goldsmiths student occupation

Micha Frazer-Carroll

27 Apr 2019

Photography by Micha Frazer-Carroll

I’m eating veggie fajitas in Deptford Town Hall, with a group of students who look a bit like me. Most are also women and non-binary people of colour, barring one student’s snoozing newborn, who’s being passed around to a chorus of coos.

Today marks day 47 of Goldsmiths students’ occupation of the town hall, a key university building. But it’s someone’s birthday, so accordingly, our huge dinner table is decked out not just with Mexican food, but chips, Vietnamese rice paper rolls, vegan chicken nuggets and sausage rolls, an Oreo brownie traybake, sponge cake, and a large plate of vegan chocolate. It’s a suitably wholesome surprise party – after all there’s a spacious hall at our disposal, without having to pay so much as a penny of deposit.

But the celebration is somewhat of a silver lining. After all, we’re sat in the UK’s first occupation to be led by students of colour, but as it’s in response to widespread reports of racism on campus it seems uncomfortable to call this a positive landmark.

“Before coming here I was sold this whole package that Goldsmiths was this progressive, multicultural, radical place,” second year anthropology and media student Fiona Sim tells me. “When I came here, the racism was a shock to me…it was both covert and overt, in classrooms and in seminars.”

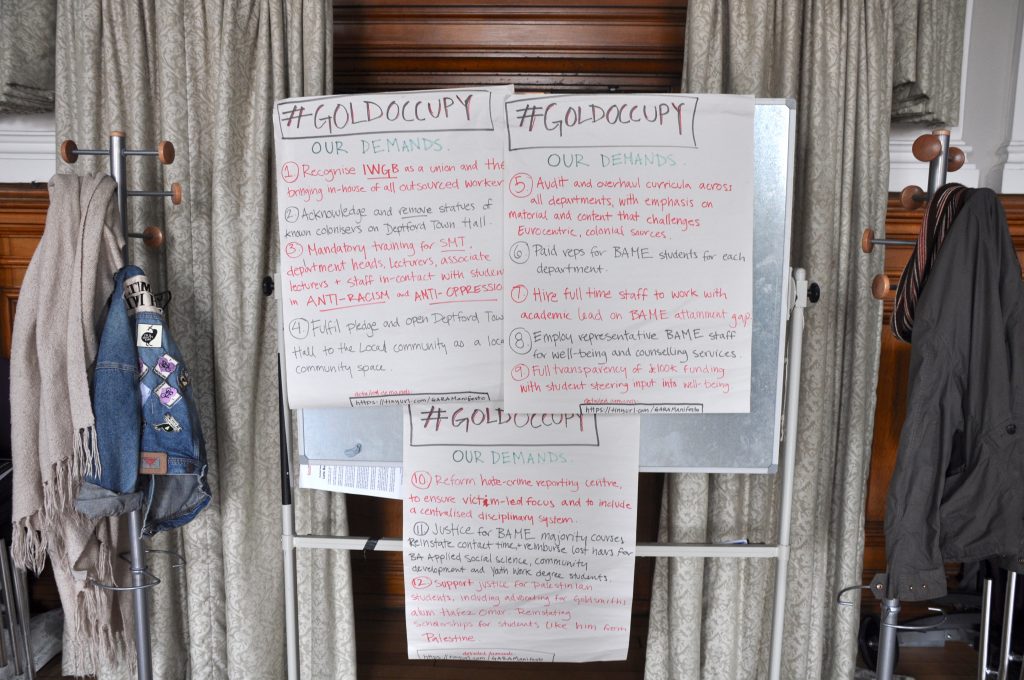

Occupations, a form of direct action, frequently come with a list of demands, and the students of colour leading at Goldsmiths haven’t pulled any punches. The group’s Google Doc manifesto embarks by stating “we resist the ironclad coloniality of Goldsmiths College, University of London that subjugates its BAME students, staff, and workers alike,” and goes on to outline a numbered list of six complex conditions on which they will end the occupation.

“Teachers go through years and years of training. Why can’t we ask lecturers to sit through one day for this?”

The demands surround the structural and cultural roots of racism on campus broadly; but Fiona explains that an alleged hate crime directed towards a candidate in the SU elections was the trigger for the occupation. “Racist slogans drawn on her posters, banners torn down. But the hate crime reporting centre didn’t want to do anything about it.”

After the allegations surrounding the elections, the group had decided to protest, demanding the release of surveillance footage so the person who vandalised the posters could be found. John Dior, a third year music computing student adds, with an eye roll that “the CCTV allegedly covered the whole of the cafeteria – except for the area where the poster was put up.”

What started as a protest became an occupation – and it was over these initial days that the group started to formulate specific demands. “We knew we to make it broader than just that isolated incident,” Fiona says. “There’s not a single student of colour you can talk to on campus who hasn’t had negative experiences in seminars, lectures, and day to day life.

“So we didn’t want a situation where they resolved that specific case and just patted themselves on the back thinking they’d ‘solved’ racism.”

But what creates a racist university environment in the first place? Fiona says they saw it as essential to look more broadly to the conditions that allowed alleged hate crimes to take place on campus. “Why do we not have mandatory training for all staff? At the very least, they should be knowledgeable of what racism is, what oppression is, and how it works.

“Teachers go through years and years of training. Why can’t we ask lecturers to sit through one day for this?”

Photography by Micha Frazer-Carroll

A number of the demands will look familiar to those who have followed conversations surrounding race on campus in recent years. The students have asked for four statues of “known colonisers and the slave ship owners” to be taken down from outside the town hall; an echo of the Rhodes Must Fall campaign that garnered public attention at the University of Cape Town, and later at Oxford University.

Another familiar concern, similar to those raised by Kings’ students last month, is the increasing surveillance of international students through technology. Fiona and John feel particularly apprehensive about the potential introduction of SEAtS software, which allows close digital tracking of student attendance, and can be used to deliver information to the Home Office. One condition of the general student visa is to meet a minimum attendance requirement, which can be as high as 80%. If students fail to meet attendance requirements, they could be threatened with deportation. SEAtS’ website describes its software as “visa compliance made easy”.

Fiona explains this is unfair, saying that international students, who are disproportionately students of colour, often stop attending classes when they’re struggling most. “They can come and sit in a classroom, but it doesn’t mean that they’re doing well, or that they’re not feeling isolated.”

“I was sold this package that Goldsmiths was this progressive, multicultural, radical place”

They also say efforts to monitor students’ experiences, using methods like NUS’ reporting tools, have also presented a bleak picture. “Looking at the testimony, there are so many experiences of people being told to go back home, being told they should be speaking English, being asked why they’re here.”

A spokesperson for Goldsmiths, University of London, told gal-dem last month: “We are proud of our diverse and inclusive community and prejudice of any kind has no place on our campus.”

But this doesn’t seem to match up to student testimony – Fiona says: “Black students have had to sit through seminar leaders literally reading out the n-word.”

But beyond students, the group are also concerned about the university’s security workers, who are majority-black. Improving their working conditions is thus one of their demands. “We know we can’t just be fighting for ourselves,” Fiona says.

“At the end of the day we are students who will come and go, but for many security, they’ve been here for 10, 20 years. It would be really arrogant of us to just care about our issues.”

Goldsmiths has a complex historical relationship with race. In 2016-17, 40% of students were BME, yet there is a 19% attainment gap between white and black students. The university also made headlines four years ago when student officer Bahar Mustafa was charged with “sending a threatening communication” after it was claimed she tweeted “#killallwhitemen”. She became the centre of a media storm and ultimately stepped down from her position at the students’ union. Despite denying the allegation, Bahar added: “I, as an ethnic minority woman, cannot be racist or sexist towards white men, because racism and sexism describe structures of privilege based on race and gender.”

The same issue of “reverse racism” is now a part of the occupiers’ manifesto, which states: “Any commitments to hate crime prevention and hate crime resolution must acknowledge the non-existence of reverse racism.”

“We’ve had to sit through seminar leaders reading out the n-word”

While the students wait for their demands to be met, Nishat, a first year sociologist, explains that they’ve repurposed the space and made themselves at home; since student occupations rarely go on this long, it’s no longer a temporary operation. A tall screen is set up at the end of the room,The Office beaming out from behind the tiered lecture seats across the vast, high-ceilinged, wood-panelled hall.

“We didn’t realise there was a huge projector in here for ages,” she says.

For relaxation there are cushions, blow-up beds, fairy lights and a home cinema in the main area. A separate wellbeing room is housed in a repurposed office down the hall. “We actually have an incredible number of Muslims in the occupation,” Nishat tells me, gesturing to the overlapping prayer mats in the corner. As well as a space for mindfulness, craft and reflection, it doubles as a prayer room for those who need it.

To me, it looks as though the group have carved out a space that meets the needs of students of colour that universities often fall short on. But John (who is black and non-binary but explains they’re generally read by others to be a black man), says that racism has unavoidably pervaded some parts of the occupation, and that the group have been mindful of how different members’ bodies are perceived since the beginning. “Early on we made the choice that people that would be identified as black men would not be at the forefront, or involved in direct demonstrations, because we saw it that security would often use that as a cause to escalate.

“I’m always going to be seen as a lot more suspicious,” they say, telling me that the way they’re seen can be summarised by one incident when they were laying out eggs for an occupation Easter egg hunt. “I had just started putting out Easter eggs when all of a sudden I turned around, stood up, and there was security all around me asking me what I was doing,” they laugh – it’s such a common microaggression it’s almost a cliché.

Photography by Micha Frazer-Carroll

Fiona adds that one member of staff confronted a group of students after a protest, following the group down the road and “aggressively” asking questions about their experiences of racism. “In the end she took one of our leaflets and ripped it up in front of us.”

Despite perceived hostility from university management, there has been support from members of the local community, and sabbatical officers and students from across the country too. One student mentions that they “popped in once and never left,” which makes everyone crack up for longer than the joke seems to warrant. I don’t get it.

They add: “I’m from UEA, by the way.”

This level of solidarity is understandable – most students of colour will relate to the alienation that can result from feeling structurally overlooked and marginalised within your institution. John tells me that their motivation for participating is political, but also intensely personal. “Out of my original freshers friendship group that I came to Goldsmiths with, I’m the only one who hasn’t dropped out or left studies because of the racist environment.

“I’m the only one out of my freshers’ friendship group who hasn’t dropped out”

“I’m the only one still here, still trying to graduate. It’s really sad coming in with a really amazing support network and just seeing it slowly whittle down until it’s only you left,” they add. “I want it to be easier for people after me. I don’t want anyone to go through what I’ve gone through.”

While the list of demands is extensive, Fiona explains that the group of occupiers are now in it for the long-haul. “The longer we’ve held out, the more demands they’ve slowly agreed to – like increasing the number of staff looking into the black attainment gap at the institution.”

Fiona’s stance is firm – until all of the occupiers’ demands are met, they will not be leaving the building. “We’ve been here for so long now, it’s all or nothing.”